The Evolution of T-URF13: Does Irreducible Complexity Count or Not?

A response to the evangelical Discovery Institute (and others)

The Discovery Institute, principal advocate of the Intelligent Design (ID) movement in the US, attempts to invalidate scientific results demonstrating that so-called irreducibly complex (IC) biological traits can evolve naturally. According to the ID protagonist Michael Behe (1996), a system is by definition irreducibly complex if it consists of several specifically interacting components which together produce a function such that the removal of any single component leads to the failure of this function. Most biochemical systems are irreducibly complex in that sense. Since they cannot be less complex without losing their function, unguided natural processes based on random mutations and selection cannot build them up gradually, according to Behe. Instead, multiple coordinated mutations would be required simultaneously.

Behe postulates that a stepwise evolution of such systems is too improbable to have happened if more than two coordinated mutations, two specific binding sites among proteins, or two specific interdependencies between the parts of a system were established in one fell swoop. Such systems are beyond the “edge of evolution,” Behe says, and need an intelligent creator. This is the so-called argument from irreducible complexity (IC argument).

However, within the last 25 years, ID advocates were faced with more and more logical arguments and empirical data which made apparent that their perception of how evolution works is untenable. One intriguing example is the evolution of a mitochondrial gene in the corn plant Zea mays named T-URF13 which encodes a ligand-gated pore forming receptor protein called URF13 protein (Hunt 2007).

