The Last Universal Common Ancestor

by Mike Syvanen

[Dr. Michael Syvanen is a professor studying molecular genetics in the Department of Medical Microbiology at the University of California, Davis, and has been an advocate since the early-80s of an idea that has gained considerable support over the last few years - that much evolution is not tree-shaped, but net-shaped. That is, that genes cross taxonomic lineages. Since many attacks on evolution claim we should “teach the controversy”, we at Panda’s Thumb thought it might be nice to present an *actual* controversy in science. Discussion is welcomed. Here, at least.]

It has been over 30 years since the suggestion that horizontal gene transfer (HGT) may have been a factor in the evolution of life entered the literature. Initially these speculations were based on discoveries made in medical microbiology; namely that genes for resistance to antibiotics were found to move from one bacterial pathogen to another. This discovery was so unexpected and contrary to accepted genetic principles that though announced in Japan in 1959 (1,2) it was not generally recognized in the west for another decade. Speculations that HGT may have been a bigger factor in the evolution of life was inviting because it offered broad explanations for a variety of biological phenomena that have interested and puzzled biologist for over the last century and a half. These were problems that had been raised by botanists that have puzzled over the evolution of green plants (3) as well as by paleontologists that recorded macroevolutionary trends (4) in the fossil record that were often difficult to reconcile with the New Synthesis that merged Darwin’s thinking with Mendelian genetics. However, outside of the field of bacteriology this exercise did not really attract that much attention until the late 1990s at which time there was a major influx of data indicating that HGT had been very pervasive in early life. Namely, complete genome sequences began to appear. Simple examination of these sequences showed beyond any doubt that horizontal gene transfer was indeed a major factor in the evolution of modern bacterial, Archael and Eukaryotic genomes.

As an example for how profound the notion of HGT has changed our thinking concerns the notion of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). This is an idea that was central to the hypothesis that life shared common ancestors. Though the idea of common ancestry remains valid (indeed evidence for common ancestry is everywhere in the sequence of our genes) there is no longer a need to postulate that all life evolved from a single last universal common ancestor. Rather, we can entertain common descent from multiple ancestors.

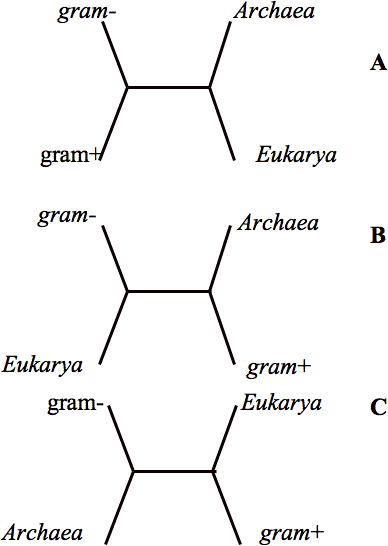

The notion that all life passed through a single interbreeding bottleneck is still probably believed to be true by most people who think about this problem. The reason is simple. There are many genes involved in information processing (i.e. DNA replication, RNA transcription and protein synthesis) whose molecular homologs are found in all three major domains of life. Furthermore, when the sequences of these genes are submitted to phylogenetic analysis they more or less support the following relationship – the Archaea and Eukaryotes define a branch to the exclusion of a bacterial branch and a single line links both. Figure 1a shows this relationship. The figure shows an unrooted tree with four of life’s major groups. These are the Archaea, the Eukaryotes and two of the major groups of bacteria. The Archael/Eukaryote branch, by definition, implies the existence of a common ancestor for these two groups and further we can infer that a point on the line leading to the bacterial branch that represents the last common ancestor of all life. Thus we can say there is empirical support for the existence of the last common ancestor. I mentioned above that this scenario is more or less supported by the informational genes. The striking finding is that other genes common to the three major kingdoms frequently show exceptions to these relationships.

When it comes to the genes for energy metabolism Eukaryotes and gram-negative bacteria are usually more closely related to one another than they are to the Archaea and other bacteria (as in Fig 1B). These genes are thought to have become associated with the Eukaryotic cell through the endosymbiote that eventually gave rise to the mitochondrion (5,6,7). In green plants we can also trace the ancestry of many genes involved in carbon fixation, photosynthesis as well as other metabolic processes to cyanobacteria, the endosymbiote host that gave rise to the chloroplast. For many of the biosynthetic pathways the relevant genes yield even more complex relationships. Thus we have arrived at the current situation that is accepted by most – there remain a few genes (almost all associated with the most basic genetic informational processing) that reflect an evolutionary history that goes back to some very primitive LUCA, but that superimposed over the remnants of that primitive ancestor in modern genomes are numerous examples of subsequent horizontal gene transfer events.

The above is a good model and it requires good reasons to reject it. To begin, not all of the informational molecular homologues support the simple phylogenetic pattern outlined above. Even here there are some exceptions. These exceptions have been dealt with in one of two ways – first in some cases it can be argued that there is insufficient amount of sequence to rigorously support the true branch relationships (i.e. sequence noise or homoplasy is hiding the true pattern) or alternatively, these are informational genes that also have been involved in HGT events. Though some of the cases are still open to debate there are a number of cases where it is simplest to conclude that some of the informational genes have been involved in HGT events, this is especially true for some of the amino acid-tRNA charging enzymes (8); these enzymes are intimately involved in translating the genetic and hence are central to information processing. Once we reach this point then it is no longer possible to argue that biochemically complex processes such as protein synthesis are too complicated to have their genes being involved in HGT events; a position that was held at least up until 1998. In fact Woese (9) suggested there existed in the very primitive cells a less functionally constrained protein synthesis machinery that permitted some HGT events of these components thereby accounting for the few exceptions. In this formulation a LUCA at least implicitly remains in the model. But evidence for the LUCA is greatly reduced, at least with respect to the number of genes found in modern genomes that can be directly traced back to the LUCA via exclusive vertical evolution. In 1982 it was automatic to assume that because a biochemical process was found in all of modern life, than that process must represent evidence for the one interbreeding population of the LUCA. Now we know that many of the universal biochemical processes have moved horizontally multiple times. Thus today we have a greatly truncated LUCA from what we believed just a decade ago.

