All theories in science involving randomness are invalid

Contemporary theories of evolution involve mutation as the ultimate source of variability, and model it as having a distribution of directions which is independent of the needs of the organism. It is natural selection that provides the directionality of evolutionary change. There can hardly be any assertion in the theory that is more disliked by creationists and ID advocates. Now they have found a way to oppose this view: argue that randomness cannot be part of the explanation of any phenomenon that we claim to have explained scientifically.

Alas, there is an unfortunate side effect of this position: many scientific theories have to be tossed out if we accept it. Let me explain …

The general principle was stated by Eric Holloway, in a post “Randomness is not a Scientific Explanation” on the Discovery Institute’s site “Mind Matters” on 9 August 2021. Mind Matters, a blog of the DI’s Walter Bradley Center for Natural and Artificial Intelligence, is devoted to making profound arguments as to why artificial intelligence will forever remain unintelligent, because only supernatural forces can create an intelligent system. The article was of course immediately greeted with enthusiasm at Uncommon Descent.

Here is Holloway’s argument:

It is common in the sciences to claim aspects of our universe are random:

- In evolution, mutations are random.

- In quantum physics, the wave collapse is random.

- In biology, much of the genome is random.

- In business theory, organizational ecologists state new ideas are random.

There is a general idea that everything new has its origins in randomness. This is because within our current philosophy of science, the two fundamental causes in our universe boil down to randomness and necessity. Since necessity never creates anything new, then by process of elimination the source of newness must be randomness. Similar to how the ancient Greeks believed the universe originated from chaos.

Here’s the irony of the view that whatever is unique in our universe is random: We can never know if anything is truly random. This is because randomness is unprovable, which was proven by three different computer scientists: Ray Solomonoff, Andrey Kolmogorov, and Gregory Chaitin. The only thing we can know is that something is not random. Hence, we can never know that something originated from randomness.

What does this result mean for science? It means that randomness can never be a scientific explanation, since we can never know that something is random. At best, saying something is random is shorthand for “we don’t know”. So, when scientists state the origin of something in our universe is random, they do not know the origin.

Well, that takes care of it, doesn’t it? Instead of modeling the mutational process as random, in order to be part of a scientific theory, we must describe the actual causes of mutation so as to be able to predict individual mutations. Right?

Well, not so fast. Are there other models used in science that involve random events? Yes, definitely. Here are a few I can think of:

- Random times of decay of radioactive atoms.

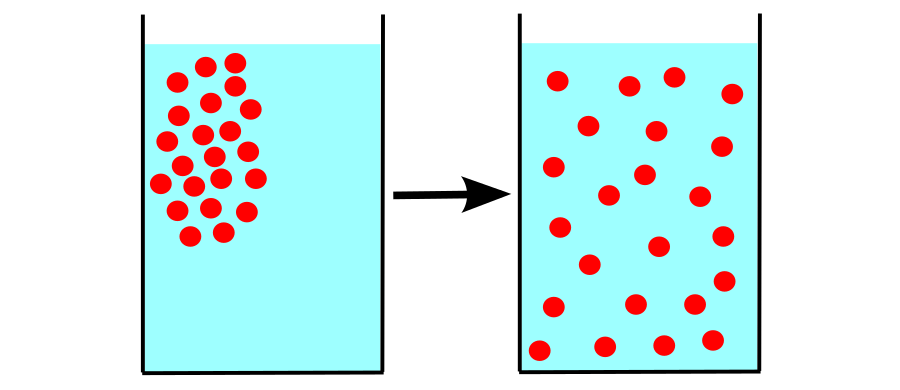

- Random movements of molecules when they diffuse in solutions.

- Brownian motion of particles in gases or liquids.

- The movement of molecules in a gas, and the distribution of velocities that results.

- Random segregation of chromosomes in meiosis.

- Random changes of gene frequency in a population (random genetic drift).

- Rolls of dice, spins of roulette wheels, or fall of cards in gambling.

Those are just the ones I can think of, I’m sure there are many more. If Holloway’s argument is accepted, all of these successful scientific theories will need to be discarded Maybe even probability theory. The Discovery Institute has just carried out the greatest revolution in scientific explanation ever. Or tried to, anyway.

Note that none of these theories actually asserts that the universe is fundamentally stochastic, or fundamentally deterministic. It just has phenomena in it that are well-modeled by models involving randomness, which is a much more limited assertion.

If someone wants to argue that the argument applies to its original intended target but not to any of the phenomena on the above list, I would be interested to hear that. Though I may be profoundly skeptical of that.

So, does Holloway’s argument work? Has science been revolutionized? Any discussion?

I wish to thank the Discovery Institute for making a science blogger’s life easy.