Lions, elephants and cheetahs (in America?) Oh, my!

Coming soon to Nebraska?

Coming soon to Nebraska?

In the August 18th issue of Nature (1), Donlan et al. suggest a novel way to save certain species of megafauna: bring them to the North American wilderness. (CNN summary/commentary here).

It’s not as outlandish as it may sound. As they point out, North America had many similar species until 13,000 years ago, including mammoths, camels, cheetahs, and lions. While they acknowledge there are differences between modern species and those which existed once upon a time in America, they suggest that the modern species are proxies for their long-extinct cousins, and could be used to “re-wild” North America. The authors suggest a mutually beneficial relationship: portions of the Great Plains benefit from tourism dollars, while the animals benefit from increased habitat and a decreased threat of extinction. Win-win, right?

Potential pitfalls are mentioned. In addition to the “they’re not exactly the same” objection mentioned above, the authors mention other likely criticisms: disease, different habitats, and “unexpected ecological and social consequences of reintroductions.” They suggest moving animals onto large tracts of private land in order to study these possibilities prior to the final stage in their vision: “ecological history parks,” with perimeter fencing, allowing these large mammals to roam free over large stretches of the Great Plains. While I applaud their optimism and their passion, and while I’d love to be able to drive a few hundred miles and see animals like this in “the wild,” our history of moving animals around the world just ain’t that great, and often has unintended consequences.

First, “unexpected consequences.” The authors highlight the successful re-introduction of peregrine falcons in North America as a recent example of “proxy species” used to replace an extinct population. Indeed, 2500 captive-produced birds (Falco peregrinus) were released in the east beginning in 1974, and in the Midwest beginning in 1982 (2), and appear to have flourished. However, the time scales between elimination of the original population of peregrine falcons and re-introduction of new ones in comparison to the megafauna re-introduction differ by a factor of over 400. The decimation of the falcon population began in the late 1940s as a result of chlorinated hydrocarbon poisoning, and severe effects were seen by the mid-1960s. If we’re generous, we can say that a span of 30 years went by between the elimination of the bulk of the peregrine falcon population and the re-introduction of their cousins of different subspecies. In the case of the re-introduction of these large vertebrates, the time span is over 10,000 years; not a valid comparison, in my mind.

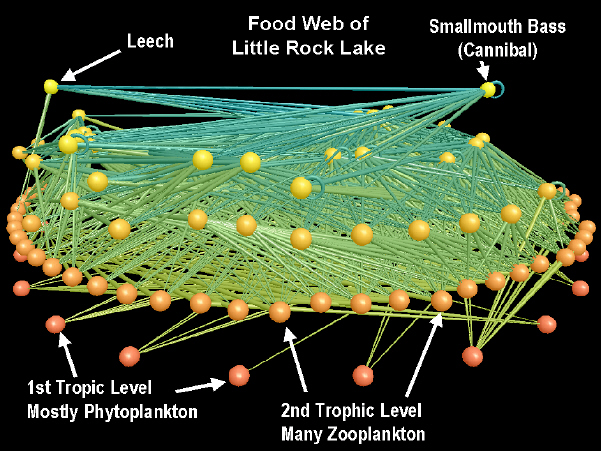

Additionally, our success with introductions of novel species into new areas has not exactly been high. One suggestion is that these animals will serve to control the “pests and weeds” that dominate the Great Plains landscape. Perhaps elephants can eat certain plants that threaten grasslands. This brings to mind other biological control agents—such as the cane toad in Australia , which were not only unsuccessful, but by most accounts, an environmental disaster. Granted, elephants are quite a bit easier to keep track of than toads, but ecological webs are tricky, and it’s difficult to predict what long-term effects the introduction of a new species will bring. Let me provide a graphic example. This is taken from the webpage of Mark Newman, a physicist at the University of Michigan who works with all different kinds of complex systems.

Don’t focus on the specific examples; the key is to see how inter-connected all of the individual species (the “hubs” or dots) are. (Another good example, with some more commentary, can be found here. ) When one hub is disturbed, it may have severe effects on the interactions at other levels. There’s a great chapter on this in Mark Buchanan’s book Nexus: Small Worlds and the Groundbreaking Science of Networks. (3) Buchanan quotes ecologist Kevin McCann (4):

The lessons for conservation are obvious: 1) if we wish to preserve an ecosystem and its component species then we are best to proceed as if each species is sacred; and 2) species removals (that is, extinction) or species additions (that is, invasions) can, and eventually will, invoke major shifts in community structure and dynamics.

The question then becomes—which is more important: maintaining the ecosystem of the Great Plains by preventing invasion of non-native species, or acting to prevent extinction of these large vertebrates, something which certainly is a concern to many ecologists? While I think overall this is a bad idea, I don’t have any concrete answers, and at least it’s heartening that the suggested plan is (supposedly) to proceed slowly.

My other concern is one Donlan mentions but glosses over: disease transmission. I’m a microbiologist, and my emphasis area is infectious disease epidemiology. Additionally, a major focus of the research center I’m involved with just happens to be zoonotic disease: disease which is transmitted between different animal species. So my first thought is, “what biological agents will these introduced species bring along with them?” And secondarily, “what biological agents will they encounter here, that they’ve not encountered in their native lands?” Certainly some of this has been experienced already, as these animals are present in zoos, circuses, and private refuges throughout the country, but there’s a difference in disease potential between animals housed in contained areas with regular medical care, and those roaming free in the wilderness, able to be in contact with a large variety of other species who’ve not been vaccinated and are not routinely screened for disease. A figure of 77,000 “large mammals” which “roam free” on Texas ranches is mentioned in the article; I’d love to see more data about these as they go forward with their idea. I’d hate to see some kind of pathogen native to elephants spread into, say, the wild deer population, and then spread to hunters, and then further into the human population, for example. Alternatively, it would be horrible to have a mass die-off of elephants due to an infection native wildlife have immunity against, and carry asymptomatically.

In the end, if this is carried out on private land, I’m not sure what could be done to stop them. I know some areas have laws against housing wild animals; I suppose other areas could impose them if it seems this is going forward faster than local authorities may like. But given the political climate of the United States, it seems that the enticement money brings often trumps the science that may support or derail such ideas. Donlan’s last thought in the Nature article states that they “…want to reinvigorate wild places, as widely and rapidly as is prudently possible.” As much as I’d love to take my kids on an “African” safari just a few hundred miles away, I hope prudence is more important than speed.

References:

(1) Donlan, J. Re-wilding North America. Nature. 2005 436:913-4. (2) Tordoff, H.B.; Redig, P.T. Role of genetic background in the success of reintroduced Peregrine falcons. Conserv. Biol. 2001 15:528-32. (3) Buchanan, M. Nexus: Small worlds and the groundbreaking science of networks. W.W. Norton and Company: New York. 2002. (4) McCann, K.S. The diversity-stability debate. Nature. 2000 405:228-233.