Better Living Through Evolution, pt. 1: Cleaning up a mess/upending the "scientific key" of ID.

This is the first in an ongoing series about recent discoveries and commentaries concerning aspects of evolution that affect our everyday lives. On the one hand, it’s a fun way to showcase some of the recent goings-on in the literature, and on the other, it’s a way to rebut the occasional creationist claim that evolution isn’t important to biology or to science at large. That assertion is false, and would be irrelevant even if true, but in my opinion (and I suspect this is true of most of us here), the aspects of evolution that affect our day-to-day lives are the most fascinating.

Consider the existence of man-made pollutants. Since the advent of modern chemistry, humans have found ways of making new and useful chemicals that can’t be found in nature. Unfortunately, part of what makes a chemical useful is its ability to resist breaking-down. And if it happens that such a chemical gets produced in huge quantities, and that some of this quantity manages to make its way out into our environment, it can be quite a hazard to human and environmental health. The resistance to degradation becomes a part of the problem, because these chemicals can accumulate over many years to the point where they become toxic. It’s therefore important for us to understand methods by which these compounds can be eliminated.

Fortunately, our bacterial friends have evolved ways of dealing with many of the persistent pollutants that have been dumped into the environment. In a just published review in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Lawrence Wackett of the University of Minnesota describes some of the enzymes that microbes have evolved to digest these man-made chemicals. Unlike enzymes that evolved gillions of years ago, many of which have histories that are impossible to reconstruct, these enzymes show signs of having evolved quite recently. Wackett notes:

Another lesson being learned from biodegradation studies is that functionally significant enzyme evolution occurs on shorter time scales than previously appreciated; weeks, months and years rather than eons.

It’s precisely because these xenobiotic compounds did not exist before humans started making them that we have strong reason to believe that these are recently evolved abilities. And that makes them excellent case studies for how such evolution occurs.

PCP Degradation.

(There are several enzymes discussed in the review; I choose to talk about only one of them, so read the article to get the low-down on the rest.)

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) is a good example of a nasty environmental pollutant. First introduced as a wood preservative in the 1930’s, PCP is a major pollutant of soil and groundwater. It’s therefore quite fortunate that a pathway for breaking-down PCP has evolved in certain bacteria, and it appears to have done so in a mere matter of decades. This opens up the possibility of using bacteria to clean PCP contaminated soils, a process known as bioremediation (see this successful case study, for example).

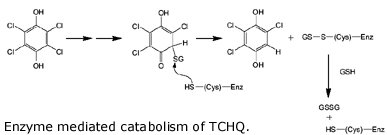

Wackett describes the evolution of one of the enzymes involved in breaking down PCP, tetrachlorohydroquinone (TCHQ) dehalogenase. This enzyme catalyzes the second step in PCP biodegradation, a two-step reductive dehalogenation of TCHQ to 2,6 dichlorohydroquinone (see the figure, but don’t feel obligated to make sense of it).

So where did the enzyme come from? As it turns out, TCHQ dehalogenase is similar in sequence to enzymes known as maleylacetate isomerases, which function in the breakdown of the amino acids tryrosine and phenylalanine. And lo and behold, TCHQ dehalogenase has some vestigial maleylacetate isomerase activity, an activity which is totally unnecessary because the bacterium can already catalyze this reaction from other enzymes. So the TCHQ dehalogenase appears to be adapted from an ancestral enzyme that had an altogether different purpose, yet it still maintains some of that ancestral activity. What other clues do we have for its recent emergence? Wackett points out that the enzyme suffers from severe substrate inhibition, which hinders the enzyme’s activity. Anandarajah and coworkers have interpreted this as evidence for its recent emergence:

Although we cannot definitively answer this question [when the enzyme evolved], the severe substrate inhibition of TCHQ dehalogenase by the aromatic substrate suggests that the enzyme is “immature”. We suspect that the substrate inhibition is a consequence of the recruitment of an enzyme with a single glutathione binding site to catalyze a reaction requiring 2 equiv of glutathione. This “design flaw” has apparently not been remedied, either because of inadequate time or because of the absence of the necessary selective pressure. Indeed, there is currently no selective pressure to improve the performance of this enzyme, since the rate-limiting step for the pathway appears to be the initial conversion of PCP to TCHQ. This design flaw is consistent with, but does not prove, a recent divergence of MAA isomerase and TCHQ dehalogenase.

On top of all of that, the TCHQ gene is constitutively expressed, meaning that the gene is turned “on” all the time. This is expected if the gene is recently evolved, because it would have been stripped of its ancestral regulatory apparatus. Tightly controlled regulation is undoubtedly a highly evolved feature, something that we don’t expect of newly evolved genes. Instead, the enzyme is simply produced at a constant pace, a wasteful process that nonetheless ensures that it will be present when needed.