When speculating on the nature of the LUCA it is generally accepted that it must have contained the modern universal genetic code since that is a feature shared by all life. However, even if we accept the existence of this LUCA there are a variety of reasons to believe that the LUCA itself was the product of an evolutionary process that employed horizontal transfer events; this is so especially with respect to the evolution of the genetic code. It is very difficult to see how the modern genetic code could have evolved in a sequential fashion; rather the code must have evolved on separate occasions and become fused into single lineages. This problem is illustrated by considering the case of lysine-tRNA charging enzyme genes found in modern life. All life has two different completely nonhomologous enzymes. If the modern genetic code evolved in a sequential fashion, then we would have to imagine a situation where a lineage that carried one of the two enzymes evolved the second. The raises the question: what selective pressure could possibly to account for the emergence of this second enzyme when it already has one? It is much simpler to believe that the lysine enzyme evolved independently in two different lineages, which then fused to give rise to the ancestor of modern life. This is not a radical idea. Of course, if HGT is common to life after the time of LUCA then it seems not unreasonable to assume that it was common to life before the LUCA. At this point we come to the following model for evolution of life if we try to preserve the LUCA. We have multiple lineages of pre-LUCA life that are linked together by HGT events into a netted or reticulate evolutionary pattern. This leads to the LUCA. The LUCA diversifies into its many modern lineages and then these lineages are again reticulated. We then end up with a topological model that looks like an hourglass. Namely a net above that bottlenecks to the LUCA which then diversifies and yields a net below. At this point the principle of parsimony should kick in. Why encumber our model with this bottleneck. It is not only no longer necessary but is now an exceptional assumption.

There is another reason that we should jettison the LUCA. This has to do with the finding that many of the universal genes including a number that make up the genetic code, are younger than are the major kingdoms of life. That is we can be reasonably sure that life forms resembling Archaea, bacteria and some kind of primitive Eukaryote existed before 1.5 and likely before 2 billion years ago. However, parts of the genetic code are younger than that. (see papers 8 and 9 at ref 11 for the documentation). The simplest explanation is the genetic code continued to evolve after modern life diversified. If so, then the only reasonable explanation for this is that these younger members of the genetic code must have achieved their current modern and universal distribution via HGT events. Once we accept that something as complex as the genetic code can evolve and spread by HGT events, it strongly suggests that a gene encoding any function could also.

There are deep ideological reasons for believing in a LUCA that explain the reluctance of many to abandon it. In fact this reason is built directly into the most basic model of modern biology, i.e. the tree of life. The only figure in Darwin’s “Origin of Species” happens to be a tree that inevitably maps back to a single trunk. Indeed the algorithms used in phylogenetic analysis can only find a single trunk, which, of course, is how they are designed. All practicing biologists are aware of the limitations of phylogenetic modeling with its built in assumptions, but nevertheless these assumptions do cause confusion. For example, let me pose a question and ask how often there was confusion when thinking about mitochondrial eve? Isn’t it a common misperception to think at some point that all of human life could be mapped back to a single woman? When in fact all we can say is that the only surviving remnant of that distant ancestor is her mitochondrial genome, and it is extremely unlikely that any of her other genes survive in any human populations. Because of the phenomena of sexual reproduction and recombination we share genes with multiple ancestors with no need to hypothesize any individual ancestor from whom we have descended. The same reasoning should apply to the evolution of all life; because of the phenomena of horizontal gene transfer we share genes with multiple ancestors with no need to hypothesize individual species from whom we have descended (10).

Michael Syvanen

UCDavis

June 23, 2005

-

Ochiai, K., Yamanaka, T Kimura K and Sawada, O (1959) Inheritance of drug resistance (and its tranfer) between Shigella strains and Between Shigella and E.coli strains. Hihon Iji Shimpor 1861: 34 (in Japanese).

-

AKIBA T, KOYAMA K, ISHIKI Y, KIMURA S, FUKUSHIMA T. On the mechanism of the development of multiple-drug-resistant clones of Shigella. Jpn J Microbiol. 1960 Apr;4:219-27.

-

Went FW 1971 Parallel Evoluion Taxon 20:197-226

-

Reanney D 1976 Extrachromosomal elements as possible agents of adaptation and development. Bacteriol Rev. 40:552-90

-

Golding GB, Gupta RS. 1995 Protein-based phylogenies support a chimeric origin for the eukaryotic genome. Mol Biol Evol. 12:1-6.

-

Gogarten JP, Doolittle WF, Lawrence JG 2002 Prokaryotic evolution in light of gene transfer. Mol Biol Evol. 19:2226-38.

-

Doolittle WF. 1999 Lateral genomics. Trends Cell Biol. 9:M5-8.

-

Brown JR, Doolittle WF. 1999 Gene descent, duplication, and horizontal transfer in the evolution of glutamyl- and glutaminyl-tRNA synthetases. J Mol Evol. 49:485-95.

-

Woese C. (1998) The universal ancestor.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95:6854-9.

-

Zhaxybayeva O, Gogarten JP 2004 Cladogenesis, coalescence and the evolution of the three domains of life. Trends Genet. 20:291.

-

This site has a number of HGT papers in .pdf by the author : (http://www.vme.net/hgt/)