On the evolution of Irreducible Complexity

There has been a spate of interest in the blogosphere recently in the matter of protein evolution, and in particular the proposition that new protein function can evolve. Nick Matzke summarized a review (reference 1) on the subject here. Briefly, the various mechanisms discussed in the review include exon shuffling, gene duplication, retroposition, recruitment of mobile element sequences, lateral gene transfer, gene fusion, and de novo origination. Of all of these, the mechanism that received the least attention was the last – the de novo appearance of new protein-coding genes basically “from scratch”. A few examples are mentioned (such as antifreeze proteins, or AFGPs), and long-time followers of ev/cre discussions will recognize the players. However, what I would argue is the most impressive of such examples is not mentioned by Long et al. (1). Below the fold, I will describe an example of de novo appearance of a new protein-coding gene that should open one’s eyes as to the reach of evolutionary processes. To get readers to actually read below the fold, I’ll summarize – what we will learn of is a protein that is not merely a “simple” binding protein, or one with some novel physicochemical properties (like the AFGPs), but rather a gated ion channel. Specifically, a multimeric complex that: 1. permits passage of ions through membranes; 2. and binds a “trigger” that causes the gate to open (from what is otherwise a “closed” state). Recalling that Behe, in Darwin’s Black Box, explicitly calls gated ion channels IC systems, what the following amounts to is an example of the de novo appearance of a multifunctional, IC system.

An IC System From Scratch

The subject of this essay is a fascinating protein that I will call T-urf13 (see the first footnote). This protein, and its gene, was discovered in the mitochondrial genome of certain maize varieties that had been bred to be male-sterile (see footnote 2). There are many different cytoplasmic male sterility (or cms) “traits” in maize, and T-urf13 is found only in so-called cmsT maize (T stands for Texas). This protein was discovered, and studied, owing to an unfortunate circumstance in the 1969 and 1970 (see reference 2 for a review). Briefly, cmsT maize fields were devastated by the appearance of a fungal pathogen (Cochliobolus heterostrophus race T) that seemingly had a unique “taste” for cmsT plants. (The disease is known as Southern corn leaf blight.) After many years of genetic, molecular, and ultimately biochemical studies, it was found that disease was due to a unique susceptibility of cmsT maize to a toxin produced by the fungus (see reference 3 for a recent reviewon the biosynthesis of this toxin). It was also found that disease susceptibility, as well as male sterility, were due to rearrangements of the maize mitochondrial genome, resulting in a novel cmsT-specific locus (see the following paragraph; 4). Finally, it was found that this novel locus encoded a small protein, T-urf13, whose production correlated exactly with both male sterility and disease susceptibility (5).

(I apologize if the pathogen’s name is not familiar or current – I long ago gave up trying to keep pace with the taxonomy of fungi.)

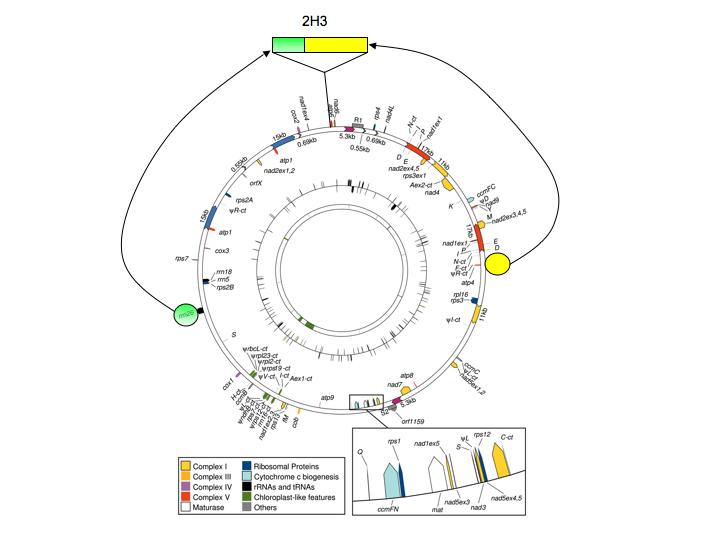

The origins of the cmsT locus are fascinating. Several years ago, this locus was cloned and sequenced, and the sequence compared with normal maize mitochondrial DNA. This analysis revealed that the T-urf13 locus was the product of numerous recombination events (as many as seven different ones; along with reference 4, reference 6 has a nice overview of this). The consequence of these recombination events was the cobbling together of a number of disparate mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) segments (I have tried to illustrate their origins in Figure 1) to yield a novel DNA segment in the cmsT mitochondrial genome.

Figure 1. I have superimposed two sections (colored circles) that have been brought together to form the unique region (2H3) in the mitochondrial genome of cmsT maize. For this, I have used the circular map of the maize NB mitochondrial genome (downloaded from Clifton, S. W., et al. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3486-3503) to show the relative positions of the two major parts of the 2H3 region, as well as the location in the genome of the 2H3 region itself. Note that these circles, as well as the 2H3 region, are not drawn to scale. Also note that the NB genome map is being used for convenience (the paper has a nice figure that allows me to make the basic point). The actual genome from which cmsT was derived may differ in some ways from the NB genome, although not in the general features shown here. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the T-urf13 gene lies within the green shaded portion of 2H3.