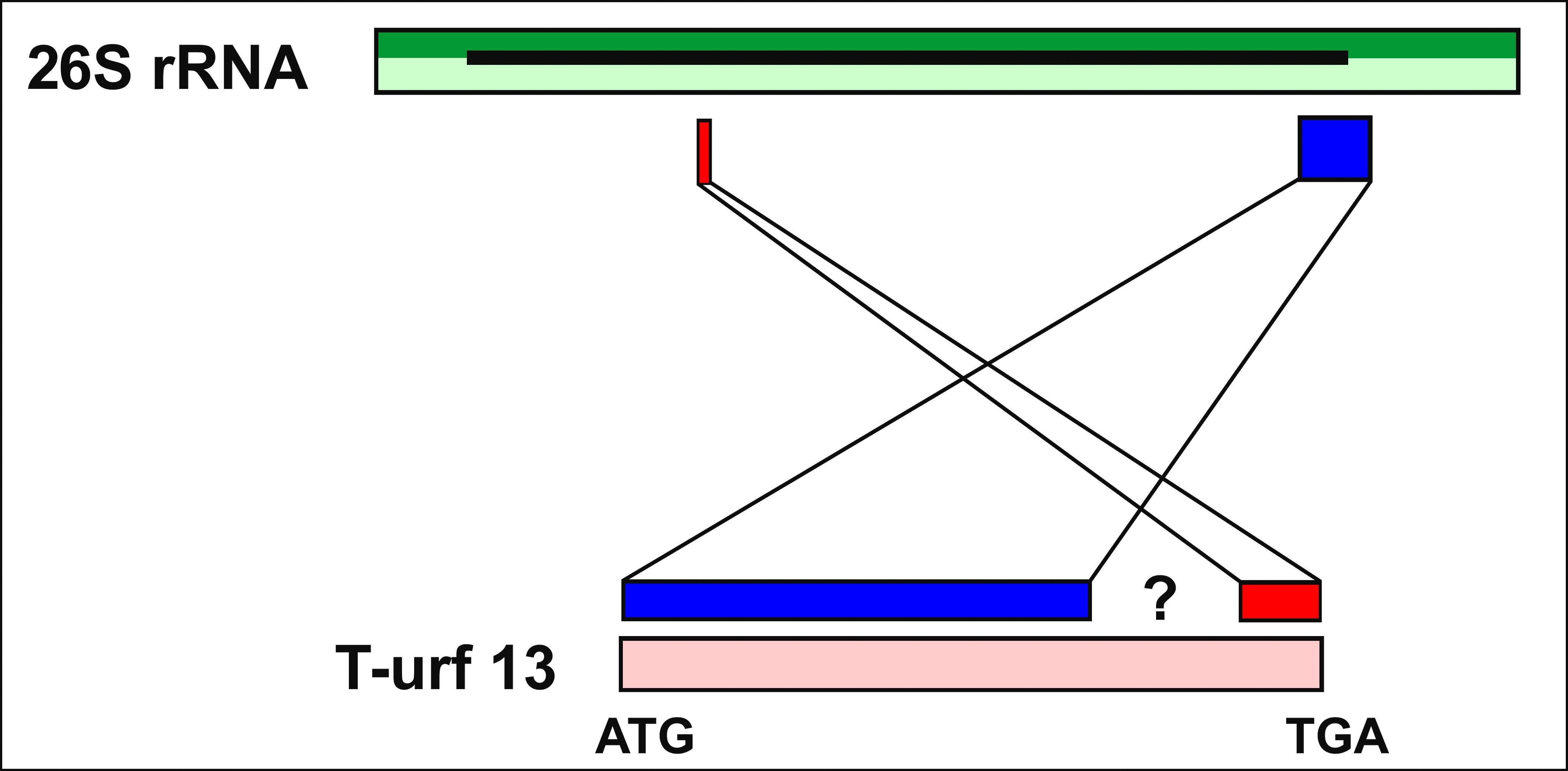

This membrane protein evolved in cultivars bred for male sterility called Texas cytoplasmatic male-sterile maize (cms-T maize). Data show that T-URF13 has arisen by rearrangements involving recombination events from two different fragments of the mitochondrial gene coding for 26S rRNA (see Fig. 2–4). The latter is a special type of non-coding but functional RNA molecule, which is a pivotal component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. In short, male sterility in the cms-T cytotype is linked to the chimeric mitochondrial gene T-URF13 (Bosacchi et al. 2015).

Remarkably, the URF13 protein comprises various distinct, specifically interacting elements that are functionally independent of each other. But all of them are needed to accomplish its specific function:

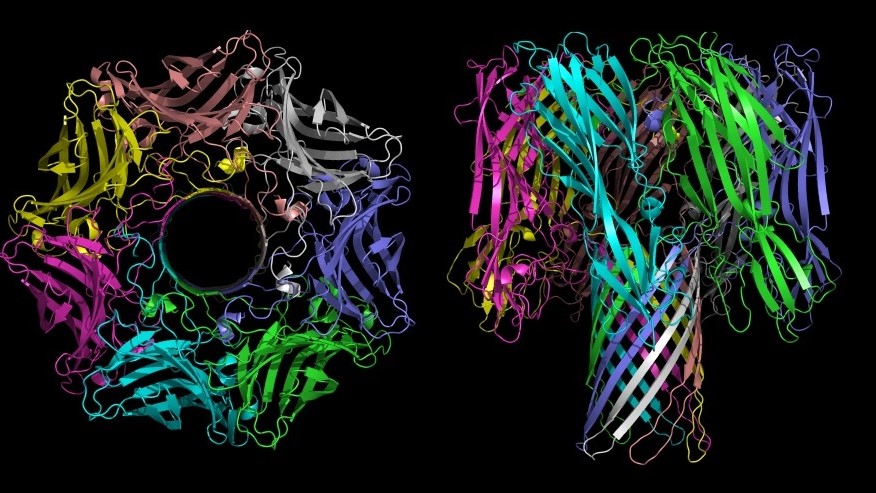

- The URF13 molecules have specific contact regions organizing themselves to a multimeric protein complex in the membrane (Fig. 1).

- The complex forms an ion channel switching between two defined conformational shapes which open and close the ion channel. This trait requires additional specific complex boundary conditions.

- The protein complex comprises a specific binding site for certain signaling molecules that open or close the channel.

URF13 thus displays all fundamental properties of gated ion channels, which, interacting with other transport proteins, control the uptake or excretion of substances into or out of cells. It was found that the sensitivity of cms-T maize for the toxin of the fungus Bipolaris maydis is also linked to this property: The toxin binds to URF13 protein and opens the ion channel, resulting in a massive loss of vital ions such as Ca2+ and NAD+ (Braun et al. 1989). There is some evidence that an analogous mechanism is responsible for the male sterility (Levings 1990, p. 947). URF13 protein specifically reduces mitochondrial activity in the tapetum cells of the anthers. The resulting lack of energy leads to the degeneration of the tapetum cells. This suggests that a signaling molecule inside the tapetum cells also binds to URF13 protein and opens the ion channel, leading to the loss of energy carriers.

What is the pivotal point? Notably, according to Behe, those specifically interacting parts and their coordinated binding sites constitute an irreducibly complex system. Intriguingly, the URF13 protein is equivalent, regarding its complexity and functional role, to another irreducibly complex three-component system discussed by Behe (1996, pp.108–110); see Hunt (2007). But whereas Behe asserts that billions of years would not suffice to get such systems naturally, URF13 evolved within a ridiculously short period of less than a hundred years, barely a blink in evolution.

Accordingly, Lents (2019) criticized Michael Behe’s new book Darwin Devolves and advocated T-URF13 as a result of “random tinkering.” The natural evolution of such a system from functionally unrelated genes which do not even encode proteins (and never did so in their history) indeed disproves Behe’s IC argument.

The response of the evangelical Discovery Institute

McLatchie (2019) tries to invalidate the T-URF13 protein as an example for the evolvability of irreducibly complex systems. He summarizes his refutation in four points (given below in different order):

- It is exceedingly unlikely that T-URF13 arose de novo by unguided mutations. This, in itself, is a prima facie reason to consider alternative explanations.

- The T-URF13 evolutionary claim is a “just-so story,” and no demonstration is offered of “textbook” evolutionary mechanisms accounting for its origins.

- T-URF13 turns out to be a deleterious feature, rather than one that is beneficial to the organism. Therefore, the case is possibly consistent with Behe’s thesis in Darwin Devolves.

