Update on PNAS flagellum paper

Those who have been following the comments section of the first post on the PNAS flagellum paper, entitled “Stepwise formation of the bacterial flagellar system,” will see that there have been several developments: ScienceNOW at Science magazine has uncritically reported the PNAS paper’s all-flagellar-genes-came-from-one conclusion; Behe and other IDers are getting into the act, although they are so clueless they don’t really even understand why the PNAS paper is problematic; and PZ Myers and I have dropped hints that several of us PT bloggers are reaching the conclusion that this paper is looking worse, not better, after close examination. We will have more on the technical methodology issues in the next few days. For the moment I would just like to offer a simple response to some comments, and a simple but powerful reason that the “all core flagellum genes are descended from one ancestral gene” does not work.

First, the comments. Some commentators have reacted along the following lines: (1) maybe the paper isn’t so bad, just speculative; and/or (2) maybe I’ve misread the paper or its conclusion was poorly worded, and maybe the authors just meant to argue that some of the 24 core flagellar proteins were related, not all 24 proteins.

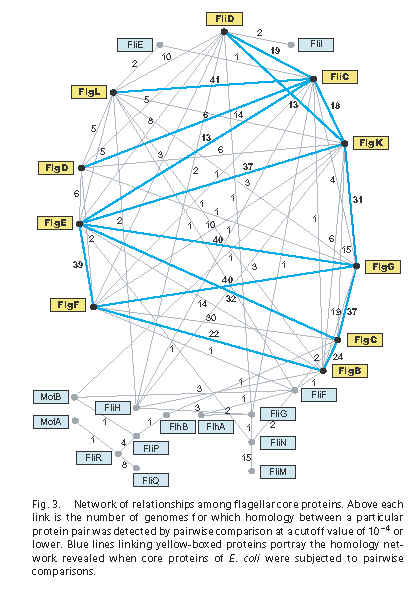

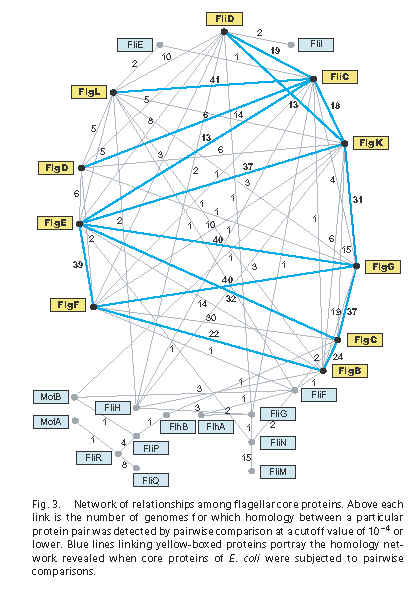

Unfortunately – and I mean unfortunately because I wish one of these options was true – neither idea is a supportable interpretation of the authors’ views. Have another look at Figure 3 from the Liu & Ochman paper:

- The boxes contain the names of all 24 core flagellar proteins that the authors identified.

- Each line represents a significant homology hit using pairwise BLAST. The claimed e-value cutoff for significance is 10-4 (e=0.0001), which is pretty conservative – researchers sometimes assign homology pretty confidently on e-values up to 10-2 (e=0.01).

- The numbers represent the number of times, in 41 tested bacterial genomes, that the homology was found. For example, the already well-known homology between FliC (flagellin) and FlgL (flagellin/hook adapter) was recovered 41/41 times.

- The blue lines represent homologies retrieved in E. coli K12, the grey lines hits retrieve in any of the 41 genomes.

In some ways, Figure 3 confirms conventional wisdom. The axial filament of the flagellum – the tube that extends from the basal body out to the filament – is made up of a series of proteins, approximately in this arrangement, with these copy numbers:

~9 copies of FliE (FliF-rod linker) ~6 copies of FlgB (inner rod) ~6 copies of FlgC (middle rod) ~6 copies of FlgF (middle rod) ~26 copies of FlgG (outer rod) ~130 copies of FlgE (hook – the curvy part in most flagellum diagrams) ~11 copies of FlgK (first hook-filament linker) ~11 copies of FlgL (second hook-filament linker) ~20,000 copies of FliC (flagellin, makes up the flagellar filament)

The long tube that these proteins form is called the “axial filament” and the proteins as a group are “axial proteins.”

Now, if you remember Table 1 from Pallen and Matzke 2006, a simple protein BLAST search will return two groups of relatives within the axial proteins:

- FlgBCFGEK, the rod+hook+first linker protein, is one related group

- FlgL (the 2nd linker) + FliC (flagellin) is the second related group

Figure 3 supports these already-known relationships, which are all supported by 24 or more hits, usually 30 or more hits.

However, the point of Liu & Ochman’s Figure 3is that not just the axial proteins, but all 24 proteins are connected by one or more homologies to other proteins. Just to make sure the authors really mean this, let’s examine relevant bits of the paper.

