Meditation on “The Snowflake: Winter's Frozen Artistry”

Almost literally, as I was finishing the book The Snowflake: Winter’s Frozen Artistry, by Kenneth Libbrecht and Rachel Wing, I heard this report on NPR: Professor Libbrecht had discovered and photographed what, as far as anyone knows, is the largest single-crystal snowflake ever discovered – approximately 10 mm across. The snowflake was evidently larger than the field of view of Prof Libbrecht’s microscope and had to be photographed in 4 quadrants, which were later digitally stitched together. The snowflake has been accepted in the Guinness Book of World Records.

As for the book by Libbrecht and Wing, it is short, wastes hardly a word, and was a pleasure to read. It is not a technical book, nor is it a children’s book, yet I kept thinking that much of the early chapters would be an excellent way to stimulate an interest in science in, say, medium-sized children. As of this writing, you may get the Kindle edition of the book for approximately $3, US. I read it on a Kindle Paperwhite, which gives a small, black-and-white image, so I had to look at some of the images on a computer monitor in order to get full color and resolution. The formatting on the Kindle was not wonderful, but it was manageable. More below the fold.

I have always wondered why the arms of a snowflake, which Libbrecht and Wing call a stellar dendrite, are identical or nearly so. Of course, they are not always identical but why are they ever identical? Libbrecht and Wing explain succinctly that under some conditions ice forms hexagonal structures (or at least corners of hexagonal structures) and under other conditions, branching arms. As conditions change and the snowflake encounters different temperature and humidity regimes, it alternately grows smooth, flat surfaces, or facets, and branches. By stunting their growth, the facets stabilize the otherwise unstable branches. At least sometimes, the conditions are constant across the snowflake, and over a period of minutes it evolves 6 identical arms.

The scientifically inclined may find the chapter, “A field guide to falling snow,” especially interesting. In that chapter, we learn that, besides snowflakes, water sometimes crystallizes into hexagonal plates, needles, or hexagonal cylinders. These contribute to many atmospheric effects such as sun dogs and halos. In addition, however, they sometimes form capped columns, which look like microscopic dumbbells, and even 12-branched stars. The chapter concludes with frost, rime snow, and even a picture of a dendrite coated with rime snow. Children of all ages will learn how to fossilize a snowflake in superglue.

I was particularly intrigued by Nakaya’s snow crystal morphology diagram. Not exactly a graph, this diagram shows pictures of different kinds of ice crystal on a Cartesian plot with humidity on the vertical axis and temperature on the horizontal axis. Not surprisingly, we get plates and cylinders when the humidity is low and dendrites when the humidity is high. I found it curious that dendrites form just below freezing and well below freezing, but not between. Later in the book, Libbrecht and Wing inform us that this behavior remains a mystery.

If I have one quibble, it concerns the construction of the microscope. They use what appears to be a conventional microscope turret and a digital camera, but it is unclear whether the lens has been removed from the digital camera. With the right microscope objectives, you could do it either way. Some of the pictures, incidentally, are taken using something called Rheinberg illumination, which is evidently oblique illumination using different colors simultaneously. I am supposed to know something about microscopy, but I will have to look that up right after I finish this article.

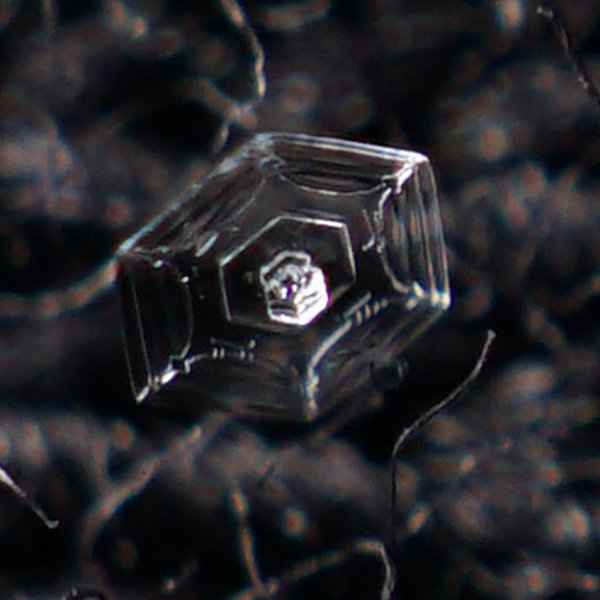

I first heard of Prof. Libbrecht in 2016, when he was featured in an article in the New York Times. Under carefully controlled conditions, he had grown pairs of identical snowflakes, thus in a sense demonstrating the falsity of the claim that no two snowflakes are identical. He very generously let us post a pair of twins on PT in 2017. It is interesting how the snowflakes freeze water vapor from the air and clear themselves a region that is free of the frozen droplets that cover the rest of the microscope slide.

OK, I cannot resist, and I hope you will indulge me: Last year, at the very end of the season, I took a fairly fuzzy black cloth out into a cold, light snow flurry, let it chill for a while, and allowed some snowflakes to fall on it. The fuzz was to prevent the flake from landing on the cloth itself and potentially melting. I photographed some snowflakes with a handheld Sony ILCE 6000 with a 30-mm macro lens and the built-in flash (possibly with a diffuser, but I do not remember). Using some digital image processing software, I could easily crop the picture and end up with a picture of a snowflake around 600 pixels square. Not exactly the same quality as Libbrecht and Wing’s, but it could have been worse. Next time I will know enough to stretch the cloth tightly (because of the severely limited depth of field) and will probably use a short extension tube.

Sure enough, I found a handful of hexagonal plates, which I now know could have been the seed for a single-crystal snowflake.

I also fooled with some frost on a window, which (I know now) grows very differently from a snowflake and probably follows the contours of what I will call shmear on the glass.

For more, I recommend that you get the book and in your own small way help support Prof. Libbrecht’s research at Caltech. As he says, “Really, it’s the perfect gift.”