- URF13 is a mitochondrial protein regulated by a nuclear gene, suggesting a scheme where T-URF13 did not arise from scratch, but arose instead from a “devolutionary” process which broke the regulatory mechanism of some normally useful protein.

The flawed probability argument

The main objection against an “unguided” evolutionary origin of T-URF13 refers to the well-known probability argument. The premise is as follows: Neither the phylogenetic timeline nor the limited number of individuals involved seems sufficient (in such a case) for the emergence of an irreducibly complex system, since it allegedly requires synchronized, complex mutational events consisting of several independent steps. Yet such evolutionary processes obviously did happen!

As we will see, all data support the finding that the irreducibly complex URF13 protein emerged within a few decades from sequences lacking any genuine protein-coding capability. That supports the thesis that gene sequences which accomplish irreducibly complex functions are not as improbable as Behe supposes. The immunization tactic of the Discovery Institute, once again, aims at disputing the evidence, which refutes their premise, by referencing to just the same, obviously flawed, probability argument!

Such a combination of events in, to borrow Hunt’s words, ‘one fell swoop’ does indeed seem highly improbable to occur by chance. This is especially the case given that it is estimated that only 1040 organisms have lived in the entire history of life on Earth … That is too few by a factor of 1020 for T-URF13 to evolve de novo. And, of course, if we consider the numbers of eukaryotes, or individuals of maize, the number of trials available to generate a complex feature like T-URF13 is drastically reduced by many orders of magnitude. In fact, surely such a strong improbability should prima facie cause us to consider alternative explanations to the one offered by Hunt, namely, that the T-URF13 ion-gated channel arose by chance ‘in one fell swoop.’ [McLatchie (2019)]

This is a circular argument that can be used to reject all conceivable evidence for the origin of irreducibly complex systems a priori! It is therefore clear that the probabilistic calculations are based on false premises.

Imagine a couple of friends sitting at a table and playing cards. One of the players notes the order in which the cards are dealt. Then the probability of the cards appearing in exactly that order is calculated. The probability turns out to be so small that the friends could have played cards since the Big Bang without ever being dealt the same card sequence again (Kitcher 2007, p. 93). Nevertheless, the cards were dealt exactly in this order the very first time! This tells us that the a priori probability of the occurrence of any specific event does not tell us whether it actually happened or not. Literally any event can be calculated as improbably as you wish, after the fact. But since it actually happened, the probability of this specific event equals 1. The fallacy of the probability argument is that it presumes the necessity of reaching a pre-specified target. This is not the case.

One could object that every conceivable card sequence would serve the players to continue their game, while in biology only a small fraction of all mutations (of all “deals”) is actually “allowed” or functional. Nonetheless, there is no need to demand pre-specified mutations or pre-defined functions. Instead, there are countless potentially functional mutations, which are completely unknown to us. For example, if every thousandth or only every millionth double mutation has a positive effect under certain conditions, the statement that a specific double mutation occurs with a probability of only 10-20 becomes meaningless. This historically unique event will be just one of an unthinkable number of possibilities to benefit the organism.

So, why does the Discovery Institute keep on overusing the same flawed probability calculations, which correspond to the GIGO concept from computer science (which means: “garbage in, garbage out”), for decades?

Note that there are at least five discrete evolutionary events that must occur in order for T-URF13 to arise: First two sections of DNA … must be brought together by random mutation. But this alone is not sufficient to produce a functional gene. The second step is that the atp 6 promoter must be brought into a position to control the gene. Third, fourth, and fifth: The three binding sites needed for T-URF13 to operate must evolve … Presumably, unless all of these events occur, T-URF13 cannot function to provide any selectable advantage in certain contexts. [McLatchie (2019)]

So what? Again, for two reasons there is no “probabilistic hurdle” at all:

- Behe is wrong in assuming that there are pre-specified target sequences evolution has to “work towards”. There are many completely different sequences that could serve to accomplish a particular function. Even when starting from random sequences, one or two mutations are often sufficient to gain a particular (or a total new) function (Tonkin et al. 2008; De Kraker & Gershenzon 2011; Yona et al 2018).

- The respective mutations have to arise neither simultaneously nor in one single organism. Instead, there is a contemporary, parallel accumulation of random mutations in thousands of individuals which share a gene pool. Then, the different mutations can be combined via sexual recombination in various ways. Such a parallel process tremendously accelerates the evolution of innovations.

Monte Carlo experiments do show that there is a good chance of producing irreducibly complex systems – even if that would require three, four, or even more “matching” mutations at the same time (Trotter et al. 2014). As the authors demonstrate, the evolution of such complex innovations is particularly promising by using genes that are under weak selection pressure like cryptic genes. The number of cryptic genes in a given genome can be rather high. For instance, the proportion of endogenous retroviruses in the human genome alone amounts to at least 8 %. Finlay (2006) speaks of 400,000 insertion points – a huge playing field for evolution!