It is kind of strange to read through the Liu and Ochman paper – you can almost watch their thesis mutate from an interesting, if unoriginal, observation about axial proteins, to a sweeping, wildly unsupportable conclusion about all core flagellar proteins:

[Abstract] These results show that core components of the bacterial flagellum originated through the successive duplication and modification of a few, or perhaps even a single, precursor gene.

OK, here, maybe they just mean *some* of the core flagellar components came from a single common ancestor.

[End of the introduction] Our results show that flagellum [should be “the flagellum”, sic] originated very early, before the diversification of contemporary bacterial phyla, and evolved in a stepwise fashion through a series of gene duplication, loss and transfer events.

This is not wildly wrong as stated, although the phylogenetic conclusion about flagella being in the last common ancestor of bacteria is disputed, e.g. by Cavalier-Smith. Moving on:

Core Flagellar Proteins Arose Through the Duplication and Diversification of a Single Precursor.

That is pretty clear right there in the section heading: “Single Precursor.”

Core Flagellar Proteins Arose Through the Duplication and Diversification of a Single Precursor. When each of the 24 core flagellar proteins of E. coli are compared (via BLAST) to all proteins encoded in the E. coli genome, their best and often only hits are to other core flagellar proteins. This pattern indicates that the structural genes specifying the portion of flagellum residing outside of cytoplasmic membrane (i.e., the rod, hook, and filament) are paralogs and were derived from one another through duplications.

Here they are just talking about the E. coli K12 genome. We have already discussed the axial proteins, so you know this part is confirming conventional wisdom (connecting the FliC+FlgL group to the FlgBCFGEK group is a controversial addition, but that problem is small potatoes at the moment).

Let’s look at Figure 3 again.

The E. coli hits are the blue lines, and the matched E. coli proteins are the yellow boxes. I count 14 15 blue lines linking 10 yellow boxes, all axial proteins.

The paper continues on, to look for homologies outside of the flagellum, inside the E. coli K12 genome:

Aside from these matches to other core proteins, pairwise comparisons of these flagellar proteins to the >4,000 nonflagellar proteins encoded by the entire E. coli genome recovered cumulatively a total of only 24 hits that reached the same level of significance. […]

We will skip over some details which are vague and problematic for other reasons, but which are, again, small potatoes. The conclusion of their search of E. coli:

Thus, we conclude that despite their antiquity, the similarities among core proteins to one another are more common and, on average, stronger than to nonflagellar proteins.

It is none too clear, but I think what they are trying to say here is that with the E. coli K-12 genome, they got:

(a) 14 15 homologies found between 10 flagellar proteins (out of 24 total flagellar proteins)

(b) and 24 homologies found between ?? flagellar proteins (they don’t say how many) and 4,000 nonflagellar proteins

Because (a) is a higher proportion than (b), the authors say that “on average” the within-flagellum homologies are more common. OK I guess. This doesn’t establish anything about all the flagellar proteins evolving via internal duplications – if you’ve got external homologies then you have evidence that flagellar proteins could have once had an nonflagellar ancestors.

What about the other 40 genomes? The authors continue:

We repeated this analysis and compared the core gene set of each other flagellated bacterium to all proteins encoded in the corresponding genomes and among themselves, and we obtained a similar result, i.e., the best (and often the only) hits of the flagellar core genes were to other flagellar core genes.

This is just more of the axial protein homology detection.

However, by extending this analysis beyond E. coli, the similarity-relationships and links among several other core genes were resolved. For example, a highly significant match between fliM and fliN (that was not detected for E. coli homologs) was evident in 15 genomes from diverse bacterial subdivisions (Fig. 3).

The FliM-FliN homology has been well-known for quite a while. Apparently they don’t catch the well-known homology between the chemotaxis protein CheC and FliM because they don’t do a general BLAST search of a full database. (FliM has two main domains, homologous to CheC and FliN respectively.)

Cumulatively, each of the 24 core genes shows significant similarly to one or more of the other core genes (Fig. 3), a pattern that would result from their successive origination from one another by independent gene duplications and/or gene fusions.

See, I wasn’t making it up. They really are basing their all-from-one-gene conclusion on Figure 3.

Comparisons of the complete genome sequences of flagellated bacteria revealed that the flagellum is based on an ancestral set of 24 core genes for which homologs are present in genomes of all bacterial phyla. The most striking finding from our analysis is that these core genes originated from one another through a series of duplications, an inference based on the fact that they still retain significant sequence homology.

”[T]hese core genes originated from one another” – pretty clear what they meant.

Although sequence similarities among some of the rod and hook proteins were noted in early analyses (24), the degree of paralogy for the ancestral set of flagellar genes, and its implications for the origins of the bacterial flagellum, have gone unrecognized.

Um, right. That’s because the paralogy has not been detected by anyone else, except for the axial proteins and FliN-FliM. Figure 3 reports about 50 new homology matches (the grey lines plus a few blue lines) for 14 15 flagellar proteins. Authors and reviewers might have pondered profitably the question of why no one else was able to BLAST up this cornucopia of results before.

