Meyer on Medved: the blind leading the blind

So, Stephen Meyer is allegedly going to “respond” to critics of Darwin’s Doubt this afternoon on the Medved show (Medved is a DI fellow, this particular show is being broadcast from inside the Discovery Institute). They are even inviting critics to call in – it’s your very own chance to rebut Meyer’s dozens of overlapping errors and admissions with a single question or statement, and with the Discovery Institute controlling the microphone! What a deal!

Over here in real science, we mostly try to address complex scientific topics through writing and analysis. And the critics have done quite a bit of that, although you’d never know it from reading the Discovery Institute blog, where David “spin til it hurts” Klinghoffer has pushed the rhetoric-to-truth ratio to heights not seen since the Kitzmiller days.

Klinghoffer’s constant refrain is that the critics aren’t addressing Meyer’s arguments. Well, let’s make a little list, shall we? It will be convenient as a checklist for anyone who listens to the Medved show today.

Major criticisms of Darwin’s Doubt by informed critics:

1. Meyer’s book, which is supposed to be about the Cambrian Explosion, gets the Cambrian Explosion fossil record wrong. The real fossil record is:

Ediacaran fauna in the Precambrian

Before the beginning of the Cambrian, we see then bilaterian worm tracks that gradually increase in diversity

In the latest few million years of the Precambrian, we observe Cloudina and other minute and very simple “small shelly” fossils

For about 20 million years, throughout the earliest part of the Cambrian, we see the “small shelly” fossil faunas gradually increase in diversity

Only after all of this do we reach the “main pulse” of the Cambrian Explosion. But even here, the representatives of the “phyla” mostly stem taxa, meaning that they lack some of the key characters found in the extant crown groups, and many of them exhibiting character suites “transitional” between the crown groups

Throughout the later Cambrian and on into the Ordovician, we have gradual takeover of faunas by the earliest members of what end up as the living crown groups, and further evolution of new bodyplans in the Ordovician for some groups

As Graham Budd writes in Budd 2003:

CONCLUSIONS

The combination of important refinements in the treatment of the systematics of Cambrian fossils, and in our understanding of Cambrian stratigraphy is leading to a more precise view of the Cambrian explosion. Phyla do not appear in a sudden jumble, implying an appearance in the fossil record induced by some external influence (e.g., a rise in atmospheric oxygen levels) that allowed a standing diversity already present to be manifested in the record. Rather, the impression rather is of a rapid, but nevertheless resolvable and orderly appearance, starting with the earliest skeletal forms such as Cloudina that are reasonably assignable to a diploblast grade (i.e., stem- or crown-group cnidarians or basal stem-group bilaterians). These are followed by taxa that lie in basal positions within bilaterian clades, and (in general) considerably later by representatives of the crown-groups of phyla. Revisions to the Cambrian time-scale allow a moderately long period of time, some tens of millions of years, between the first likely bilaterian trace fossils, and the general appearance of crown-group members of the phyla.

However, however, because of poor research, or a tendency to ignore inconvenient facts, or both, all Meyer and his defenders give their readers is:

Ediacaran fauna

Poof! Almost all of the the phyla appear at once, fully formed, with no transitional forms!

As I’ve said before, this doesn’t respect the science or the data.

As I’m writing this, I see that Stephen Meyer just (Finally! 4 months after I made the criticism!) put up a response on the small shellies question. And…wow, Meyer made the briefest mention of small shellies in endnote 39 of chapter 4, in an endnode on the definition of the base of the Cambrian, therefore he’s OK!

(never mind that small shellies technically predate the base of the Cambrian, so Meyer got even that part wrong)

He also confuses the question of whether the small shellies can be identified with specific groups which is debatable in many cases (but there have been several successes in doing this), with the question of whether or not they are ancestral at all. I don’t think there is anyone now who would assert they are some completely independent group. Gould half-suggested this in Wonderful Life in the tiny bit of text that he puts into the small shellies, but that was nearly 25 years ago, and the study and dating of small shellies has advanced dramatically since then. And having critters with chainmail armor just before you find fossils with full plate armor is surely not a coincidence.

Regarding dating the “Explosion”, surely it is more important to get correct the timing and sequence of events relevant to the origin of the bilaterians, than it is to quote authorities about when “the Explosion” was. At the very least, skeletons and skeletonization were evolving during the small shelly period, millions of years before the “Explosion”. How can this not be important? How could Meyer have left this out for his readers, none of whom would have checked the endnote, nor realized that a huge piece of the puzzle that was being elided there!

.

.

