Stuck on you, biological Velcro and the evolution of adaptive immunity

I’ve been back from the Australian Health and Medical Research Congress, a 6 day research fest, for a couple of weeks now. However, my brain is still full with the heady delights of the work I experienced there. My students gave reasonably well received talks, and I have a whole grab bag of experiments to do now (or get my students to do). While there were many things that were of deep societal interest at the conference, one of the things that struck me most was a throwaway line in a lecture about cell adhesion. Nectin, a “molecular Velcro” that helps cells stick together is a member if the Ig superfamily.

To explain why it set a light bulb off in my head, and how the knowledge that molecular Velcro shares a structure with immunoglobulins throws deep insight into the evolution of the adaptive immune system, I will beg you patience and do a very brief review of the immune system first.

Animals have many defences against invading microorganisms, from simple passive barriers such as skin to the immune system. When we think of the immune system, we generally think of the adaptive immune system, and more specifically, antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that bind to specific molecules (usually protein or carbohydrates) on the surface of invading microorganisms. Antibodies can be secreted, like IgG, or membrane bound as well as secreted (like IgM). The antibody protein has a constant domain and a variable domain, with the variable domain binding to the microorganism. The adaptive immune system doesn’t come with a premade set of antibodies. When an organism invades, the section of the immunoglobulin gene that makes up the variable domain get shuffled around to make variable regions that bind with exquisite sensitivity to invading micro-organisms. Of course, this is highly simplified; see here for a more detailed explanation.

Explaining how the gene shuffling mechanism came about has been one of the triumphs of molecular immunology. A series of careful investigations and elegant experiments has shown that the rearranging part of the variable domain is due to horizontal transfer and incorporation of transib transposases into the immunoglobulin gene. You can read more about it here and here.

But now you can almost hear the ID folks sneering the in background “how very fortunate that there was a proto Ig molecule for the transposases to jump into, such a molecule would be functionless and could not evolve itself”. Not only could such a molecule have a function, it is part of a widespread family of proteins whose functions lend themselves to formation of the adaptive immune system.

In establishing that the adaptive immune system evolved, we need to show that there are plausible ancestors of the proteins involved in the adaptive immune system. One of the distinguishing features of immunoglobulins is a structural feature called the Ig fold, and if you read the literature on the immune system, you will learn that the immunoglobulins are part of the Ig fold superfamily, one of the largest families in the animal kingdom. But unless you are au fait with structural molecular biology, you will not know what the commonest role for these molecules is.

Basically, they are glue. The Ig superfamily is involved in cell-to cell adhesion and cell-surface adhesion. Sticking to things, or sticking to other cells, is a fundamental biological property that is found in the deepest cell lineages. In bacteria, the Ig superfamily proteins are cell surface proteins. In sponges, the Ig surface domain is fused to a common intracellular signalling domain, tyrosine kinase. This may surprise people, as most of us thing of glue as a passive thing, but the molecular glues are also active signalling molecules. In development, they help guide cells to their destinations, in phagocytes, the cellular scavengers that, amongst other things, engulf and consume bacteria; they help direct phagocytes to sites of infection.

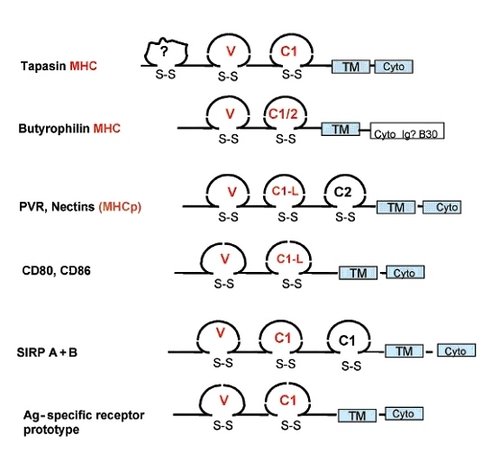

Proteins with an immunoglobulin structure, taken from Pancer et al., 2004. The molecular glue nectin is shown in the middle.

While immunoglobulins have an Ig fold, they also have a distinct Variable-Constant domain architecture. In the genome of the sea urchin, we see the first signs of this architecture in a number of proteins. In the sea squirt, an invertebrate chordate, the Variable –Constant architecture is clear in two classes of adhesion molecule, nectin and Junctional Adhesion Molecule (JAM). Jam is pretty interesting, as in vertebrates its relatives turn up on white blood cells involved in immunity, and play a role in phagocyte movement during inflammation. Phyolgenetically, nectin and JAM are the molecules that are closest to immunoglobulins.

