New Szostak protocell is closest approximation to origin of life and Darwinian evolution so far

by Gert Korthof

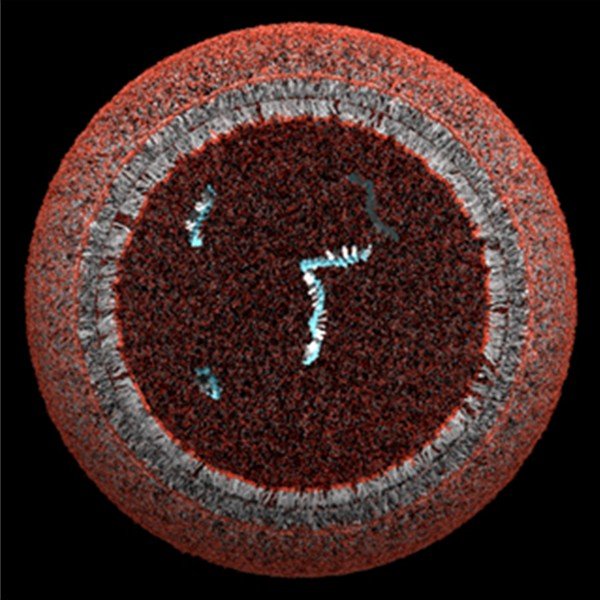

Origin of life researcher and Nobel Prize winner Jack Szostak has made an important step towards creating a prebiotically plausible protocell (prebiotic implies that it did not originate from pre-existing forms of life, but its components could have self-assembled from raw materials available under physical and chemical conditions of the early earth). The protocell is a fatty acid vesicle, which is a simpler form of a cell membrane, in which RNA replication occurs autonomously without the help of enzymes. The results have been published in Science Nov 29 2013.

This is the first time that nonenzymatic RNA copying succeeded inside a fatty acid vesicle. The big obstacle has always been that magnesium ion Mg2+ was necessary for RNA copying, but two negative side-effects of high Mg2+ levels frustrated success. Firstly, high Mg2+ levels break down the simple, fatty acid membranes that probably surrounded the first living cells. Secondly, Mg2+ catalyses degradation of single-stranded RNA. After a long trial-and-error process, Szostak et al. discovered that citrate removes these two side-effects. Citrate efficiently protects fatty acid membranes from the disruptive effects of high Mg2+ ion concentrations, while both allowing RNA copying and protecting single-stranded RNA from Mg2+-catalyzed degradation.

It would be easier to run a self-replicating RNA system (RNA replicase) in the lab without a cell membrane because the membrane is a barrier for transportation of raw materials. But the membrane is important because chemicals can be kept at high concentrations inside the cell. They are not diluted. The protocell is a unit which is spatially separated from its environment. It also is the beginning of a unit with its own internal environment. Furthermore, a unit could behave differently from other such units. For example, one unit could be more stable than another. Or it could divide more efficiently than others. So it is a good idea that the system has a primitive membrane. More advantages of a membrane will appear later.

The protocell is called a ‘protocell’ because it is very much simpler than the modern eukaryotic cell, and even simpler than a bacterium.

It would also be easier to have enzymes available, but then one would need a system that could produce enzymes, and that would require DNA and complex transcription and translation machinery. That machinery would not be available in the RNA-world. However, RNA combines the properties of an enzyme and an information carrier (ribozymes).

Why are replication and cell division important in the origin of life? The effect of RNA replication and cell division is that it produces more of the same. These processes lower the probability of accidental destruction of the whole line of protocells.

It is clear that RNA replication would benefit from the presence of a suitable membrane. But what would be the benefit for the membrane to have RNA molecules inside itself? Self-replicating RNA on its own does not make a difference for the cell. The Science publication did not mention what benefit that could be. However, in a previous publication (Szostak, 2012) Szostak suggested that “catalyzed phospholipid synthesis could confer such a selective advantage by driving protocell membrane growth through the adsorption of fatty acid molecules from surrounding vesicles.” So, if those RNA molecules were present in the protocell, we would have a system in which the components stabilize each other. The protocell would stop being an accidental, unstable combination of components. The two components would reinforce each other’s formation.

A crucial advantage of a membrane now becomes clear: the copies of RNA molecules are kept in the same compartment. After a successful cell division each daughter cell would inherit approximately the same RNA molecules and other chemicals (RNA building blocks, Mg2+, citrate, fatty acids) that contributed to the success. Therefore, the protocell would become more frequent in the population based on inherited properties. In other words: nothing less than Darwinian evolution by natural selection.

A requirement for Darwinian evolution of the protocells is that the RNA makes copying mistakes (mutations) and that these make a difference in fitness. That is certainly an easy requirement, since copying would be sloppy at first anyway. The error-prone copying would be the basis of natural selection of RNA-carrying protocells. The protocells would have the ability to improve themselves. This could be the start of life and evolution.

A working version of a complete protocell has not yet been achieved in a laboratory setting. Other problems need to be solved, such as the fact that citrate is not a plausible prebiotic component: it needs to be replaced by an alternative component. Finally, at a certain level of complexity, a third main component of the cell would be helpful: chemical energy (metabolism). Nevertheless, conceptually and practically, the Szostak protocell is the closest approximation so far to the origin of life forms which have the potential to evolve.

Sources

- Katarzyna Adamala, Jack W. Szostak (2013) ‘Nonenzymatic Template-Directed RNA Synthesis Inside Model Protocells’, Science 29 Nov 2013

- Robert F. Service (2013) ‘The Life Force’, Science News Focus 29 Nov 2013 (this is an interview with Szostak and gives useful background information)

- Researchers Find Missing Component in Effort to Create Primitive, Synthetic Cells, Science Daily 29 Nov 2013 (free access)

- Jack W Szostak (2012) The eightfold path to non-enzymatic RNA replication, Journal of Systems Chemistry 2012, 3:2 (Open Access)

- Exploring Life’s Origins (Jack W. Szostak): an educational website about the Origin of Life with animations. The illustration in this article is from work by Janet Iwasa and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.