Devolution of language? Or of thought?

A correspondent the other day sent us a link to an article with this intriguing title, ‘We conclude’ or ‘I believe?’ Study finds rationality declined decades ago. The study, out of Wageningen and Indiana Universities, suggests that since 1980 public interest has shifted from rationality toward emotion. Those who think we are in a “post-truth” era will not be surprised. It seems to me that this trend, if substantiated, shows that we may be veering away from scientific thinking and evidence to unfounded opinions and unsubstantiated claims.

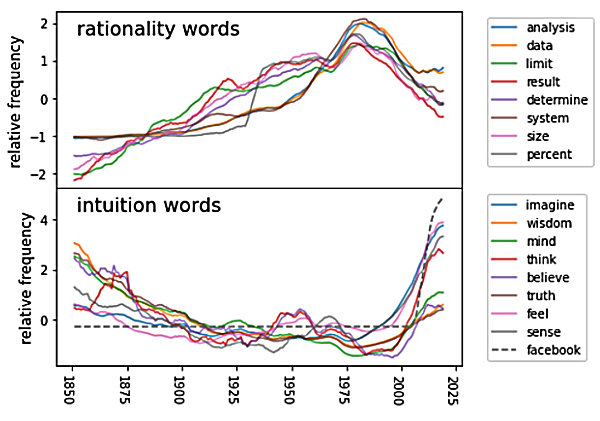

The figure above, which does not appear in the paper, leaves something to be desired: We are not told the units of the vertical axes. I am going to guess that they are standard deviations of something. No matter, we can get the drift; from 1850 to 1980, rationality words increased steadily in frequency, whereas intuition words decreased. From 1980 to now, by contrast, rationality words have decreased sharply while intuition words have increased sharply. The figure gives a handful of each type of word (note that “think” and “truth” are counted as intuition words). The dashed line represents the frequency with which the word “facebook” appears; I do not know why it is not quite 0 for the first 150 years of its nonexistence.

Using Google nGram data, the researchers analyzed the language in millions of books and, in the words of the Phys.org article,

found that words associated with reasoning, such as "determine" and "conclusion," rose systematically beginning in 1850, while words related to human experience such as "feel" and "believe" declined. This pattern has reversed over the past 40 years, paralleled by a shift from a collectivistic to an individualistic focus as reflected by the ratio of singular to plural pronouns such as "I"/"we."

I had a look at the original article, The rise and fall of rationality in language, by Marten Scheffer, Ingrid van de Leemput, Els Weinans, and Johan Bollen. Unfortunately, the article was not written in English, but in a closely related language called Statistics. I know a few words of Statistics, so I managed to decipher the article and get the gist of it.

The authors studied the language in millions of books published between 1850 and 2019, using Google nGram data. As the first link above notes, they found first an increase then a decrease in rationality words such as determine and conclusion. They found this pattern in both fiction and nonfiction. As a control, they analyzed words in the New York Times and found similar trends. They also performed similar analyses in Spanish to ensure that the findings were not an artifact of English.

The authors also identified two opposite “poles”: the personal and the societal. The personal pole prefers words that they classify as related to belief or intuition, the body, or various activities. The societal poll prefers words related to science and technology. The authors tentatively relate the personal pole to what they call intuitive thinking, and the societal poll to rational thinking.

Importantly, this fall of rationality is not just the result of scientists’ taking my advice and writing in the first person singular when appropriate; it seems to be happening throughout books and periodicals. As the authors note in their abstract,

… this reversal occurs in fiction as well as nonfiction. Moreover, the pattern of change in the ratio between sentiment and rationality flag words since 1850 also occurs in New York Times articles, suggesting that it is not an artifact of the book corpora we analyzed. Finally, we show that word trends in books parallel trends in corresponding Google search terms, supporting the idea that changes in book language do in part reflect changes in interest. All in all, our results suggest that over the past decades, there has been a marked shift in public interest from the collective to the individual, and from rationality toward emotion.

I contacted several people, and one of those contacted yet another. One of my correspondents was skeptical of doing a principal components analysis on z-scores; that is Greek – I mean Statistics to me. He suggests also that electronic publishing has enabled many, many books that (shall we say) would not have made it as far as an acquisitions editor; he suggests looking at library classification codes, which he thinks are

obviously a much more reliable indicator of semantic content than are the frequencies of certain words designated as semantic markers of “individuality,” “rationality,” etc.

As for the Times, I agree that it has largely pivoted toward feature articles, and doing so may have simplified its terminology.

The person who was contacted by my correspondent pointed to

[l]ess passive construction, more agency in the nouns—both of which tend to shorten the length of sentences, making them easier for readers to read, but also taking up less paper for folks who print these papers.

Additionally, some time after 1980, certainly by 2000, self-published books and self-help books may have altered or distorted the vocabulary. Indeed, as one of my correspondents has noted, in 1850,

"educated" people learned Latin and Greek, and a lot of their writing reflected the grammatical and syntactical influences of those languages (Latin more than Greek). … As we dropped the pretense, scientific communication became more crisp and colloquial.

The other issue was that these highly "educated" individuals were almost all of social classes that did not "work" for their money. This was a group of privileged individuals, and one way of marking that privilege was with language: … the writing resembles English, but it has a frame of reference that is all its own, and those standing outside the frame often cannot penetrate it.

[Thus,] there is a trend to break down the rhetorical structures that exclude broad swaths of people who might make up a more diverse audience (and market). There certainly is a profit motive, but there is also (potentially) a communitarian motive: people do better if they have easier access to accurate information, so changes in rhetorical structure might be a way to accomplish this [that is, easier access to information] (albeit with downsides as the current COVID outbreak shows us).

I do not know whether this last analysis explains why the turning point is around 1980, but I will let it be the last word.