Knowing you are right, even when you are not

This little book, On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You’re Not, is not exactly about epistemology, that is, how we know what we know; rather, it is about how we think we know, even when potentially we do not. Indeed, it seems to me that it explains why the philosopher Lee McIntyre was by his own account singularly unsuccessful in convincing virtually any science denier about anything (see my article here).

The author of the present book, Robert Alan Burton, is a neurologist, not a philosopher. The book was originally published in 2009 and recently rereleased. It is well out of my area, so I have no way of knowing how much is dated. To oversimplify, Burton argues, somewhat apologetically, that there may be evolutionary advantage to having a module that quickly tells you, you are right. As he notes in the Preface,

Despite how certainty feels, it is neither a conscious choice nor even a thought process. Certainty and similar states of “knowing what we know” arise out of involuntary brain mechanisms that, like love or anger, function independently of reason.

He calls this sentence “[t]he revolutionary premise at the heart of this book….”

Another oversimplification (mine, that is): Burton tells us that the brain is a neural network (or perhaps a network of neural networks) that can be characterized as having an input, an output, and between them a hidden layer that does all the processing. We know that the layer is hidden, in part because we can bring to the surface only one or two of our thought processes at a time. Other thought processes are clearly going on, as we know, for example, when we have a sudden realization of something that we did not consciously know we were thinking about. Suddenly, we just know the solution to an important problem; we have what Burton calls a feeling of knowing, and he considers this phrase so important that he italicizes it throughout the book.

This insight, that we have a feeling of knowing whether we know or not, is important to discussions of pseudoscience. In my article on McIntyre’s book On Being Certain (see link above), we met flat-earthers who could not be disabused of what we consider their delusions. Relevantly to PT, Burton hauls out the creationist Kurt Wise, who has a BA degree in geophysics from the University of Chicago, an MA degree in geology from Harvard, and a PhD in paleontology under no less a personage than Stephen Jay Gould. He is now director of the Creation Research Center at Truett McConnell University in Georgia. For all that, Wikipedia quotes him as saying,

Although there are scientific reasons for accepting a young Earth, I am a young age [sic] creationist because that is my understanding of the Scripture. As I shared with my professors years ago when I was in college, if all the evidence in the universe turns against creationism, I would be the first to admit it, but I would still be a creationist because that is what the Word of God seems to indicate.

Wise is now director of the Creation Research Center at a Baptist institution, Truett McConnell University in Georgia.

At least Wise has the humility to use the qualifier “seems to indicate.” Richard Dawkins, as Barton describes him, seems absolutely sure of himself:

Faith is the great cop-out, the great excuse to evade the need to think and evaluate evidence. Faith is belief in spite of, even perhaps because of, the lack of evidence.

And

I will respect your views if you can justify them. But if you justify your views only by saying you have faith in them, I shall not respect them.

Though I am far more sympathetic to Dawkins than to Wise, I fear that Dawkins has succumbed to the feeling of knowing and assumes that his thoughts are purely rational. Burton argues to the contrary, that your thoughts are shaped by your past and the structure of your brain. The disembodied rational mind, he says, does not exist. Both Dawkins and Wise have the feeling of knowing, and Dawkins is downright evangelical in his need to propagate his atheism.

Lest you get the wrong idea, Barton is not a nihilist and clearly sees the need for evidence. He takes the physician Andrew Weil to task for refusing to believe a null result, instead saying,

We were unable in those tests to prove that this had an effect. The problem is, I’m sure there’s an effect there.

I was reminded of Richard Feynman’s famous quotation, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.” At any rate, you do not need a disembodied rational mind to know that if you do an experiment properly you ought to accept the results. As Barton notes,

The failures of science … begin with personal self-deception and an unjustified sense of knowing. … "I am sure" is a mental sensation, not a testable conclusion.

I will not go into detail, but besides Weil and Dawkins, Barton subjects to scrutiny Russell Targ, Paul Davies, Leon Kass, Francis Collins, Richard Lewontin, Daniel Dennett, Stephen Jay Gould, Stephen Hawking, and Malcolm Gladwell. Some of them fare better than others.

I will conclude, as does Barton, with a speculation as to whether

some of the toughest age-old philosophical issues arise out of attempts to resolve perceptual tricks created by our brains.

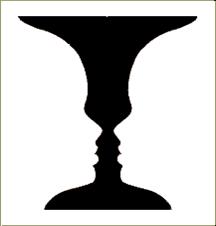

Barton notes the famous “optical illusion of the silhouette of two opposing faces that can also be seen as a vase.” I think virtually everyone knows this illusion, Rubin’s vase, pictured at left, so Barton does not see a need to show it. When you look at the picture one way, you see a vase; when you look at it another way, you see two opposing faces in profile. Evidently it is not possible to see both at once. Barton wonders whether mind-body dualism, for example, or our inability to understand whether time or space begins or is infinite, is roughly equivalent to our inability to view Rubin’s vase as both two faces and a vase at the same time.

Completely off-task: The discussion made me wonder about wave-particle duality. Very roughly, if we perform a diffraction experiment with a phosphorescent screen, a photon will propagate through space as if it were a wave but react with the screen as if it were a particle. Presumably it is something much more complicated than either a wave or a particle, something that is occasionally called a wavicle. Is it possible that the perceived duality is no more than our inability to perceive both aspects, wave and particle, simultaneously, a sort of physical Rubin’s vase?