Avida-ED Web, The Beta Release

Avida-ED is educational software that provides an accessible presentation layer on the Avida artificial life platform. The first version was released nine years ago, and today marks Prof. Rob Pennock’s release of version 3, with a formal presentation at Evolution 2016. Avida-ED is geared toward the needs of undergraduate and advanced high school curriculum use.

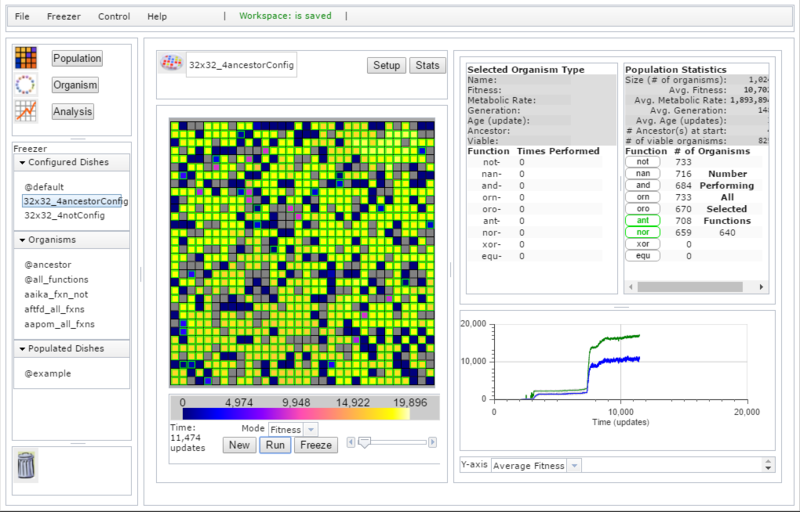

The new version, Avida-ED Web 3.0, is a web application: it runs in your browser (Firefox or Chrome currently; Safari, Internet Explorer, and Edge have some compatibility issues). To get it, visit the canonical Avida-ED site, or the mirror site. As a web application, Avida-ED Web 3.0 lowers the barriers to use, restoring the ability for those running Linux to use Avida-ED, and giving Windows users access to the latest feature set. While installation is not required, there are installers for MacOS and Windows that set up a local HTTP server and launch a local copy of Avida-ED Web in the default browser. This latter option may be useful for people who expect to be without internet access when they want to use the program. More discussion below the fold.

One of the principal conceptual advantages of Avida-ED is that it provides an instance of evolution rather than a simulation of evolution. Experiments in Avida-ED produce real data.

That said, Avida-ED presents a restricted subset of what Avida is capable of. This is by design, so as not to overwhelm its intended audience.

Avida-ED has a history as an award-winning software package and tool for teaching core scientific principles as well as evolutionary biology. The goal of ease-of-use on the front end is achieved through some pretty difficult computational challenges on the backend. Given that the PIs on the project have discussed the use of Avida-ED in various and sundry places, I thought I would delve a bit into the development issues.

The original grant for development of Avida-ED got things rolling in 2004. Let’s set the context for this. Avida is a software system written in C++, with its original version being written in 1993. Avida has had a long history of incremental development and, truth be told, feature creep. Pretty much every graduate student thesis, dissertation, and post-doc project has left its mark on the Avida codebase (including my own, which involved allowing movement of Avidians from cell to cell). It is now a large and somewhat cantankerous codebase, with some real constraints on which compilers work well to produce executable code. Having delved into that code in the past, I can tell you that there are a variety of brilliant bits of programming prowess in there, many of them due to Prof. Charles Ofria, who was one of the original authors. So by 2004, there were already eleven years of modifications to the Avida code. The Avida-ED team was looking for a way to deliver a user interface on multiple platforms, and they achieved that goal. The approach was to use Python (2.4, IIRC), PyQT 3, and PyQWT for a user interface, and communicating with Avida as a library via Boost.Python. The 2007 release of Avida-ED had separate desktop installations for Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux. There were some significant differences between the application build environments, though, and the Linux installation was cut fairly early in Avida-ED history.

In 2009, I took on doing some modifications of Avida-ED to permit building a large “dish” out of multiple configured or populated dishes. While I left later that year, this resulted in a beta release of a Mac OS X version in 2011. (There was also an update for Windows released in 2011.) By the time I came to the project in 2009, the original packages used to build Avida-ED were pretty much out of date. Getting a working build environment on the Mac took about five weeks of collaboration with the previous developer, Kaben Nanlohy. It was the single most complex software build environment I had ever encountered, and I have in my experience the build chain for the F-16 Fire Control Computer, which used a mini-computer front-end with a mainframe back-end for its edit-compile-test cycle. Simply trying to replace older tools with newer versions wasn’t feasible, given shifts in headers and APIs throughout the system. Additionally, the Boost.Python annotations to the Avida core code meant that even using a more recent version of Avida would have required a major effort to annotate the new Avida version, and was deemed out of scope.