We summarize that probability calculations against evolution are nonsense since we do not know the entire number of viable variants in the protein space:

A mathematical argument against evolution requires a detailed knowledge of both the probabilistic and geometric structures of protein space (or possibly genotype space, depending on the context). This knowledge is always lacking in practical situation. When you see a probability calculation in some piece of anti-evolution writing, you can be certain that it is based on biologically unrealistic assumptions.” (Rosenhouse 2022, p. 160)

Is the evolutionary explanation a “just-so story”?

The Discovery Institute claims that homology or sequence similarities are “not enough to establish an evolutionary pathway”; Hunt’s mechanistic scenario is a “just-so-story” that did not prove T-URF13 arose through recombinant evolutionary events:

[H]ow does Hunt know that T-URF13 evolved by unguided mutational events from scratch? He doesn’t. Or, at the very least, he has not established that T-URF13 evolved by blind evolution.... If an event is observed to have happened that is highly improbable, having taken into account the available probabilistic resources, that in itself is evidence against the chance hypothesis, and it should drive us to investigate other possible options. [McLatchie (2019)]

This is a very odd argument, since ID proponents always demanded evolutionary (breeding) experiments to falsify the IC argument! The moment they are confronted with such an experiment, they pirouette and demand more. But what more? The evolution of mechanisms at a molecular level is always reconstructed indirectly (by hypothetico-deductive reasoning). Therefore, their demand for “more” is either naive empiricist or an immunization strategy. What do they expect – a microscopic film exposure of how the genes fused together? No one sits in a cell nucleus and watches in real time how mutations happen.

Of course, Hunt was able to show that T-URF13 evolved by recombinant processes during the breeding of certain maize varieties. Crucially, T-URF13 is unique to cms-T maize plants (Von Allmen et al. 1991; Rhoads et al. 1995; Dill et al. 1997; Arun et al. 2011; Yi et al. 2021). No other sources for T-URF13 except the two mitochondrial DNA sequences we will discuss below have been found. Additionally, data exclude exceptional pollen transmission of organelles or multiple horizontal gene transfer events as the source of T-URF13 (Bosacchi et al. 2015).

In other words: If the gene did not just fall out of the blue (and oddly enough, turned out to be identical for 94 % of the ORF* length to pre-existing fragments of the mitochondrial genome), we cannot help but state that it arose (de novo) from available resources.

What other mechanisms than unguided evolutionary processes could be brought into play? Note that the experiments worked exclusively by selective breeding, that is by a Darwinian mechanism. T-URF13 is neither a result of “rational design,” nor of directed evolution. No intentional processes were involved except the selection for pollen sterile variants.

Furthermore, all biochemical mechanisms that are involved in the origination of T-URF13 are well understood.† Hunt (2019) correctly mentioned in his response:

Recombination has been studied for decades, and we know enough about the enzymes to know that the attendant chemical mechanisms are all that are needed to promote the genomic shuffling that gave rise to T-URF13.

Since we are able to identify the homologs of the T-URF13 sequence in the ancestor’s genome, the recombination scenario is currently the only plausible explanation.

Does T-URF13 originate by a “devolutionary process”?

Could one argue that URF13 admittedly evolved but originated from an ancestral pore-forming protein? In that case, the highly specific interdependencies of URF13 would have pre-existed somewhere in the DNA. Therefore, a simple mutation could have restored the receptor gene or altered its activity and specificity. Indeed, the Discovery Institute prefers speculations about a pre-existing gene that became T-URF13 by some so-called devolutionary process – whatever this may mean:

One scenario is that the URF-13 complex is involved in some other process, and that it became broken such that it was no longer properly regulated. Indeed, the first identification of T-URF13 long pre-dates the sequencing of the maize genome in the early 2000s (Chandler and Brendel, 2002; Schnable et al., 2009; Soderlund et al., 2009; Gore et al., 2009; Vielle-Calzada et al. 2009). It thus was impossible to determine whether the T-URF13 gene had indeed arisen de novo ‘from scratch,’ or whether it was already present and doing something else. [McLatchie (2019)]

However, no evidence supports these scenarios. There is no reason in sight to pursue them at all. By now, more than a hundred crop genomes, including mitochondriomes, have been completely sequenced and are available in public databases. There is no gene, there is no sequence resembling T-URF13 except the mentioned 26S rDNA gene (plus the adjacent intergenic region).

In addition, the sequences of thousands of genes coding for rRNA are known from many taxa. Among them is not a single example of any pre-existing protein-coding gene with significant structural similarity to rDNA, with a structure which is even remotely resembling T-URF13. Neither is any example known so far of an exaptation of rDNA-fragments for coding a membrane protein. This is indeed the first one! In distinct contrast to the claims of the Discovery Institute, a scenario that proposes the devolution of a pre-existing protein-coding gene is nothing but a just-so story, not supported by any data.