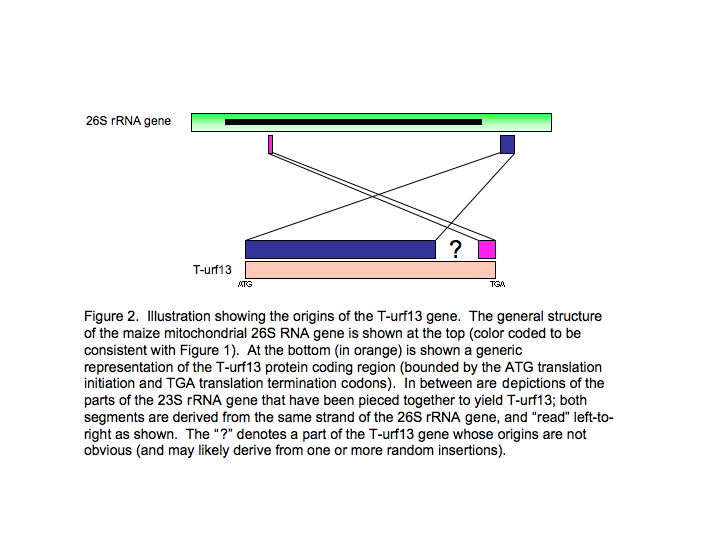

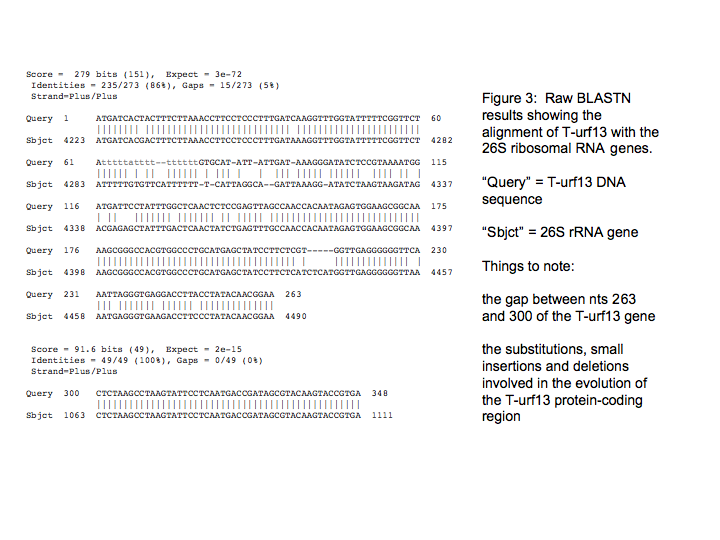

One consequence of these rearrangements was the protein-coding region for T-urf13. What is remarkable is that none of the T-urf13 protein coding region came from other protein-coding genes. This is illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. Briefly, this novel protein-coding” gene consists of a segment of the 3’-flanking region of the mitochondrial 26S ribosomal RNA gene, a much smaller (and not contiguous) part of the RNA-coding part of the same gene, and a number of bp that seemingly appeared from out of the blue (Figure 2).

Closer perusal of the sequences (Figure 3) reveals that the origination of this gene involved, not just the piecing together of two different parts of the mitochondrial genome, but several other mutational events (point mutations, small insertions and/or deletions).

The bottom line is that T-urf13 is a new protein, encoded by a gene that has no protein-coding antecedents; it is, bluntly, a new protein that arose “from scratch”, through a series of duplications, recombinations, and other mutations that occurred spontaneously in the course of the breeding process that gave rise to the cmsT line.

These points are already problematic for the assertion by ID proponents that new protein-coding information cannot arise by natural processes. But T-urf13 is more than a nondescript polypeptide that happens to affect male fertility in corn. It turns out that T-urf13 is a membrane protein, and in membranes it forms oligomeric structures (I am not sure if the stoichiometries have been firmly established, but that it is oligomeric is not in question). This is the first biochemical trait I would ask readers to file away – this protein is capable of protein-protein interactions, between like subunits. This means that the T-urf13 polypeptide must possess interfaces that mediate protein-protein interactions. (Readers may recall Behe and Snokes, who argued that such interfaces are very unlikely to occur by chance.)

T-urf13 also binds to the toxin produced by the fungal pathogen. But it does not just bind the toxin “passively” – upon binding, a non-selective ion channel is opened, leading to dissipation of transmembrane ion gradients, and all of the resulting events that accompany collapse of proton-motive force. (In mitochondria, this will lead to uncoupling and crippling of mitochondrial function; this is probably why cmsT plants are so devastated by the disease.) This is the second biochemical trait that readers should keep fresh in their minds – T-urf13 is a gated ion channel. (This an the other interesting biochemical properties of Turf13 are reviewed in reference 7.)