Let’s take a brief recap here. Molecules which have the same overall structure as immunoglobulins are involved in cells sticking to things, especially phagocytes and other immune cells, cells which engulf bacteria. What would we expect of a proto-immunoglobulin? A protein on the white blood cell ancestors of lympocytes that sticks to things? Right now these adhesive proteins are looking good as proto-immunoglobulins. It would be better if you could demonstrate that something like nectin could bind bacteria or viruses. Well, yes, nectin and related proteins do bind viruses. The viruses actually use this adhesion to their advantage, to gain access to the cell, but adhesion molecules can bind immunologicaly important microorganisms, which is an important proof of concept.

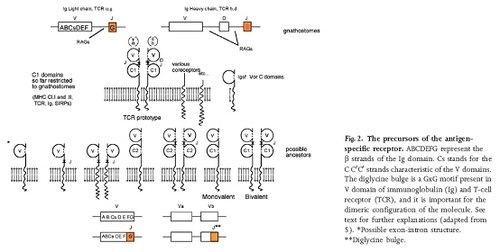

But wait, there is more! When Behe (and most of the ID community) write on the immune system, they ignore the innate immune system. The innate immune system is very old, much older than the adaptive immune system. It is present in some form in all metazoans investigated to date. It includes amongst its repertoire secreted proteins that immobilise bacteria in a sticky mass, and a series of non-rearranging receptors for bits of bacterial cell surface. In molluscs, one of the anti-parasite molecules is FREP, which has an Ig non-rearranging V domain at the business end. In the invertebrate cephalochordate Amphioxus, there is a family of very immunoglobulin like-molecules, Variable domain Chitin Binding Proteins, which are involved in innate immunity. In lampreys and hagfish, jawless vertebrates, there are Ig fold proteins that are almost the spitting image of modern rearranging immunoglobulins that are found in the equivalent of lymphocytes and are involved in innate immunity.

Precursors of an antigen specific receptor, taken from Pancer et al., 2004

So we have evidence for a pathway from simple adhesive molecules, to signalling adhesive molecules, to signalling adhesive molecules which help defence cells, to innate immune receptors. Behe (and other ID apologists) likes to give the impression that the all elements of the adaptive immune system had to evolve simultaneously, in one burst[**]. But as we have seen, by the time the transib transposases inserted themselves into the proto-immunoglobulin gene, these molecules had hundreds of millions of years adaptation to an immune function already.

And it all started with molecular glue.

* Such as the panel on Stem Cell research, which was conducted shortly before the parliamentary vote that removed restrictions on therapeutic cloning.

** One frustrating thing is that Behe will always discuss the most complicated mammalian example, and ignore simpler systems in the same organism, or in ancestral organisms. For example, Behe presents the B-cell/T-cell interaction as if this is the only way B-cells are activated (Pgs 123-124, Darwin’s Black Box). But B-cells can be activated without T-cells, and in fish and amphibians, B-cells are also phagocytes, providing a link between the adaptive and innate immune systems. Similarly in the complement and clotting systems, Behe ignores simpler systems in simpler organisms.

- Ono E, Tomioka Y, Watanabe Y, Amagai K, Taharaguchi S, Glenisson J, Cherel P. The first immunoglobulin-like domain of porcine nectin-1 is sufficient to confer resistance to pseudorabies virus infection in transgenic mice. Arch Virol. 2006 Sep;151(9):1827-39.

- Kubrycht J, Sigler K, Ruzicka M, Soucek P, Borecky J, Jezek P. Ancient Phylogenetic Beginnings of Immunoglobulin Hypermutation. J Mol Evol. 2006 Oct 6; [Epub ahead of print]

- Muller CI, Blumbach B, Krasko A, Schroder HC. Receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatases: origin of domains (catalytic domain, Ig-related domain, fibronectin type III module) based on the sequence of the sponge Geodia cydonium. Gene. 2001 Jan 10;262(1-2):221-30.

- Du Pasquier L, Zucchetti I, De Santis R. Immunoglobulin superfamily receptors in protochordates: before RAG time. Immunol Rev. 2004 Apr;198:233-48.

- Haruta C, Suzuki T, Kasahara M. Variable domains in hagfish: NICIR is a polymorphic multigene family expressed preferentially in leukocytes and is related to lamprey TCR-like. Immunogenetics. 2006 Apr;58(2-3):216-25. Epub 2006 Mar 16.

- Corada M, Chimenti S, Cera MR, et al., Junctional adhesion molecule-A-deficient polymorphonuclear cells show reduced diapedesis in peritonitis and heart ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Jul 26;102(30):10634-9

- Pancer Z, Mayer WE, Klein J, Cooper MD. Prototypic T cell receptor and CD4-like coreceptor are expressed by lymphocytes in the agnathan sea lamprey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Sep 7;101(36):13273-8. Epub 2004 Aug 24.