Bards, Poets, and Cliques

Humans have a unique form of complex communication called language. While some academics have argued that language is a purely cultural invention—Humans used their brilliant brains to reason that language was the best way to communicate.—there is ample evidence that language is a biological adaptation that evolved after our ancestors split from the ancestors of chimpanzees. For example, the face, mouth, and throat contain adaptations for the physical production of spoken language. Children acquire language through an innate ability, not using their higher reasoning skills. And regions of the brain have been shown to be critical locations for cognition specifically associated with language.

As a complex adaptation, there must be some genes underlying our language ability. However, the evolutionary dynamics of language-associated genes is poorly understood. Earlier this year, I published some research that I hope will help fill this gap. (I’ve been working on this research off and on for nearly 10 years.) The paper is entitled “Bards, Poets, and Cliques: Frequency-Dependent Selection and the Evolution of Language Genes” and appeared in the Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. The journal is offering free access this month, so you can download the paper for free.

As a complex adaptation, language did not miraculously evolve all at once. As the saying goes, natura non facit saltum (nature does not do “poof”). Likely the communication ability of our ancestors passed through several stages eventually producing moden language ability. Some well studied transitions are the origin of combinatoric language from holistic communication and the replacement of hand gestures with vocal communication.

Now imagine that you have a human population that contains two different language phenotypes. “Bards” have the ancestral phenotype, and “Poets” have a new phenotype that is potentially more efficient and fitter.—Two Poets interacting have a higher fitness than two Bards.—This increase in fitness can come from the ability of poets to confer more information to one another, communicate more accurately, or many other things. Note, we are talking about biological differences in language faculty, not cultural differences like whether Bards speak French and Poets speak Cajun.

However, because Poets are due to a recent mutation, they are initially rare in the population and mostly interact with Bards. Thus whether Poets are initially selected for depends on how well they can communicate with Bards, not on the potential to be really fit when communicating amongst themselves. This system is an example of positive frequency-dependent selection.

Now it turns out that if there is any communication problem between Poets and Bards, then Poets will be selected against when rare and cannot “invade” the population. Thus it would seem impossible for our language ability to have evolved to be as complex as it is, and some recent researchers have argued that language is a cultural innovation based on this result. While creationists would just give up, declare science over, and announce “goddidit”—“What good is half a language?”—science marches on.

The actual problem faced by novel language alleles is that their frequency must reach a threshold, above which selection will sweep them to fixation. This threshold is \(1-\sqrt{\frac{1+c}{1+2c}}\) where c measures the relative difficulty that Bards and Poets have in communicating with one another, and the gene for Poets is assumed to be dominant. While selection directed at this trait is unable to increase the frequency of novel alleles above this threshold, genetic drift operating in a small tribe can do it over several generations. Once the threshold is passed, selection favoring the abilities of Poets will cause them to fix in the tribe. This tribe can then act as a source for the migration of Poets to other tribes. However, Poets migrating to new tribes would still become rare again and thus selected against. Thus, higher level events like tribe splitting or war are needed to explain the spread of Poets through humanity.

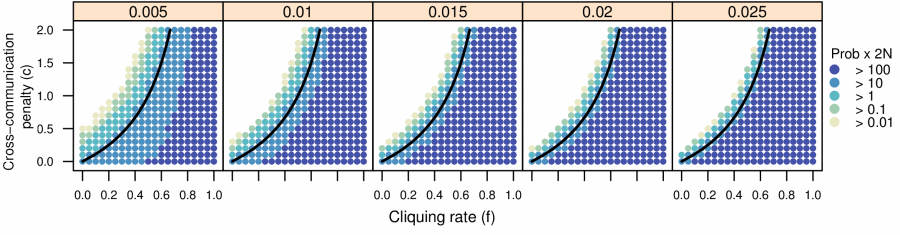

However, I show in my paper that the threshold problem is solved if individuals form language-based cliques.—Given how ubiquitously we form cliques, it is reasonable to assume that our ancestors also could form cliques.—In this formation, cliques encourage the interaction of Poets with Poets, reducing or eliminating the penalty that they encounter when rare. If f measures the rate at which Poets chose to interact with Poets and Bards with Bards, then the threshold becomes \(1-\sqrt{\frac{1+(1-f)c}{(1-f)(1+2c)}}\) which decreases as f increases. The threshold disappears completely when \(f \ge \frac{c}{1+c}\).

If cliques are common, then novel language-associated alleles can sweep through a population and improve the language faculty of humans. This is shown via simulation in the figure below. Clearly, the origin of language ability can be sufficiently explained by Darwinian processes operating on genetic diversity in a finite population of human ancestors.

Note that this model is applicable to social interactions beyond language as long as the fitness scheme is similar.