Those who have read Darwin’s Black Box might recall Behe’s description of a gated ion channel. On pp. 108-110, Behe describes the signal recognition particle (SRP)-mediated transport of proteins (footnote 3) as a gated transport process. In so doing, he asserts (among other things) that “(b)ecause gated transport requires a minimum of three separate components to function, it is irreducibly complex”. The three components he describes for SRP-mediated protein translocation are the signal peptide, SRP, and the transport channel. The T-urf13 gated ion channel also consists of three components – the fungal toxin (footnote 4) is analogous to the signal peptide, the toxin binding site is analogous to SRP, and the ion channel is analogous to the protein channel. In case this comparison has hidden the bottom line, it is this – T-urf13 is irreducibly complex in exactly the same way that Behe asserts for SRP-mediated protein transport.

The take-home message of all this is: portions of the maize mitochondrial genome that do not normally encode any protein were shuffled, extensively, so as to cobble together an expressed gene that encodes, not just any old polypeptide, but a multimeric gated ion channel. In other words, an irreducibly complex structure arose in one fell swoop, using DNA sequences that do not encode proteins. Basically, this is a case of IC from scratch.

What does all this mean? A linchpin of ID thought is the notion that functional proteins, especially multifunctional ones, cannot arise de novo via natural processes. This proposition is one of Paul Nelson’s antievolutionary arguments that center on ORFans (briefly, the appearance of new function is one of Nelson’s alleged discontinuities), it is a part of the reason so many ID supporters retreat to the stage of the OOL when faced with other facts (presumably, they think that the origins of the first functioning proteins are beyond the grasp of natural mechanisms), it is ultimately where Behe’s ideas about irreducible complexity end up. The example discussed in this essay shows that even complex multifunctional proteins are well within the “reach” of normal, natural molecular processes.

Footnotes.

-

Veterans of the ARN boards will recognize this subject. One of the two threads that discussed T-urf13 has apparently been lost, but the other can still be accessed.

-

Male sterility is a trait used by plant breeders to promote outcrossing; in crops like maize, it is used in the production of hybrids, which increases yield through the phenomenon known as hybrid vigor. The trait is called “cytoplasmic male sterility” because it is inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion. Briefly, cms is maternally inherited, so that 100% of the progeny of a cross in which the mother is male sterile will also be cms. In animals, maternal inheritance is a hallmark of a mitochondrial gene; the same holds in plants, but maternal inheritance also applies for chloroplast genes.

-

SRP-mediated transport is the process by which proteins destined for vesicular transport and export out of the cell are synthesized. Briefly, proteins destined for transport possess N-terminal signal peptides that are recognized by the ribonucleoprotein Signal Recognition Particle; association of the SRP-nascent polypeptide peptide with the translating ribosome causes a pausing, which is released upon “docking” with the transport apparatus on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum.

-

The toxin made by C. heterostrophus race T is a polyketide. It is beyond the scope of this essay to detail this class of compound, or the fascinating enzymes that synthesize them. Suffice to say that these enzymes add another layer of “complexity” to this subject, in that a rather complex set of activities had to evolve, along with the maize mitochondrial genome, to “assemble” the IC T-urf13 system.

References

-

Long M, Betran B, Thornton K, Wang W. 2003. The origin of new genes: Glimpses from the young and old. Nature Rev Genet. 4: 865-875. (a review, cited by Nick Matzke, on the origins of genes)

-

Levings CS 3rd. 1990. The Texas cytoplasm of maize: Cytoplasmic male sterility and disease susceptibility. Science 250, 942-947. (a nice summary of the phenomenon)

-

Turgeon BG, Baker SE. 2007. Genetic and genomic dissection of the Cochliobolus heterostrophus Tox1 locus controlling biosynthesis of the polyketide virulence factor T-toxin Adv Genet 57, 219-261. (a recent review of the synthesis of the T toxin)

-

Dewey RE, Levings CS 3rd, Timothy DH. 1986. Novel recombinations in the maize mitochondrial genome produce a unique transcriptional unit in the Texas male-sterile cytoplasm. Cell 44(3):439-49. (characterization of the T-urf13 locus in cmsT maize)

-

Dewey RE, Timothy DH, Levings CS 3rd. 1987. A mitochondrial protein associated with cytoplasmic male sterility in the T cytoplasm of maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84(15):5374-5378. (links the T-urf13 protein with cms)

-

Hanson MR. 1991. Plant mitochondrial mutations and male sterility. Annu Rev Genet. 25:461-86. (A review that discusses cms in a broad context)

-

Rhoads DM, Levings CS 3rd, Siedow JN. 1995. URF13, a ligand-gated, pore-forming receptor for T-toxin in the inner membrane of cms-T mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 27(4):437-45. (a review of the biochemical properties of T=urf13)