An additional fact worth pointing out is that PCP degradation is “irreducibly complex” (IC), because each of three enzymes must be present and functioning for the degradation pathway to work. Yet in spite of the claims of Behe, who says that IC can’t evolve, the PCP degradation pathway appears to have evolved in a relatively short period of time, and we have a perfectly good model for how it happened. However, the evolution of the entire pathway is beyond the scope of Wackett’s review, which focuses only on individual enzymes, and so I won’t go into details. They’ll be more on this in the future though.

Enzyme Promiscuity.

The ability for new activities to evolve from old ones is an important concept, because it’s unlikely for useful enzymes to evolve from scratch, at least in such a short period of time. What is far more likely, and quite ubiquitous in evolution, is for new enzymes to be adapted from those that perform related functions. As Wackett notes, enzyme “promiscuity” offers substantial opportunities for the evolution of novel catalytic abilities. Enzymes tend to be well adapted for catalyzing specific reactions with specific substrates. Yet almost invariably, they are able to work on substrates that are chemically related, though usually with much less efficiency. And they can oftentimes perform different but related activities on those substrates. So if bacteria come across some new food source, or a toxic compound that threatens them, there’s an excellent chance that somewhere within their enzymatic repertoire, they already have the ability (just barely) to break down that compound. And if they don’t already have it, the steady drumbeat of mutation, somewhere within a large population, is likely to alter an existing enzyme so that it can act weakly upon the compound. And that’s all that natural selection needs to get started. If the compound in question is abundant enough, the ability to efficiently break it down will quickly evolve. Over many generations, natural selection will tweak any enzyme that can weakly act upon the compound to the point where the enzyme is highly specific for that compound.

New Abilities, New Information.

The evolution of a new enzyme activity from an old one may involve a compromise of sorts, if an older activity is weakened, or it may involve jettisoning the old activity altogether, possibly making the bacteria dependant on their new food source. But if the gene in question duplicates, then the old activity can be maintained while highly specific activity towards the new compound evolves. (With most biodegradation genes, it appears that the new gene gets encoded on a plasmid and spreads about by lateral transfer, a condition which does not require the ancestral gene to be lost or diminished.) In this manner, organisms become more complex over time and gain new “information” if you will. Think of it this way: An organism has a gene that encodes a protein with ability A (say it’s an enzyme, which catalyzes a specific reaction). Then the gene for A duplicates, so that you have two genes which have A as the function. One of the duplicates maintains its old function, but the other one gets selected for a new function. It can do this because it’s “promiscuous”, and can weakly catalyze a reaction that provides a useful result, like the breakdown of a toxic compound. Natural selection fine-tunes the new gene until it’s highly specific for its new activity, and only weakly (or maybe not at all) able to do its old job. Now you have both function A and function B, being carried out by two genes instead of one. (Note that the gene can duplicate at any time, either before or after it begins to evolve specificity towards the new function.)

There are mathematical meanings of “information” that other contributors here have talked about, but most of us intuitively think about information as being synonymous with functional complexity. And indeed, most creationists never bother to define what they mean by “information”, so the intuitive meaning is what we have to go by most of the time. If you go from A to A+ B, that’s clearly an increase in information, at least if “information” is to have any biological meaning.

This is precisely the kind of thing that ID/creationists have repeatedly claimed can’t happen, yet we see it happening right in front of us. Philip Johnson has quite foolishly claimed that this is the central axis upon which the entire ID movement rotates:

You have said there is no natural explanation for the rise of genetic information. How important is that question in the debate?

PJ: The Wedge of Truth is all about those issues. The scientific key is, “No natural processes create genetic information.” As soon as we get that out, there’s only one way the debate can go because Darwinists aren’t going to come up with a mechanism. They’ll start out talking about the peppered moth, and when that self-destructs, then they’ll say, “Oh, self-organizing systems, or the fourth law of thermodynamics,” and other nonsense, which is just covering up ignorance.

I somehow doubt that Johnson will admit that the “scientific key” of ID is completely bogus, but there you have it. It’s a good thing too, or we’d have a much bigger mess to clean up.

- Wackett LP. “Evolution of enzymes for the metabolism of new chemical inputs into the environment.” JBC, 2004 Jun 8 [in press]

- Anandarajah K, et al. “Recruitment of a double bond isomerase to serve as a reductive dehalogenase during biodegradation of pentachlorophenol.” Biochemistry. 2000 May 9;39(18):5303-11.