Expanding the genetic alphabet

By Gert Korthof.

“It is a very, very hard problem. Getting all the pieces to work means re-engineering 3.5 billion years of evolution. It’s so ambitious.” These are the words of a scientist 14 years ago [1]. He was talking about the project of inventing new bases to include in DNA and let the new DNA function in a living cell. Now an important milestone has been reached towards that goal. Scientists have succeeded in adding a new base pair, d5SICS (call it X) and dNaM (call it Y), to the DNA of the bacterium E. coli and let it replicate its DNA [2]. Furthermore, the growth rate of the bacterium was not significantly slowed down, and the DNA-repair system did not remove the new bases. These results give us hope for realistic answers to the so far speculative questions as to why evolution settled on only two base pairs in DNA. Could there be superior bases and superior DNA?

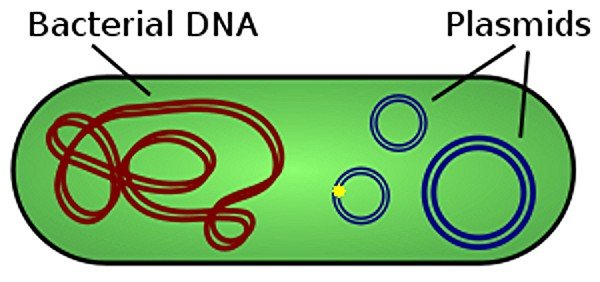

The researchers included the new base pair in a plasmid and introduced it in to the bacterium E. coli (the yellow dot in the illustration is the new base pair). The plasmid replicated including the new base pair. This is a significant result, because there are many requirements for bases in DNA in general.

For example, any base pair must enable DNA to form a regular double helix with fixed dimensions over long distances; a base must attach properly to the DNA-backbone; any base in a pair must pair exclusively to its partner and not to bases of other pairs; any base must not pair with itself; the base pairing must be strong enough to be stable, but not too strong to make the process of strand separation (required for replication) too difficult; etc.

Once new bases are developed, many new possibilities are opened. For example, consider the effect on the coding potential of the genetic code. How many new amino acids could the bacterium produce? Let’s see. We are not replacing any of the existing bases. So, the DNA of the modified bacterium has now six different bases: A,T,C,G,X,Y and three base pairs: AT, CG, XY. Any position of its DNA can be a A,T,C,G,X,Y. Three bases in a row code an amino acid. There are 20 natural amino acids. Instead of the standard 4 × 4 × 4 = 64, there are now 6 × 6 × 6 = 216 different triplets or codons. If we subtract the 3 triplets of the standard 3 stop codons - which do not code for an amino acid - we are left with 61 in the old and no less than 213 different triplets available for coding amino acids in the new bacterium.

That is, theoretically. Life on earth uses 61 triplets to code for 20 amino acids. That is a redundant coding system. On average there are about 3 codons per amino acid. Theoretically, such a coding system could code for 61 amino acids. But evolution decided otherwise. If we leave intact the redundant coding system for the standard 20 amino acids, the modified bacterium theoretically could code for 216 – 64 (including stop codons) = 152 extra amino acids. A huge gain! Proteins can be imagined with properties not possible with the standard code.

At the moment it is too early to say anything sensible about the performance of the new bases. First, the bases need to code for an amino acid, and the transcription and translation system must be working. And it would be nice to observe the new bases in the bacterial chromosomal DNA.

It would also be nice to observe the behavior of the new bases in eukaryotic chromosomes (plants and animals). Even if it turned out that the overall performance of alternative bases is inferior to the natural bases in DNA, that would be valuable information. The question whether the 4 universal bases in DNA are uniquely fit for coding the genetic information of life on earth isn’t pure speculation any more. It can now be attacked experimentally.

Science has also a short News feature about the research [4].

Notes

-

Robert F. Service (2000), Creation’s Seventh Day, Science, Volume 289, issue of 14 Jul 2000, pp. 232-235.

-

Ross Thyer, Jared Ellefson (2014), Synthetic biology: New letters for life’s alphabet, Nature, News and Views, 15 May 2014 (online 7 May 2014) (not free).

-

Denis A. Malyshev et al. (2014), A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet, Nature, 15 May 2014 (online 7 May 2014) (this is the original research article).

-

Robert F. Service (2014) Designer Microbes Expand Life’s Genetic Alphabet, Science, News & Analysis, 9 May 2014 (free).