Another example of "scholarship"

With the recent resounding defeat of Intelligent Design in Dover, ID supporters may actually have to try and do some science to support their claims. On the basis of past efforts, the prospect does not look good for them. Richard von Sternberg, the Intelligent Design-friendly editor who was responsible for publishing Meyer’s woeful review paper, has recently had a paper published with anti-Darwinian James Shapiro (who has said he is not an ID supporter).

In this they try to address the bete noir of creationists, both young earth and intelligent design varieties, “Junk” DNA. The fact that the vast majority of the genome is probably parasitic junk is hard to reconcile with an intelligent designer, so a lot of effort is expended to show that all that DNA must be doing something essential. Sternberg and Shapiro try to show that one major class of non-coding DNA, highly repetitive DNA, is essential for genome function. However, all they end up demonstrating is shoddy scholarship.

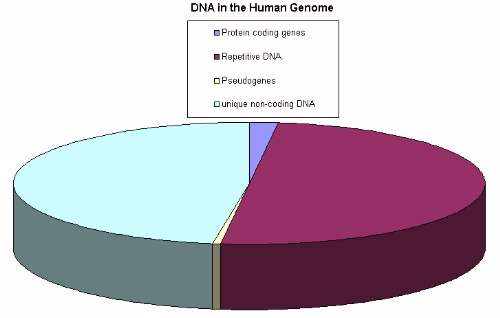

One of the fruits of the genomic revolution is the finding that the majority of most eukaryote genomes don’t code for proteins. In humans, only around 1-2% of our DNA codes for proteins. The remainder consists of genes for ribosomal RNA, small regulatory RNAs of various types, regulatory elements, broken genes (including defunct viral genes incorporated into our DNA), the spacers that exist within genes, a whole lot of intergene material and lots of repetitive sequences. The regulatory elements (stretches of DNA where proteins can bind to change gene expression, stretches of DNA that code for small RNA’s that can modify gene expression etc.) are critical for co-ordinating gene expression during development and during adulthood. We need these as much as we need protein coding genes, but overall it is broadly estimated that that only about 3-5% of the non-coding genome is involved in regulation (Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2002). So what is the rest doing?

Overall, not a lot. The general consensus is that the majority of the non-coding, non-regulatory DNA is functionless (the so called “junk DNA”). Some might have a strictly structural role (where you need x bases of DNA, any kind of DNA, to support the structure of the chromosome, this role is sequence independent), but overall the vast bulk of DNA is without function. There are a number of reasons to believe this, but I will talk about some of this evidence later. Roughly 50% of DNA is what is called repetitive DNA, a sort of molecular stutter. In general (but there are exceptions), a large proportion of this is seen as “selfish” or “parasitic” DNA. The majority of this repetitive DNA is made up of transposable elements. Long interspersed elements (LINES) make up 21% of the human genome, and some code for genes that allow them to make copies of themselves. Short interspersed elements (SINES) make up about 11% of human DNA and require active LINES in order to be copied. Now, it is almost certain that a small proportion of LINES and SINES has been co-opted to do something useful in the genome, about 0.1% of SINES may be involved in alternative splicing of genes. However, as it currently stands the vast majority of these elements don’t seem to do anything useful.

Now, as I said, there are a number of reasons why biologists think that the majority of non-coding DNA is non-functional. However, the idea that the bulk of the genome does nothing is seriously worrying to Young Earth and Intelligent Design creationists. The paper by Shapiro and von Sternberg tries to claim that the repetitive DNA in our genomes is essential. It consists of large amounts of hand waving, some out-of-context quotation and trying to shoehorn the expression of the genome into a computer file metaphor. I won’t go into the entire paper in detail, but I will look at one example that demonstrates the shoddiness of the “scholarship” in this paper.

One of the challenges to the idea that the majority of non-coding DNA is doing something useful is the existence of organisms like the puffer fish Fugu. Despite being a fairly complex vertebrate, with roughly similar number of genes to humans, it has between half to one-third the non-coding DNA that other vertebrates (and non-vertebrates) have. So what do Shapiro and von Sternberg say about Fugu? Their only mention is this:

“Rapidly reproducing organisms, like Caenorhabditis, Drosophila, Fugu and Arabidopsis, tend to have stripped-down genomes with relatively less abundant repetitive DNA, while organisms with longer life cycles, such as humans and maize, have larger genomes with correspondingly more repetitive elements (Table 1).”

However, their own table shows that this is nonsense.

