Canceling Huxley; is Darwin next?

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones.

—Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

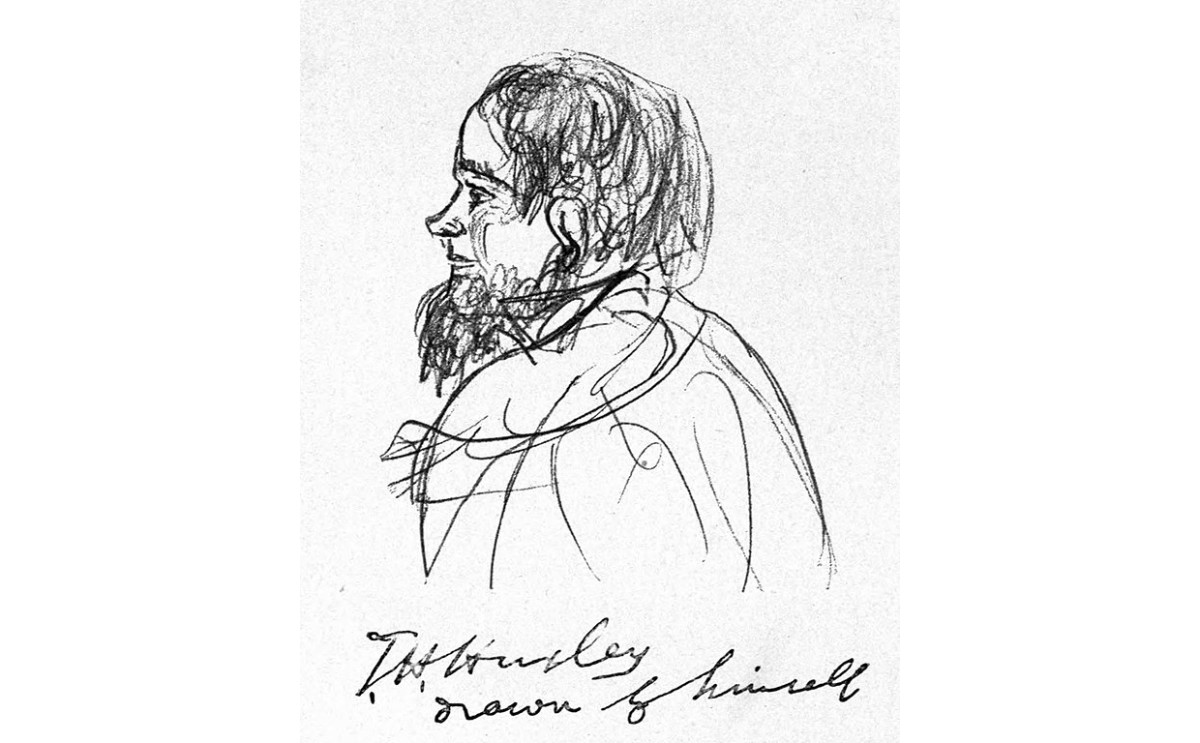

Ask Thomas Henry Huxley if you do not believe Marc Antony. According to an article in AS Review, Thomas Huxley: Once Respected, Now Rejected, a big brouhaha has erupted over the name of the Huxley College of the Environment at Western Washington University. The issue is important, because if people succeed in “canceling” Huxley, possibly Darwin will be next.

Huxley’s “sin” is to have held many of the same views regarding race as most of his contemporaries. More specifically, according to the historian Nicolaas Rupke, Huxley

formulated what became known as ‘Huxley’s Law’ or ‘Huxley’s Rule,’ which stated that the distance in biological, evolutionary development between the highest and lowest humans is greater than the distance between the lowest humans and the highest apes (chimpanzee, gorilla), thus degrading native peoples across the British Empire.

True, as nearly as I can determine, but the term Huxley’s Law is not in common use and appears to have been coined by Prof. Rupke himself, here. Indeed, the distinguished philosopher of biology, David Hull, has noted in a book review that “nothing today goes by the name of Huxley’s Law.”

The president’s office at Western Washington University has appointed a task force and solicited comments regarding renaming the College. They asked three questions:

What role did Huxley’s beliefs on race occupy in his intellectual works, his public statements, and his life as a whole? Were they remarkable in the context of the time and place in which he lived?

