Aphantasia and me

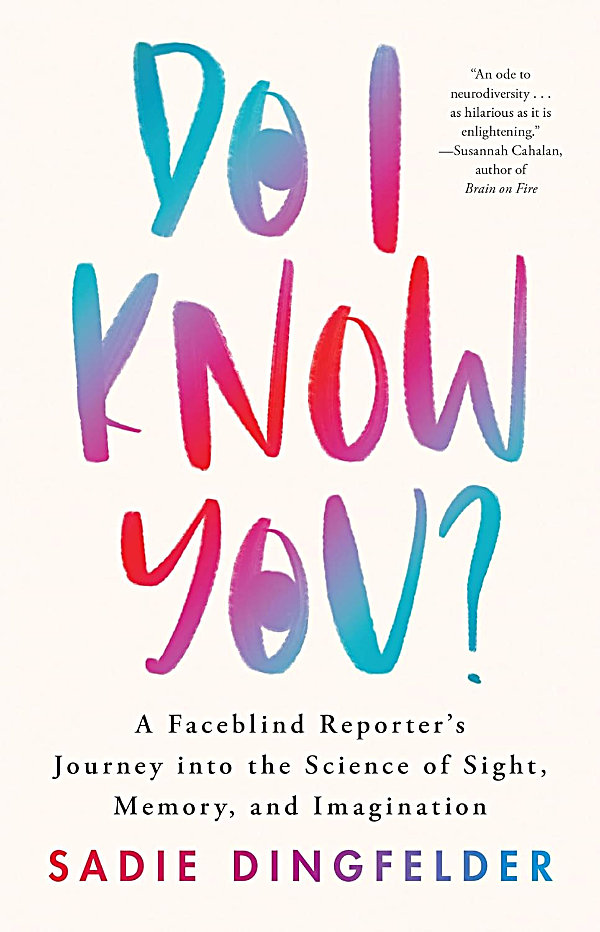

Who knew? I have aphantasia, the inability to visualize things. Well, probably not fully fledged aphantasia, but certainly dysphantasia. Aphantasia is a word I first learned on listening to an NPR program with a somewhat lengthy title, The human brain is hardwired to recognize faces. But what if you can’t? It turns out that Sadie Dingfelder, the author of the book Do I Know You? A Faceblind Reporter’s Journey into the Science of Sight, Memory, and Imagination, can’t. Recognize faces, that is.

Ms. Dingfelder is not only face blind; she is also stereo blind and aphantasic. Now, I understand that freshman psychology students think they suffer from every affliction they study, but I was surprised to find that I have some degree of all of those.

I was stereo blind until a dozen or two years ago. Indeed, I remember commenting to the eminent lens designer Rudolf Kingslake that I saw no difference between one eye and two. He was astonished and told me everything popped into life with two eyes open. I in turn was baffled. (I must have had some stereopsis, because I found that, when I looked at a painting or photograph with one eye, I saw more depth than with two eyes, presumably because the clue that the painting was flat was missing without the stereopsis afforded by two eyes. This technique, which was taught to me by a photogrammetrist at the University of Guelph, is very useful when walking around art galleries.) Many years later, while engaging in eye exercises for something else, I suddenly developed what I think may be fairly good stereo vision, and it has never gone away, even after I quit the exercises.

I suspect that I first learned of face blindness, or prosopagnosia, from Oliver Sacks’s book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. According to the NPR report, Ms. Dingfelder is almost completely face blind, more so than almost anyone else. After reading Sacks’s book, I realized that I too have a degree of face blindness – I suppose I could say prosopdysgnosia, but that would be a dreadful word. At any rate, although I have never accused anyone else’s spouse of buying junk food, as did Ms. Dingfelder, I have a lot of trouble recognizing people I have just met or know only slightly.

As for aphantasia, I can visualize things but not well. Possibly that is one reason I do not like fiction that is heavy with description. The apple I am visualizing right now is merely a hollow, transparent shell. I can see the stem, the black sepals at the blossom end, and the core, but the skin has no color, and the flesh has no texture, if it exists at all. I think probably this inability to visualize is why I cannot draw objects with curves very well, and faces are out of the question.

According to Kirkus Reviews, Ms. Dingfelder has amblyopia, or lazy eye, which I presume is the origin of her stereo blindness (unless, of course, it is the other way around). Kirkus says that as a result of her stereo blindness she cannot get around easily, walk on uneven surfaces, or drive a car. Either Ms. Dingfelder or Kirkus partly misunderstands depth perception. We have depth perception even with one eye; it is just not as good as stereo vision. In Colorado, for example, you may drive as long as your vision in one eye is 20/40 or better.

It sounds as if the book is part memoir and part science, rather like this essay. I have not yet read it, but I intend to do so as soon as I can manage it.

Appendix 1. An appendix is a vestigial part of a document and has no known function.

Appendix 2. While writing this essay, I was reminded of an anecdote told to our class by my philosophy professor, Murray Turbayne. Professor Turbayne relates asking his mother-in-law to visualize an apple. I forget the exact order, but, roughly, he asks her to imagine that it has no color. OK, no color. No smell or taste. OK. No weight. OK. No texture. A little harder, but OK. What is left? The apple! We then had a discussion, which I only dimly remember, about whether the apple was more than the sum of its attributes.