In order of reproductive rate

| Organism | % Genome repetitive DNA | Reproduction rate |

| Caenorhabditis briggsae | 22% | approx 25-50 times per year |

| Drosophila (fuit fly) | 34-57%* | 6-12 times per year |

| Clionia(tunicate) | 35% | several times to once per year |

| Mouse | 40% | 3-4 times a year |

| Fugu | 15% | Once per year |

| Dog | 31% | Once per year+ |

* In male Drosophila the Y chomosome is mostly repetitive DNA. + Some dogs can potentially reproduce twice a year. Clionia reproduction can range from continuos release of spawn to once per year, depending on latitude. Fugu has a broad spawing period of about 2 months, but it takes about a year to go from from fertilization to sexual maturity. Fugu has less repetitive DNA than the microscopic worm Caenorhabditis briggsae, which reproduces every week.

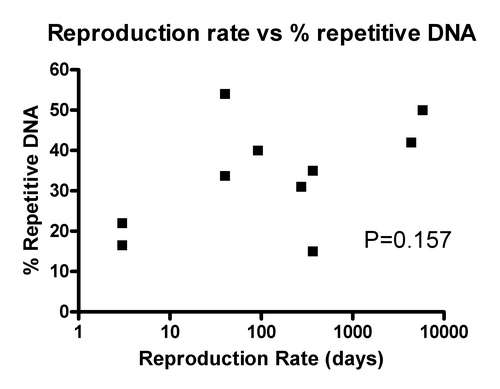

As you can see, from their own table (I’ve added in the reproduction rates to make this clear) the amount of repetitive DNA is not correlated with reproduction rate. I’ve actually done the statistics on this. You can look at either time to reproductive maturity, or interval between successive broods, but either way there is no correlation between amount of repetitive DNA and reproduction ate (P > 0.1 and 0.3 respectively).

In bacteria, there is very little repetitive DNA, this is thought to be due to their fast reproduction rate (hours to days). But Fugu reproduces relatively slowly, certainly slower than mice and Drosophila, yet it has far less repetitive DNA than them. The upshot is that Fugu, a reasonably complex vertebrate with about as many protein coding genes as humans, and more than Drosophila, gets by with half to one third of the repetitive DNA most complex metazoans have, suggesting these sequences are not essential. However, Shapiro and von Sternberg hand wave the Fugu data away with that single, brief, and above all incorrect statement quoted above

The Fugu data is not the only evidence that most non-coding DNA is functionless. To start with the single celled amoeba has a genome 200 times larger than the human genome, most of it repetitive DNA. It would be hard to argue that the amoeba needs far more repetitive DNA than humans to organise its genome.

Furthermore, we have evidence from sequence conservation. If the repetitive DNA has a function, then its sequence should be conserved (for example if it serves as binding sites for regulatory proteins). However, the majority of the repetitive DNA is not conserved. Indeed, Kimura famously predicted that humans should have around about 1% protein coding genes based on mutation patterns (Kimura and Ohta, 1971). We actually have roughly 1-2% of our genome coding for protein (Nusbaum et al 2005). The sequence conservation data is compatible with over 90% of our genome doing not very much at all (either as regulatory sequences or protein coding sequences). Now, about 3-5% of repetitive DNA is conserved, which suggests that it might do something (Nobrega et al, 2004; Nusbaum et al 2005). So, what happens when this conserved repetitive DNA is removed?

The answer is “beggar all”. In a recent paper (Nobrega et al, 2004) megabase sections of non-coding DNA, including many conserved repetitive sequences, were deleted from the mouse genome. Nothing happened to the mice, they were perfectly normal. Of course something subtle might be wrong, but deleting a megabase of coding DNA gets you one dead organism, so this non-coding DNA can’t be as important as Shapiro and von Sternberg say. This data supports earlier experiments where smaller amounts of non-coding DNA were removed. Also, there are natural human mutants where large chunks of non-coding DNA containing conserved repetitive elements go AWOL with no effect (Sebat et al, 2004). Shapiro and von Sternberg don’t mention the Nobrega paper or this other evidence at all.

So, overall there is strong evidence that most of the non-coding DNA in complex metazoans is not functional (some might be purely structural scaffolding though). Around 3-5% of non-coding DNA is likely to be involved in regulation of gene activity, and some small percentage of non-coding repetitive elements may have some regulatory function, but even with the most generous estimates (which the Nobrega et al paper suggests are over estimates) at least 90% of the human (and other vertebrate) genome is doing nothing functionally important. Shapiro and von Sternberg don’t address these important findings, which says a lot for ID scholarship (or lack thereof).

- Kimura M and Ohta T (1971), Theoretic Aspects of Population Genetics, Princeton University Press, p28.

- Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. (2002) Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562.

- Nobrega MA, Zhu Y, Plajzer-Frick I, Afzal V, Rubin EM. (2004) Megabase deletions of gene deserts result in viable mice. Nature. 431(7011):988-93.

- Nusbaum C, et al., (2005) DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 18. Nature 437, 551-555

- Sebat, J. et al. (2004) Large-scale copy number polymorphism in the human genome. Science 305, 525–528