Dr. David Bryson later took on the project to develop an Avida-ED version 2.0. This replaced the Python user interface with Objective-C, but this choice limited version 2 to the Mac OS X platform. While there was effort put into developing a version 2 code base for a Windows desktop release, that never gelled, and the Windows version remained with the earlier feature set. This ongoing mismatch in versions depending on platform was annoying to the Avida-ED team.

The Avida-ED group decided to go in a new direction: make Avida-ED a web application. The goal was to get a cross-platform code base that would obviate the need to develop for multiple different operating systems, while keeping the heavy computational requirements for evolutionary computation on the client side. The new Emscripten compiler made it possible to compile C++ code to a subset of Javascript, asm.js. Prof. Charles Ofria spent a few months working with Avida and Emscripten to determine that it was possible to convert Avida to a version that might run in a web browser. Dr. Matt Rupp of the BEACON Center was tasked with actually getting the Avida-core in shape to become a Javascript library, and create the API for communication with the user interface. In April of 2015, Dr. Diane Blackwood was brought aboard and charged with producing a new user interface for a web application version of Avida-ED, to be done in HTML5, CSS, and Javascript. I’m able to say a bit about Diane’s background and work because I happen to be her spouse and have seen the development first-hand, for those interested in full disclosure. She came to the Avida-ED project with a background in scientific research, software design and production, and high-stakes user interface research. Diane used to work for General Dynamics Fort Worth Division, where she was part of the Pilot-Vehicle Interface group. She worked on how to make critical information available and noticeable to F-16 fighter pilots, who often had other things holding their attention. In one research project there, she collaborated with researchers at the Naval Air Development Center in centrifuge studies of G-induced loss of consciousness (G-LOC), looking for the timing of onset of G-LOC in subjects following F-16 flight profiles in the centrifuge via an in-cab simulation. Diane’s master’s thesis project in biomedical engineering involved the production of a 12-channel graphical user interface implemented in an MS-DOS application, allowing data visualization of electromyographic and movement data in jaw fracture patients in two treatment classes. Other projects Diane has worked on prior to coming to Michigan State University included accurate acoustic recognition of marine mammal whistles in two species during hearing tests, training and testing spiders in visual acuity tests, and assessing effects of oil and gas development noise on lekking sage grouse. Diane’s interdisciplinary background and user interface expertise helped ground the work on the new Avida-ED Web user interface.

The feature set of the Avida 2.0 Mac version was used as the baseline for the new Avida-ED version. But because there was no code overlap in the user interface between the new version and previous versions, pretty much every aspect of the user interface came in for scrutiny on usability. Color maps were generated and run through simulations of various forms of color-blindness and examined for perceptual uniformity. Discrete colors for ancestors were chosen to maximize distinctness in the most-often used numbers of ancestor Avidians. Cues for the alignment of statistics labels and numbers were added. The flexibility and variation in expected browser screen sizes meant that the former fixed application size was no longer an option, so setting up an interface that added the ability to resize page elements was critical. A new feature made possible by Matt Rupp’s Avida-side work was the identification of non-viable organisms in the grid, which are now displayed in gray.

This isn’t to say that the new version fixes everything or is free of bugs. (This is a beta release, remember. Please do send bug reports from the “Help” menu, which will be added to the Github repository for the project.) But it has accomplished the goal of getting a new cross-platform code base that is ready for the future. Avida-ED version 3.0 is expected to carry the project for a couple of years until Prof. Ofria’s Empirical project is ready for use as the basis of both Avida and Avida-ED. In the meantime, a side-effect of having the web application is the possibility of leveraging it for connection to and display of data in Avida processes running in the High Performance Computing Center at MSU (see this issue for Avida). A substantial difference in operation concerns Avida-ED workspaces and filesystems. As a web application, Avida-ED Web has no automatic access to the local filesystem. Avida-ED 2.0 could store and update workspace components automatically, but saving one’s work in the form of workspaces requires manual intervention in Avida-ED Web. (The workspace from Avida-ED Web is backwards-compatible with Avida-ED 2.0 on the Mac.)

The Avida-ED Web version 3 software got its alpha test at the start of the month, as it was used by the participants in the second annual Active LENS workshop. At the wrap-up, each team made a presentation on how they would incorporate Avida-ED into their curricula. There were lots of ideas on leveraging the platform to communicate basic scientific concepts as well as concepts specific to evolutionary biology. One of the teams proposed a set of brackets for student-submitted evolved Avidians, where the Avidians would compete head-to-head in runs, the whole thing to sync up in time with the NCAA basketball playoffs. The past and present workshop participants are set up to use the collaborative QUBESHub quantitative biology community platform for post-workshop interaction. The Avida-ED Curriculum Group, with principal investigators Profs. Rob Pennock and Jim Smith, and members Dr. Loiuse Meade, Dr. Mike Wiser, and Wendy Johnson, are re-working past materials for previous Avida-ED versions to bring them up to date with the new Avida-ED Web, and are collating and developing new curriculum content.

It is planned that work will go into a version that can run nicely on iPad and Android tablets. Expanding known compatibility to ChromeBook devices is another item on the “to-do” list.

Give Avida-ED Web 3.0 a try. It ‘s a click away…