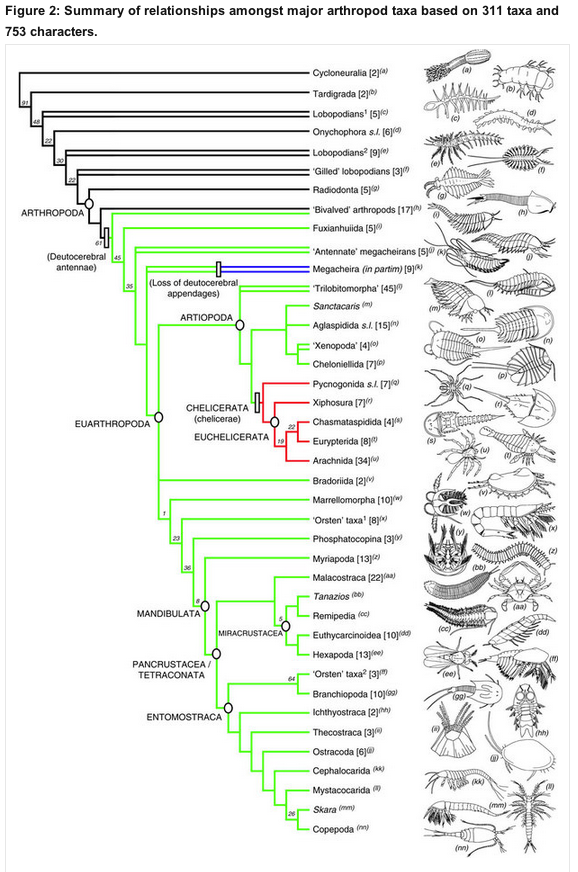

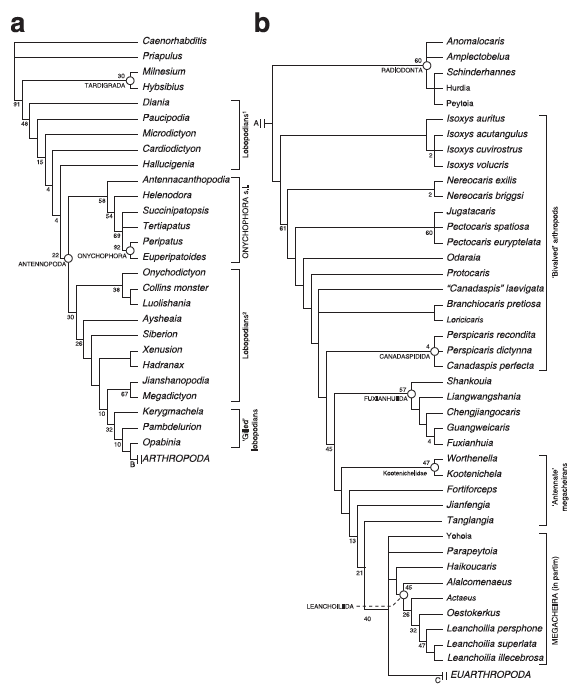

2. Meyer says that transitional fossils for the Cambrian groups don’t exist, but fossils with morphology transitional between the crown phyla do exist, oodles of them. Meyer just doesn’t have the knowledge, either of fossils or methodology, to know a transitional fossil even if it is right there in front of him. I made the basic argument previously, but it can be done even more clearly with the amazing new study by Legg et al., which coded and analyzed hundreds of characters of hundreds of Cambrian arthropods and arthropod relatives.

…and, if we zoom in on the base of the tree:

Figure 4: Phylogeny of panarthropoda (just parts a & b).

Bam!

See “EUARTHROPODA” down at the lower right? That’s the node representing the last common ancestor of all living arthropods, i.e. crown group arthropods. Bumblebees, king crabs, hummingbird moths, millipedes, shrimp, horseshoe crabs – they’re all just subgroups of that one little subgroup of these fossils. Everything branching below EUARTHROPODA on the tree lacks one of more characters that unite all living arthropods. See ONYCHOPHORA, in the middle of (a)? That’s the closest living phylum to arthropods. Between two modern crown group phyla (arthropods and onychophorans), there are dozens of species with intermediate character suites. And that’s just the species currently known to science well enough to describe and put in a character matrix. This is why I was ranting and raving about lobopods in my previous posts.

No transitional fossils? Take a hike, Stephen Meyer and David Klinghoffer!

.

.

3. Meyer claims that phylogenetic methods are worthless, but doesn’t know that phylogenetic hypotheses are statistical statements and are statistically testable through standard methods – methods which themselves are testable and well-tested. Virtually any time such methods are applied to real data, including in Cambrian divergences, there is a strong statistical tree signal, and strong congruence between different datasets, and this remains true whether or not different datasets give exactly the same phylogenetic results on any particular phylogenetic question. The most divergent results typically come from the smallest datasets – small numbers of taxa or small numbers of characters, or both (with the number of taxa being more important than the number of characters), which is exactly what any scientist would expect from any statistical inference procedure.

