Now that's a stretch

The Discovery Institute’s Casey Luskin is all atwitter about a new web article from German creationist Wolf-Ekkehard Lönnig [1] about how the giraffe is some kind of massive problem for evolution. Major planks [2] include the alleged lack of transitional fossils between the different fossil giraffe genera (never mind that creationists elsewhere typically accept that the differences between mammalian genera are small, and put the “created kind” or “basic type” at a higher taxonomic level), some confusion about whether one of the giraffe vertebrae is cervical or thoracic or something in between (note to creationists: read about homeotic shifts), and the allegation that there is no evidence for a feeding advantage for tall giraffes, relying on the fact that male giraffes are taller than female giraffes and a 1996 paper in American Naturalist (Simmons & Scheepers 1996, “Winning by a Neck: Sexual Selection in the Evolution of Giraffe”) that attempted to buck conventional wisdom and suggest that sexual selection was the cause of long necks in giraffes.

Sadly, the last plank is particularly bogus, since it completely ignores and displays no knowledge of a massively relevant and quite brilliant paper, published just back in January 2007 in American Naturalist, that constitutes an experimental demonstration of the relative feeding advantage of giraffe height:

Elissa Z. Cameron and Johan T. du Toit (2007). “Winning by a Neck: Tall Giraffes Avoid Competing with Shorter Browsers.” The American Naturalist, 169, 130–135. DOI: 10.1086/509940

Abstract With their vertically elongated body form, giraffes generally feed above the level of other browsers within the savanna browsing guild, despite having access to foliage at lower levels. They ingest more leaf mass per bite when foraging high in the tree, perhaps because smaller, more selective browsers deplete shoots at lower levels or because trees differentially allocate resources to promote shoot growth in the upper canopy. We erected exclosures around individual Acacia nigrescens trees in the greater Kruger ecosystem, South Africa. After a complete growing season, we found no differences in leaf biomass per shoot across height zones in excluded trees but significant differences in control trees. We conclude that giraffes preferentially browse at high levels in the canopy to avoid competition with smaller browsers. Our findings are analogous with those from studies of grazing guilds and demonstrate that resource partitioning can be driven by competition when smaller foragers displace larger foragers from shared resources. This provides the first experimental support for the classic evolutionary hypothesis that vertical elongation of the giraffe body is an outcome of competition within the browsing ungulate guild.

The beautiful thing about this paper is how simple the experimental design is. Basically:

Step 1. Find a game reserve with giraffes in it (in this case, Lion Sands Game Reserve in South Africa, near Kruger National Park)

Step 2. Build some browser-proof 2.2 meter-high fences around some tall acacia trees (giraffes can browse up around 4 meters, for obvious reasons). Wait through two growing seasons.

Step 2.5. Fix the fences occasionally when elephants come by and smash them in a malicious attempt to spoil your research project.

Step 3. Cut off some branches at various heights and measure the amount of leafy biomass. Do the same with some unfenced control trees. Compare.

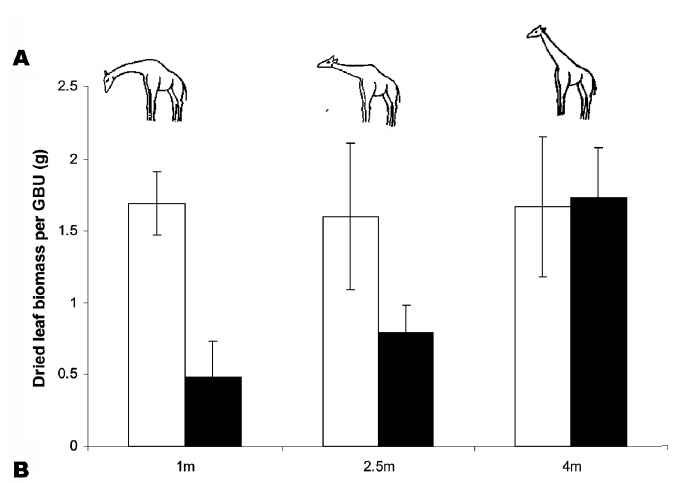

Here is one of the figures from the paper. Note: a “GBU” is a “Giraffe Browsing Unit”, an overly technical term for “giraffe bite.” So this chart is showing how much leaf biomass is available per bite for the giraffes, at 1 m, 2.5 m, and 4 m.

Open bars are for the fenced trees, black bars for the unfenced control trees. You can see that the unfenced trees are severely denuded of leafy biomass at the low elevations, being heavily browsed by numerous critters. Giraffes, on the other hand, avoid this competition. Conclusion:

Despite popular acceptance that giraffes have long necks because of foraging competition during their evolution, no previous studies have experimentally investigated foraging competition between giraffes and smaller browsers. Simmons and Scheepers (1996) argued that there was little evidence that giraffes forage high in the canopy because of competition and suggested sexual selection as an alternate hypothesis. However, Woolnough and du Toit (2001) showed that giraffes achieve a bite-size advantage by feeding higher in the tree, and now we show that this is explained by the avoidance of competition with smaller browsers. While not resolving the controversy, our study provides the first experimental evidence that the giraffe’s extremely elongated body form is naturally selected in response to competition from smaller browsing species.

As the paper notes, this has always seemed pretty “obvious” to most people – especially if you have been to Africa and seen all the large herbivores, browsers and grazers of different shapes and sizes, living on one landscape by dividing up the food resource in minute ways (in fact, I noted that it was pretty obvious back in this 2005 PT post). But sometimes it’s nice to experimentally test the obvious – especially when creationists are going around denying it.

Notes

[1] Yep, he’s apparently pretty clearly a traditional creationist of the Jehovah’s Witness variety. He appeared in the German video Is the Bible Right After all? The theory of evolution lacks evidence. See links 1, 2, 3, 4.

[2] Amongst a large about of debris in the form of creationist ranting-n-raving about unrelated issues.