[Summary]

To ascertain the ancestry of the flagellar core genes, we searched initially for homologs of each gene within the E. coli genome, which has the highest proportion of functionally annotated genes. The resulting network, involving only 10 of the 24 core genes, provided a very conservative view of the relationships and paralogy among the core genes but showed that flagellar genes were derived largely from other flagellar genes with apparently little input from other coding sequences.

All this means is that within a single E. coli genome (K-12) they didn’t find much beyond the axial protein homologies.

Extending these analyses to include other genomes uncovered additional links among flagellar proteins and revealed that the entire set of core genes could be formed through the duplication and divergence of previously existing flagellar genes.

Figure 3 again. Yep, I guess they really do think this. “Entire set” is not ambiguous.

That the analysis of the E. coli did not resolve all of the links among core genes is not surprising given that these genes are ancient and have followed independent histories within bacterial lineages. It was originally hypothesized that biological pathways and structures might expand through the successive addition and modification of their preceding components (27). Although there is diminishing evidence that the recruitment of new enzymes into metabolic pathways occurs by this process (28), it is apparently the manner by which the bacterial flagellum arose.

In other words, the all-internal-duplications model has failed for metabolic pathways, and the cooption-from-diverse-sources model is now dominant – but we’ll resurrect the old discredited model for the flagellum!

[end of the conclusion paragraph]

As with the evolution of other complex structures and processes (29–32), we have shown the bacterial flagellum too originated from “so simple a beginning,” in this case, a single gene that underwent successive duplications and subsequent diversification during the early evolution of Bacteria.

This conclusion sentence is the 5th or 6th time the authors explicitly endorse the “all flagellar genes came from one” model. So let’s not have any more questions about what the authors meant to say.

Now, why am I skeptical? I posted some scattershot reasons on Monday. Some us PT posters are chewing on more technical issues. But to really get a visceral sense of the problem of claiming that all the flagellar genes are homologous, you just have to look at some structures. Here is FliI, the ATPase that powers the secretion of axial proteins like FliC:

(from Imada et al. 2007, PNAS)

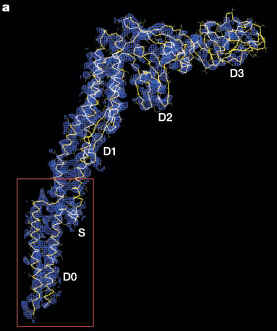

Here is FliC, aka flagellin, which is supposed to be just two homology links away from FliI in the Liu/Ochman Figure 3:

(from Yonekura et al. 2003, Nature)

You can also compare the two proteins when assembled into multimers. FliI assembles into a homohexamer:

(from Imada et al. 2007, PNAS)

FliC assembles into the flagellar filament:

(from here)

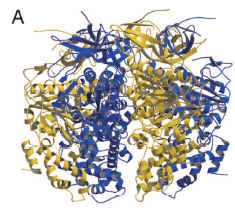

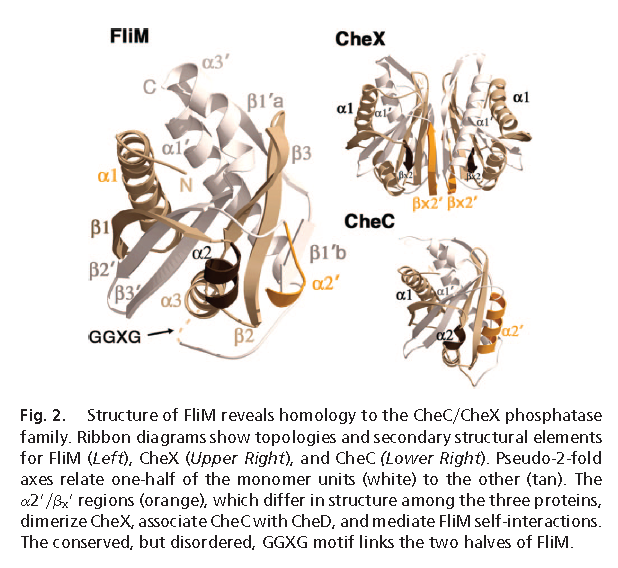

For comparison, this is what two protein structures look like when they are homologous. These are the homologous domains in CheC (a chemotaxis protein in some flagella), and FliM (part of the flagellum base, which interacts with chemotaxis proteins to produce the switching in rotation direction). (FliM is basically two main domains, homologous to CheC + FliN. Liu & Ochman caught the FliN homology but apparently not the CheC one.)

(from Park et al. 2006, in PNAS)

(from Park et al. 2006, in PNAS)

You might have noticed that FliC and FliI do not exactly exhibit the kind of structural similarity shown by the homologous FliM and CheC.

I conclude that FliC and FliI are not homologous. Therefore not all core flagellar proteins are homologous. Therefore they didn’t come from a single ancestral ur-flagellar gene. Therefore the conclusion of Liu & Ochman is wrong. Case closed.