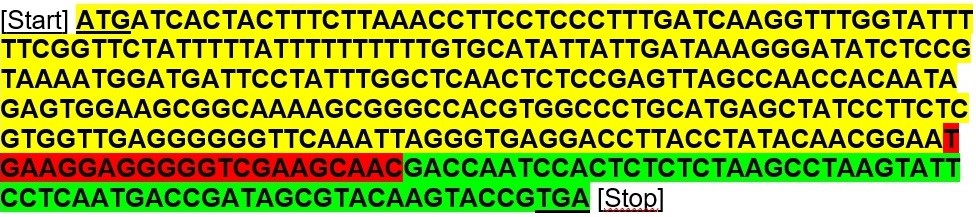

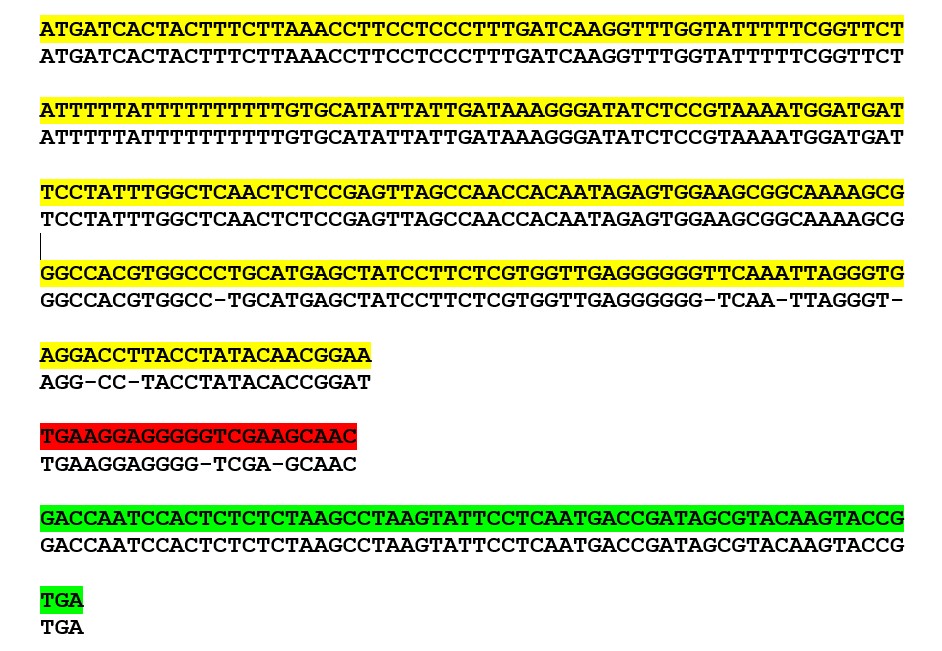

A renewed similarity search (BLAST on May 26 2022, carried out by A.B.) confirmed the result. The origin of the sequences coding for T-URF13 was identified without a trace of doubt: The two major fragments form part of the maize gene for the 26S rRNA and the adjacent non-coding region, respectively. There are no better and more specific search hits than these two perfect hits. Moreover, there is not any other significant hit than those in 26S rDNAs (see the Appendix). Also, in protein databases, there are no significant hits for any part of the URF13 protein apart from URF13 itself.

Is there a “hidden” protein-coding frame inside the 26S rDNA?

As already mentioned, T-URF13 is a chimera of two parts of the mitochondrial chromosome: an intergenic region that is not transcribed and therefore does not code for a protein (yellow), and part of the 26S rDNA gene encoding the 26S rRNA (green). The latter gene is transcribed into RNA but not translated. That means it also does not code for a protein (Pring & Lonsdale 1989).

Moreover, (26S) rDNA encoding for (26S) rRNA molecules does not contain a protein-coding reading frame – and obviously never did. Why do we know this? If one compares the coding regions (ORFs) of protein-coding genes from different species, one repeatedly finds so-called InDels (= insertions or deletions) of 3, 6, 9, etc. bases, that is, integral multiples of 3. On the other hand, if one compares the coding regions of genes that code for functional RNA molecules, particularly the ribosomal RNAs and specifically intergenic regions, one finds InDels that do not comply with the “3-step-rule”.

The biological explanation for this phenomenon is simple: Tiny insertions and deletions usually produce no or little effects in many regions of ribosomal RNAs, in proteins, and especially in intergenic regions. However, InDels containing 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, etc. bases shift the reading frame of an ORF. From the affected point on, the protein is completely changed – and almost always loses its biological function. As a result, such mutations in protein coding parts (ORFs) are negatively selected. Consequently, the fact that rRNAs are not subject to the “3-step-rule” is direct evidence that such rRNAs/rDNA never coded for proteins. Therefore, the present state of knowledge is that the highly specific T-URF13 gene evolved from sequences which never coded for proteins in evolutionary history.

Do deleterious features invalidate the evolutionary argument?

