Whence the giant panda?

Well our first poll is over and the majority of the five hundred and nine votes cast say that giant pandas are not bears: 28% yes, 62% no, and 10% dunno. I hate to say it, but the majority is wrong.

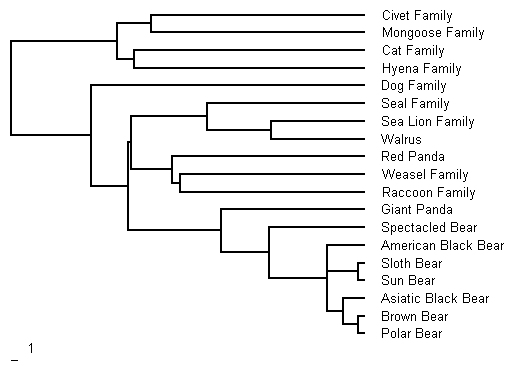

Giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) form the most basal branch of the bear family. The figure below shows the relationship of the bears to the rest of the extant order Carnivoria (Mammalia). It is the composite of two maximum parsimony phylogenies, Figures 1 and 8 of Bininda-Emonds et al. (1999), derived from data present in scientific literature. The scale of the tree is millions of years before present and was derived from data in Tables 2 and 9 of Bininda-Emonds et al. (1999).

The giant panda first appears in the fossil record about 3 million years ago during the Early Pleistocene. It had a wide distribution in the Pleistocene ranging from Myanmar to eastern China and as far north as Beijing (Schaller et al. 1985 p11 ). The giant panda lineage branched off from the other bears around 22 million years ago (Bininda-Emonds et al. 1999). It has been suggested that the giant panda is a descendent of Agriarctos, a “small, bearlike animal of the Ursavus lineage from the mid-Miocene in Europe” and the last surviving member of Ursidae subfamily, Agriotherinnae (Schaller et al. 1985 p229).

Although, there used to be a debate on whether the giant panda was more closely related to raccoons or to bears, multiple studies since the 1960s established its connection to the other bears. In 1869 the giant panda was first discovered by western zoologists and described as a new species of Ursus. However, the next year another zoologist claimed that the giant panda was not a bear but a relative of the red panda, which was at that time believed to be related to raccoons. In 1964, D. D. Davis published a comprehensive, comparative anatomical study that showed that the giant panda was a bear adapted for a particular food niche. After that, only a few zoologists held on to the idea that they two pandas were close relatives (Mayr 1986). Molecular studies beginning in the mid 1980s helped support the conclusion of anatomists and paleontologists.

O’Brien et al. (1985) used DNA-DNA hybridization, isozyme genetic distance, immunological distance, and karyotype evidence to estimate the relationships among the giant panda, red panda, and their supposed closest relatives. They concluded that the giant panda’s closest relative were the other bears.

Molecular and cytological methods specify the divergence of the giant panda from the ursid lineage of the carnivores at 15-25 Myr BP, whereas ancestors of the [red] panda emerge very near the time of the procyonid-ursid split.

O’Brien et al. 1985

Wayne et al. (1989) used similar methods to study a larger picture of carnivore evolution and similiarly concluding that the giant panda was a basal lineage of the bears.

The consensus treee indicates that between 30 and 40 M.Y.B.P. the progenitor of modern ussids and procyonids split into two lineages. Within 10 million years of that event the procyonid group split into Old World procyondis represented today by the red panda and the New World procyonids (for example, raccoons, coatis, olingos, kinkajous). Approximately 18-25 M.Y.B.P. the ancestor of the giant panda . . . diverged from the ursid line. The next divergence is between teh ursine bears and the spectacled bear . . . which occured between 12-15 M.Y.B.P. The lineages leading to the remaining species—the brown bear . . . the black bear . . . the sun bear . . . and the sloth bear . . . —first became distinct 5-7 M.Y.B.P.

Wayne et al. 1989

Goldman et al. (1989) used one- and two-dimensional protein electrophoresis to estimate the molecular distance among the eight species of bears, raccoon, and red panda.

The addition of two new data sets relating 289 proteins resolved by 2-D gels and 44 allozyme systems from living ursid species plus two procyonid species provides a corroborative basis for interpreting the evolutionary history of this group. The results were in topological agreement with each other and with previous phonetic trees derived using DNA hybridization, albumin immunological distance, and allozyme genetic distance (Sarich, 1973; O’Brien et al., 1985). The cumulative data suggestions an ancient ologocene split of the ursid and procyonid progenitors. Within then million years of that event, the red panda diverged from the lineage that lead to the raccoon. Modern procyonids consist of 19 distanct species, and all but the red panda are found in the New World (Nowak and Paradiso, 1983).

Within the ursid radiation, there are three primary divergence nodes that consistently appear. The earliest is the line that lead to the giant panda, the second lead to the spectacled bear, and the third is a polytypic divergence node with lead to the speciation of size species of usine bears. The divergence relationship among ursine bears was not resolved with any of the molecular data sets with the exception of the affirmation of the close affinity of the brown bear and the polar bear.

Goldman et al. 1989

Hashimoto et al. (1993) studied alpha- and beta-hemoglobin sequences from various carnivores using maximum likelihood. They also concluded that the giant panda’s closest relatives were the other bears.

And finally, in a recent study using DNA fingerprinting, Wan et al. (2003) conclude that the giant panda may have two subspecies, Quiling and Sichuan.

Based on the large genetic difference between the QLI [Quiling] and Sichuan populations, we hypothesized that the giant panda may have differentiated into two subspecies. Key morphometric measurements were taken from 37 adult skulls. . .. The results revealed very significant differences between the QLI and Sichuan populations, with 7 morphological parameters. The measurements indicate QLI giant pandas had smaller skulls than Sichuan individuals. The molecular and morphological evidence indicates that two subspecies of the giant panda have formed. . ..

Wan et al. 2003

- Bininda-Emonds ORP, Gittleman JL, and Purvis A (1999) Building large trees by combining phylogenetic information: a complete phylogeny of the extant Carnivora (Mammalia). Biological Reviews 74 pp143-175

- Goldman D, Giri PR, and O’Brien SJ (1989) Molecular genetic-distance estimates among the Ursidae as indicated by one- and two-dimensional protein electrophoresis. Evolution 43(2) pp282-295

- Hashimoto T, Otaka E, Adachi J, Muzuta K, and Hasegawa M (1993) The giant panda is close to a bear, judge by α- and β-hemoglobin sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution 36:282-289

- Mayr E (1986) Uncertainty in science: is the giant panda a bear or a raccoon? Nature 323 pp769-771

- O’Brien SJ, Nash WG, Wildt DE, Bush ME, and Benveniste RE (1985) A molecular solution to the riddle of the giant panda’s phylogeny. Nature 317 pp140-144

- Schaller GB, Jinchu H, Wenshi P, and Jing Z (1985) The Giant Pandas of Wolong. The University of Chicago Press.

- Wan QH, Fang SG, Wu H, and Fujihara T (2003) Genetic differentiation and subspecies development of the giant panda as revealed by DNA fingerprinting. Electrophoresis 24 pp1353-1259

- Wayne RK, Benveniste RE, Janczewski DN, and O’Brien SJ (1989) Molecular and biochemical evolution of the Carnivora. in Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution. ed. Gittleman JL. Cornell University Press