For actual serious information on this topic, which Meyer mentions only to then ignore, see Doug Theobald’s FAQ, particularly the section on phylogenetic tree statistics.

.

.

4. Meyer claims that the evolution of new genetic information is virtually impossible, a claim he is able to sustain mostly because he doesn’t understand the phylogenetic methods (see above) that are necessary for inferring the history of the origin of genes. Apparently he wants us scientists to think that gene sequences share similarities that fall into nice tree patterns – including, often, direct genomic remnants of duplication, transposition, and other mutational processes – just because the intelligent designer put those signals there just to make it look like evolution happened. Even some of Meyer’s colleagues at the Discovery Institute agree that Meyer is wrong here – Michael Behe and David Berlinski accept that natural evolutionary processes can produce new genes and thus new genetic information – they are apparently just too craven to admit the contradiction forthrightly.

Since Meyer’s main argument is about how intelligent design is the unique and only known cause of new information, he really is sunk even if one duplicate gene with a few mutations and little bit of new information is accepted as having occurred naturally. If it can happen one time in one species, what can happen over hundreds of millions of years across millions of species?

.

.

5. Meyer’s claim that “massive amounts” of new genetic information was required for the Cambrian Explosion is belied by the fact that gene number, and most of the key developmental patterning genes are shared broadly across the phyla, and even outside of bilaterians, rather than looking like they originated in the midst of the divergence of the phyla.**

Meyer obscures this with wild assertions about genomics and tons of “information” in the noncoding DNA. This leads us to:

6. Meyer claims that the “junk DNA” hypothesis has been refuted, and that therefore the 90+ percent of large animal genomes that doesn’t code for genes or gene regulation is actually a massive additional amount of new information, but Meyer doesn’t rebut or even acknowledge the massive, basic, evidential problems with this idea. (And, for that matter, neither does the ENCODE project or the various journalists who were snookered by this triumph of wishful thinking over hard evidnece.) The problems are:

6a. Simple calculations show that if most of the DNA in large-genomed organisms like humans was essential, given known mutation rates, we would die from fatal mutations each generation. This was Ohno’s original argument for junk DNA, and it has not been rebutted by ENCODE, the creationists, or anyone else.

6b. Genome sizes in complex animals and plants vary by orders of magnitude within many specific groups (tetrapods, onions, ferns, salamanders, arthropods, whatever), but despite this, within each group they all have about the same number of genes, and approximately the same organs and developmental complexity. The obvious and straightforward inference is that most of the DNA which is sometimes present, and sometimes absent, isn’t necessary, and probably isn’t doing much even when it is present.

6c. When you actually look at the sequences in the variable fraction of the genome, most of it looks like the product of mutational processes with no selective filtering – transposon remnants, fossil viruses, duplications and other mutational errors, etc. Furthermore, unlike genes and important regulatory regions, which are well-conserved between closely related species, the apparent junk DNA looks like it has no constraint.

Arguments 6a, 6b and 6c have not been rebutted by ENCODE, the creationists, or anyone else. They’ve hardly even been acknowledged, let alone addressed in a serious way, let alone effectively rebutted.

In the face of all of this, it staggers belief for Meyer and his defenders to think that anyone who knows the above facts will be impressed with Meyer’s book, or Klinghoffer’s ceaseless din of spin. I suspect that Klinghoffer himself sustains his energy on little more than the faith that his chosen “experts” know what they are talking about, and that they are brave rebels against the dogmatic establishment.

Earth to David: look into these topics for yourself. Pick any one of them! Read the papers, look at the raw data for yourself, and take the trouble to learn enough about the methods and data to actually do a simple analysis (a graph or phylogeny) yourself. Then start asking Meyer or other ID authorities what their explanation is, and why the evolutionary analysis is wrong. Don’t be afraid to follow the evidence where it leads – just make sure you are actually aware of the actual evidence, instead of relying on the mishmash of quote-mines and creationist misunderstandings that are tossed together in Meyer’s book.

.

.

Notes and References

* Graham Budd is the highest form of expert here, in that he a paleontologist whose speciality is specifically Cambrian organisms.

** Ditto for protein domains, etc., which are also widely distributed, and are not specific to the bilaterian phyla, so did not have to originate in the Cambrian. If a creationist/ID fan wants to talk about more remote origins, or the origin of life, that’s fine, but they should realize that by switching topics in an attempt to avoid admitting error, they have effectively admitted defeat on the original topic, which was the Cambrian Explosion.

Legg et al. (2013). “Arthropod fossil data increase congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies.” Nature Communications 4, doi:10.1038/ncomms3485