The paper goes to some lengths to explain that URF13 is not a beneficial but a deleterious feature – a “loss-of-function change” – for the domestic plant. However, the conclusion from this fact amounts to an attempt to mislead readers:

It is thus quite telling that, as their flagship example of a new protein complex arising de novo, Arthur Hunt, Nathan Lents, and others choose to promote a system that in fact causes harm to the organism that bears it. Surely if there were a better example — one that is functionally advantageous to the organism — then they would be touting that instead. [McLatchie (2019)]

In fact, this “loss-of-function change” is not a case of structural degradation but a case of structural formation caused by a completely new protein and IC system. Such formative structures occur, under special conditions, also in the wild: As Hunt (2019b) mentions, male sterility is a feature of so-called gynodioecious plants. In gynodioecious plants, females are male sterile, often via mechanisms that recall those that underlie male sterility in cms-T corn. Therefore, such structures can evolve not only by artificial, but also by natural selection. Hunt (2019b): “To claim that this trait causes harm is to badly misunderstand many aspects of plant biology.”

Apart from that, it is impossible to believe that McLatchie does not know that the effect of selective forces does not depend upon a “benefit” in the sense of a quasi-technical optimization, but solely upon a fitness benefit. There is simply no causal link between mutations and mutation mechanisms on the one hand, and the question how selection works on them on the other. There is also no link between the complexity of mutational pathways and the question if the product is beneficial or deleterious. For the discussion of the probability of an event to occur in evolution, it is completely irrelevant if this event might be labeled “advantageous” or “deleterious” in any “technical” sense.

Once again, the question whether a trait can be considered “beneficial” or “harmful” from a functional point of view, is completely independent of the question, how complex it is and how it arose. A machine gun can be considered a harmful tool, surgical instruments as beneficial. That does not mean one is developed easier than the other one. The fact that counts is that URF13 is irreducibly complex.

Does URF13 originate from a signal peptide of Arabidopsis?

The institute’s final contention is a prime example of an argumentative chaos. Below, the argument is quoted in full. Notice, for example, the phrase: “…an insertion of DNA into a pre-existing gene that was itself a membrane protein for mitochondria…” There is a gene that concurrently is a protein? That’s remarkable! Or look at this: “RLF32_ARATH is a signal peptide for import into mitochondria for a gene in Arabidopsis.” Experts know that the plant gene is not imported into mitochondria but rather its product, a protein. But anybody without expertise will become hopelessly confused. Just savor the whole passage:

Proteins embedded in the mitochondrial membrane are synthesized in the cytosol, and therefore they possess an alpha helical a[m]phipathic coil at the N-terminus that is recognized by transport complexes (see this section from the textbook Molecular Biology of the Cell for details). It follows that there ought to be a signal peptide for mitochondrial membrane insertion. That implies that what we have is actually an insertion of DNA into a pre-existing gene that was itself a membrane protein for mitochondria and perhaps a channel — and perhaps a regulated channel since it is affected by nuclear genes. A tool called Signal-BLAST, available at the website of the Center for Applied Molecular Engineering (CAME), allows a user to identify signal peptides in a protein sequence (Frank and Sippl, 2008). Entering the FASTA file for T-URF13 yields a result output of a signal peptide, putative cleavage site after AA 35 (by similarity to RLF32_ARATH). RLF32_ARATH is a signal peptide for import into mitochondria for a gene in Arabidopsis. That protein is involved in cell-cell signaling by way of Ca++ influx. What all this means is that T-URF13 probably came from a fully functional, pre-existing gene, and did not arise de novo. [McLatchie (2019)]

The basic argument, disentangled from the chaos, runs as follows: An analytic tool which allows “high-performance signal peptide prediction based on sequence alignment techniques” shows that the mitochondrial gene T-URF13 contains a sequence similar to one coding a signal peptide in the plant Arabidopsis. The claim is that the peptide is needed to transport a mitochondrial membrane protein which is synthesized in the cytosol (the cell body) into the membrane of mitochondria. That must happen because the gene encoding the mitochondrial protein is located in the cell nucleus. Most of the genes coding mitochondrial proteins indeed are located there. Also, the membrane protein which contains the signal peptide in question forms a regulated ion channel. It is said that it regulates the influx of Ca2+ ions into the mitochondria of Arabidopsis. Therefore, so the argument, T-URF13 could have originated from such an ion channel gene and does not have to be evolved de novo.

We can refute the argument easily. Hunt (2019a), for good reasons, has rated it as “jaw-droppingly bad.”‡ For one thing, the T-URF13 gene is located not in the nucleus but in the mitochondrial genome. Thus, no import into mitochondria happens, neither for URF13 protein nor for T-URF13. That is simply a matter of fact. There is no trace of T-URF13 or anything similar in the nuclear genome. So why should a hypothetical predecessor gene code for a signal peptide which transfers cytosol proteins from outside into the mitochondrial membrane? That simply makes no sense.

Secondly, the claim that the analytic tool detects a gene sequence similar to that coding for a signal peptide known from Arabidopsis thaliana is dubious. The match is incomplete at best. Strangely enough, the particular A. thaliana protein, to which the signal peptide in question belongs, is not transported into mitochondria but into the plasma membrane, so there is something seriously wrong with the whole claim.

