Left and right shake hands

Heritability refers to the variation in a trait that is due to the genetic variation among the individuals in a given population. It is not the same as inherited or inheritable: having five fingers is inherited, but not heritable, since there is essentially no variation and virtually everyone has five fingers. On the other hand, having long, skinny fingers or short stubby fingers is (I presume) heritable, since there is considerable variation among the population. In the same way, having a brain (so to speak) is inherited, but everyone has a brain, and there is no variation. General intelligence, on the other hand, varies among the population and may well be heritable or partly heritable. Robert Plomin of King’s College London estimates that what he calls the “genetic influence on measured intelligence” is perhaps 40-60 % in adults.

The purpose of this article is not to discuss whether intelligence is heritable, but rather what certain of my fellow leftists think about it. I raise the issue because of a recent – and courageous – article by Luana Maroja, a professor of biology at Williams College, in The Atlantic magazine. Professor Maroja estimates that the heritability of intelligence among humans is perhaps 50 %. She bemoans (and that is perhaps not too strong a word) that

some students argued instead that it is impossible to measure IQ in the first place, that IQ tests were invented to ostracize minority groups, or that IQ is not heritable at all. None of these arguments is true. In fact, IQ can certainly be measured, and it has some predictive value. While the score may not reflect satisfaction in life, it does correlate with academic success. And while IQ is very highly influenced by environmental differences, it also has a substantial heritable component; about 50 percent of the variation in measured intelligence among individuals in a population is based on variation in their genes [here she cites Professor Plomin, above]. Even so, some students, without any evidence, started to deny the existence of heritability as a biological phenomenon[,]

in part because of their “a priori moral commitment to equality, anti-racism, and anti-sexism.”

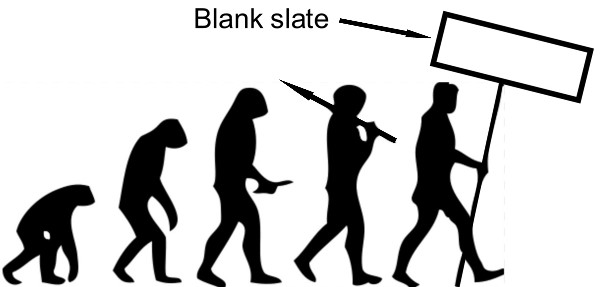

Professor Maroja goes on to observe that some of her students see “only what they want to see and [deny] real-world phenomena that conflict with their ideology.” She particularly notes that people “expect an equal sex ratio across academic professions and sometimes ascribe the lack of such equality to bias” but argues instead that male and female students may have different preferences, and women left to their own devices gravitate toward the humanities. Surprisingly, she points out that there are relatively more women in Stem fields in Algeria than in Norway; the explanation is left as an exercise for the reader, though you can, of course, read the article. Nevertheless, she argues that, if you assume “that everyone is a blank slate, differences between what males and females do can be explained only by bias and harassment,” which is “what happens when ideology replaces biology.”

I do not like to quote someone so extensively, but Professor Maroja’s final paragraph is so well argued that I want to present it in its entirety:

When students at Williams or anywhere else try to protect their worldview by denying scientific evidence, it is bound to affect what professors teach and how they teach it. Campus norms proscribe any discourse that might offend women, minorities, or anyone perceived as a victim of patriarchal white societies. However, this rule, no matter how well intentioned, is harming the very people it aims to protect. The argument favoring a certain amount of self-censorship is that it is necessary to protect minority students from feeling unsafe when they hear what they see as "hate speech." However, by not talking about science that some find unsettling, we deny students opportunities for learning and for intellectual empowerment. How well can they argue their positions effectively unless they are seeing the world as it really is?

I do not know nor for the purpose of this article do I care whether intelligence is heritable. The bottom line is this: The creationist right denies evolution for what are explicitly religious reasons, though some pretend otherwise. Much of the academic left denies evolution because of certain strongly held a priori beliefs that they hold with an almost religious devotion.

Acknowledgments. I first ran across Professor Maroja’s article in a blog post by Jerry Coyne. Emily Willoughby of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities graciously read the manuscript and offered a couple of pointers.

Appendix 1. Despite being perhaps overly coy above, I rather suspect that intelligence is heritable. Robert Plomin of King’s College London explains in his Scientific American article that genes are thought to account for 40-60 % of the difference of intelligence among different people. In an earlier article, Professor Plomin averred that the relevant genes had not (yet) been discovered; he was quoted out of context in The Guardian in an effort to claim that, because we have not found the genes, they must not exist. Marcus Munafò of the University of Bristol later refuted that article in a follow-up article that described how we know that intelligence is partly inherited. More recently, Professor Plomin and Sophie von Stumm state in a review paper that researchers have discovered genetic variances that account for approximately one-fifth of the total heritability of intelligence. An editorial in Nature noted that the heritability of intelligence is completely uncontroversial among geneticists and stated three reasons why it is controversial among the public: fear of determinism, fear of eugenics, and fear of racism. Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate employs similar arguments. Finally, Jonathan Kane and Emily Willoughby posted a review General intelligence: What we know and how we know it here on PT.