Did Huxley’s scientific work contribute, either in support or opposition, to the development of scientific racism and Social Darwinism, both during his lifetime and after? What portion of his total work did these contributions occupy, and how significant are those contributions in supporting or refuting the ideology of scientific racism?

What harmful institutional practices, policies, or general practical consequences, if any, can be specifically traced to Huxley’s views?

Consistently with the quotation from Shakespeare, above, they did not ask a single question about Huxley’s many accomplishments, which, I take it, are to be interred with his bones.

I read the submissions by Prof. Rupke, who is a professor of history at Washington and Lee University; Paul White of the Darwin Correspondence Project of the University of Cambridge; Sherrie Lyons of Empire State College; Michael Reidy, Professor of History, Montana State University; and an article in the Seattle Times, Reconsider cancel-culture target at WWU, by Steve Hollenhorst and Wayne Landis, both professors and administrators at Huxley.

The submissions that I read, save that of Prof. Rupke and the AS Review article, seem to me to be generally favorable toward Huxley. If you want to read one piece, read the article by Hollenhorst and Landis. I think they get it about right: Huxley’s main crime was living in the 1800’s and sharing many of the attitudes of his contemporaries. But in fact he was well ahead of his contemporaries in being an abolitionist in a country that largely supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Sure, he thought that the British aristocracy was in some way superior to the “primitive” peoples in Africa or Australia; who in 1880 did not? Let us be careful to avoid the fallacy of presentism. Despite his bias, Huxley opposed slavery and fought against social Darwinism on moral grounds. Even Lincoln, I should add parenthetically, wrote in the New York Times, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it….”

It might have been catty of them, but Profs. Hollenhorst and Landis opened their article with the observation that their university, Western Washington University, is named indirectly after a slave owner: George Washington. If I wanted to be catty myself, I would add that Prof. Rupke’s university, Washington and Lee University, is named after both Washington and the famous defender of slavery, Robert E. Lee.

Cattiness aside, I would like to let Profs. Hollenhorst and Landis get the last word:

The distinguished historians WWU asked to look at the issue overwhelmingly concluded the claims just don’t hold up. Huxley’s early writings did reflect the prevailing bigotry and prejudice of Victorian society, although even then to a lesser degree than his scientific peers. By the 1860s, he became a vocal abolitionist and by the end of his life called for universal equal rights regardless of race or gender. The beautiful irony of his scientific work on human diversity is [that] it ultimately leads him to see the oneness, and equality, of all humanity.

And, further,

Huxley later expanded these ideas in his great battles against social Darwinism and religion, which he saw as grounded in the dark forces of authority, bigotry and superstition. He feared they led to social order based on competition, subjugation and inequality. In this he was prescient, for indeed both have been used to justify not only laissez-faire capitalism and political conservatism, but also colonialism, eugenics, racism and eventually fascism.

Also,

It’s telling he didn’t teach at Cambridge or Oxford, but rather working-class institutions, the Royal School of Mines and later Imperial College, where he brought science and industry together to solve societal problems. He gave hundreds of free public lectures to common folk. As an early advocate for public education, he was elected to the London School Board, where he worked to bring a decent education to ordinary people and implemented the first training for science teachers. In other words, he’d make an exemplary WWU faculty member today.

What would Huxley say about his legacy? First, he’d commend us for interrogating it, especially the brave students, who without power and risking reproach, stood up to raise the issue. But he’d then remind them that “it is not what we believe, but why we believe it. Moral responsibility lies in diligently weighing the evidence.” And to all of us he’d likely say, “learn what is true in order to do what is right.” Now that the question is before us, address it with honesty and integrity.

And, finally,

Don’t be fooled. Huxley’s message isn’t privileged. It isn’t elitist. It isn’t racist. It’s timeless. The values he fought for are at the core of public higher education to this day. Far from causing harm, we are in a better place because of Thomas H. Huxley.

I shall add, finally, and not entirely parenthetically, that Profs. Hollenhorst and Landis trace the association between Huxley and social Darwinism to a notorious fabricator, Henry Morris, the founder of “scientific” creationism and himself something of a racist. It is partly because of this background that I fear that if Huxley is “cancelled,” then Darwin is next.