Thirdly, there is no significant match between this protein family and URF13. There is even no remotely significant match with any protein in the whole protein database (Protein BLAST @ NCBI: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins). Obviously, whatever the Arabidopsis genes are and do, there is no evolutionary connection to T-URF13. But only experts in molecular genetics realize that the so-called data are fabricated. Everybody else is overwhelmed by the maze of technical jargon. That is the Discovery Institute’s strategy.

Literature

Arun, V. et al. (2011) Transformation and analysis of tobacco plant var Petit havana with T-urf13 gene under anther-specific TA29 promoter. 3 Biotech 1, 73–82.

Behe, M. (1996) Darwin’s black box: The biochemical challenge to evolution. The Free Press.

Bosacchi, M.; Gurdon, C. & Maliga, P. (2015) Plastid genotyping reveals uniformity of cms-T maize cytoplasms. Plant Physiology 169, 2129–2137.

Braun, C.J.; Siedow, J.N.; Williams, M.E. et al. (1989) Mutations in the maize mitochondrial T-urf13 gene eliminate sensitivity to a fungal pathotoxin. PNAS 86, 4435–4439.

De Kraker, J.-W. & Gershenzon, J. (2011) From amino acid to glucosinolate biosynthesis: Protein sequence changes in the evolution of methylthioalkylmalate synthase in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 23, 38–53.

Dill, C.L.; Wise, R.P. & Schnable, P.S. (1997) Rf8 and Rf* mediate unique T-urf13-transcript accumulation, revealing a conserved motif associated with RNA processing and restoration of pollen fertility in T-cytoplasm maize. Genetics 147, 1367–1379.

Finlay, G. (2006) Human genetics and the image of God. http://www.cis.org.uk/ireland/documents/God&Science_Paper2_Finlay.pdf

Hunt, A. (2007) On the evolution of Irreducible Complexity. https://pandasthumb.org/archives/2007/05/on-the-evolutio-1.html

Hunt, A. (2019a) T-URF13 and devolution. https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/T-URF13-and-devolution/5696

Hunt, A. (2019b) Where gynodioecy is cast out of God’s creation https://discourse.peacefulscience.org/t/where-gynodioecy-is-cast-out-of-god-s-creation/5651

Kanzaki, H.; Takeda, M. & Kameya, T. (1991) Sequence analysis of a mitochondrial DNA fragment isolated from cultured cells of carrot cytoplasmic male-sterile strain. The Japanese Journal of Genetics 66, 719–724. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjg/66/6/66_6_719/_article

Kitcher, P. (2007) Living with Darwin. Evolution, design, and the future of faith. Oxford University Press.

Lents, N.H. (2019) Behe’s last stand: the lion of Intelligent Design roars again. https://www.skeptic.com/reading_room/michael-behes-last-stand-lion-of-intelligent-design-roars-again/

Levings 3rd, C.S. (1990) The Texas cytoplasm of maize: cytoplasmic male sterility and disease susceptibility. Science 250, 942–947.

McLatchie, J. (2019) Does T-URF13 Refute Irreducible Complexity? A Response to Arthur Hunt. https://evolutionnews.org/2019/04/does-T-URF13-refute-irreducible-complexity-a-response-to-arthur-hunt/

Pring, R.D. & Lonsdale M. (1989) Cytoplasmic male sterility and maternal inheritance of disease susceptibility in maize. Annual Review of Phytopathology 27, 483–502.

Rhoads, D.M.; Levings 3rd, C.S. & Siedow, J.N. (1995) URF13, a ligand-gated, pore-forming receptor for T-toxin in the inner membrane of cms-T mitochondria. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes 27, 437–445.

Rosenhouse, J. (2022) The failures of mathematical anti-evolutionism. Cambridge University Press.

Tonkin, C.J.; Foth, B.J.; Ralph, S.A. et al. (2008) Evolution of malaria parasite plastid targeting sequences. PNAS 105, 4781–4785.

Trotter, M.V.; Weissman, D.B.; Peterson, G.I.; Peck, K.M. & Masel, J. (2014) Cryptic genetic variation can make “Irreducible Complexity” a common mode of adaptation in sexual populations. Evolution 68, S. 3357–3367.

von Allmen, J.-M.; Rothmann, W.H.; Gengenbach, B.G. et al. (1991) Transfer of methomyl and HmT-toxin sensitivity from T-cytoplasm maize to tobacco. Molecular & General Genetics 229, 405–412.

Yi, H. et al. (2021) Identification and genetic analysis of two maize CMS-T mutants obtained from out-space-flighted seeds. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 68, 1–11.

Yona, A.H.; Alm, E.J. & Gore, J. (2018) Random sequences rapidly evolve into de novo promoters. Nature Communications 9, 1530.

Appendix: The mysterious PKT5 “gene”

Indeed, a recent BLAST search corroborated the notion that T-URF13 had been composed of two fragments of the mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) of maize. The yellow and the green region (Fig. 3) perfectly match to other parts of the mtDNA as described. The red part finds no match in the maize nuclear genome or mitogenome corroborating the notion that this part has been created by mitochondrial DNA double strand repair. The shortness of this part further supports that idea. Furthermore there are quite a few nearly perfect matches simply by chance in very different organisms – as to be expected by the shortness of this part.

