Cranky Uncle vs. Climate Change: book review

Several years ago, I sent a copy of Jeffrey Bennett’s book, A Global Warming Primer: Answering Your Questions about the Science, the Consequences, and the Solutions, to the EPA administrator, Scott Pruitt. The current EPA administrator, Andrew Wheeler, is not as obvious a climate denialist as Mr. Pruitt, but at best he downplays the IPCC report and the importance of global warming, and I think he would probably profit from a close reading of the new book Cranky Uncle vs. Climate Change, by John Cook. Dr. Cook is the founder of the influential website SkepticalScience.

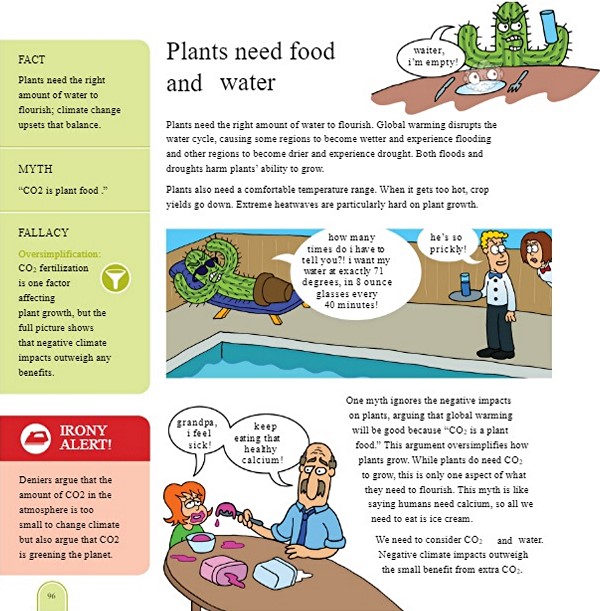

Dr. Cook, a psychologist, focuses on countering misinformation (or, as I would insist, disinformation) about climate change, according to his Amazon biography. He is a research assistant professor at George Mason University and also an excellent artist. To give a feel for the book, I will reproduce one page:

Many, perhaps a plurality of the pages are arranged approximately like this one: some text, amusing drawings including often conscionable puns, a sidebar that generally goes Fact – Myth – Fallacy. Early in the book the author lists a few fallacies and lets others leak out as needed; he supplies a sort of genealogy at the end of the book. He also summarizes in tabular form all the Fact – Myth – Fallacy arguments he covers in the book. In this case the fallacy is oversimplification.

The book is only about 160 pages long, depending what you count, and (like Bennett’s book) it is remarkably encyclopedic. It is divided into six parts: How did climate change get so controversial, denying reality, denying responsibility, denying consequences, denying science, and responding to science denial. That is a lot of denying, but then there is a lot to go around. In case you wondered about the title, the denialist is the cranky uncle you see on the cover.

The section on how climate change got so controversial includes, among other things, a comparison with Big Tobacco and a page on what the fossil fuel industry knew, as opposed to what it did. The author warns us to look out for fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations, cherry picking, and conspiracy theories. The logical fallacies are not those you will find in a philosophy textbook, but include ad hominem arguments, oversimplification, misrepresentation, red herring, and more. I did not count, but I thought that the most common fallacy was cherry picking.

The next section deals with, for example, denialist claims that glaciers are not melting and notes that the majority of glaciers are indeed melting, while denialists cherry-pick a few that are growing. The idea that Greenland was called Greenland because of a bait-and-switch by Erik the Red and not because it was particularly warm was amusing.

Denying Responsibility explains clearly how we know that anthropogenic carbon dioxide is warming the planet. In one droll cartoon that mocks those who point to the relative scarcity of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, Dr. Cook shows Cranky Uncle pointing to a glass of water that has only a minimal amount of arsenic in it and in another frame explaining to a policeman that he has only 0.08% blood alcohol. Denying Consequences shows that heat waves are getting more frequent and hurricanes more intense. Instead of concentrating on polar bears, however, I thought he could have spent a couple of pages discussing coastal flooding, which is apt to cause tens if not hundreds of millions of refugees in countries like Bangladesh.

I could have lived without the conspiracy theorists, looking a little bit like medieval monks in their black hoods. And I thought that the references to Donald Trump were possibly misplaced and may make the book look dated very quickly: I have high hopes that this book will outlast the Donald Trump presidency.

I bought the Kindle edition of the book and read perhaps half of it on a Chromebook while baking bread. The text was simply too small, so I read the rest on a computer monitor that is about 20 cm high. Reading was completely hopeless on my admittedly very old Kindle Paperwhite. According to Amazon, the paperback is 8 in, or 20 cm, square, so approximately the same size as the display on my computer monitor. I think I would find the text a little small.

The Kindle version has no index; presumably the print version also lacks an index. That is not so bad in an electronic book, except that the search feature is “not yet enabled” [my emphasis]. It would have been helpful if the Fact – Myth – Fallacy table at the end of the book had included page numbers. The typography is sometimes poor, with a few lines of type overlapping other lines and with occasional words looking like thi s. I also found it difficult to read the green type on a green background, as in the sidebar in the preceding figure. It seems to me that an upgrade is in order.

But much of that is carping, which is, of course, what critics are paid to do. On the whole, I thought it was a splendid book, and I am tempted to send a copy to Andrew Wheeler at the EPA.