There is, however, a very surprising full-length match with a gene in a male-sterile lineage of carrot Daucus carota (Fig. 5). Kanzaki et al. (1991) named it PKT5 gene. Their paper seems to suggest that very similar (in fact: identical) rearrangements took place independently in maize and carrots to produce male-sterile lines and a full-length match with T-URF13. Since this is not a particularly satisfying explanation, how can this be conundrum be explained? Some facts will help:

- The alignment contains only two mismatches, but beyond that eight (!) single-base deletions – all of them in D. carota PKT5. However, mismatch mutations occur 4 to 10 times more frequent than insertions or deletions. Moreover, they should have occurred in both genes at about the same rate. Here, however, the green and yellow parts of T-URF13 match perfectly to maize mitochondrial DNA, whereas all mismatches occur in the carrot “gene”. Such characteristics are typical for sequencing errors. This is further substantiated by the fact that all of those deletions would destroy almost half of the open reading frame creating a substantially changed protein, which surely cannot work like URF13 protein.

- The similarity of D. carota PKT5 to maize mtDNA is almost perfect on the one hand. On the other hand, its similarity to D. carota mtDNA is much weaker as easily can be seen in BLAST search. How should a carrot gene arise from maize mitochondrial genome? The only possibility would be horizontal gene transfer which is also not convincing since there is no further evidence.

- The experimental approach of Kanzaki et al. is questionable since their hybridisation experiment does not make sense: T-URF13 has been assembled from maize mitochondrial genome and shows – except for the red part – perfect sequence identity. So, it will hybridise to any mitochondrial genome with sufficient sequence similarity. So why even try

- To corroborate the mere existence of carrot PKT5 gene, the presence of the coded protein has to be demonstrated. To our knowledge, this has not happened so far.

This all does not make any sense. By the way: It also does not fit into a design scenario (unless you would like to argue: “The Designer in his unfathomable will can do whatever he/she/it wants”). Such patterns, however, are typical of artefacts produced experimentally: mix-up of clones and sequencing errors, which in most cases are never cured in the databases. First author (A.B.) experienced such cases during his time in the human genome project – to mention only three examples:

- At that time, a significant portion of clones from cDNA and gDNA libraries were interchanged (meaning the accession or ordering number was assigned to a wrong clone).

- During assembly of chromosomes from reads always some sequences fall out of the alignments for a simple reason. They originated from different species and erroneously were inserted into the processing pipeline.

- Erroneous sequences produced either by PCR/cloning artefacts or by low quality sequence runs.

Nowadays, LIMS (Laboratory information management systems) have reduced such errors by some orders of magnitude. The respective paper (Kanzaki et al.), however, is from 1991, when such systems did not exist or were in their infancy. It fits well into this scenario that the authors were provided with a cloned version of T-URF13.

In short: Obviously, the carrot PKT5 gene simply does not exist.

* ORF (Open Reading Frame) is the protein-coding region of a gene.

†They even explain the origin of the red marked intermediate area illustrated in Fig. 3 and 4: When mismatched ends are assembled (via non-homologous double strand break repair mechanisms), the sequence at the junction often changes rather randomly. That is why no significant homologs are found in the databases for this area.

‡Further pseudo-arguments against the T-URF13 example presented by the “Uncommon Descent” guys are debunked by Hunt: https://www.ag-evolutionsbiologie.net/html/2019/T-URF13.html

You may find a pdf version of this paper here

About the authors. Prof. Dr. Andreas Beyer studied biology at the Ruhr University in Bochum (Germany) with a focus on biochemistry, physiology, cytology and microbiology. Doctorate on the topic “molecular biological characterization of the AAA gene family, a new group of putative ATPases”. Research on the phosphorylation of phosphorylase kinase at the Institute for Physiological Chemistry at the Ruhr University. Applied research in various industrial projects. Lecturer at the Westfälische Hochschule Gelsenkirchen, Bocholt, Recklinghausen (Germany) as Professor of Molecular Biology. Chairman of the working group “AG Evolutionsbiologie” which is associated with the German Association of Biologists (VBio).

Dr. Hansjörg Hemminger received his postdoctoral qualification as a university teacher of behavioral biology (Habilitation) from the University of Freiburg (Germany). He was commissioner for world view questions, especially for the dialogue between science and religion, in the Protestant Church until retirement. As an expert member of a parliament commission (Bundestag) he investigated fanatic and sectarian forms of religion. He published numerous articles and books in German and English.

Martin Neukamm is a German chemist and managing editor of the “AG Evolutionsbiologie” (www.ag-evolutionsbiologie.de), a German scientific association that deals with evolutionary biology and creationism. He has published various articles and books on evolution and creationism in the German language.

Acknowledgement. Arthur G. Hunt, Professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Kentucky, very kindly read and commented on a draft of this paper. Matt Young will be the moderator of this thread. Copyright © 2022 by AG EvoBio, all rights reserved.