A complete Neandertal mtDNA genome

In 1997 the first successful extraction of Neandertal DNA was announced to great fanfare (Krings et al. 1997). This DNA was not from the nuclear DNA (from cell nuclei) which determines most of our physical characteristics, but mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the small energy-producing organelles which are inside all of our cells 1. It so happens that mtDNA is easier to extract from ancient bones than is nuclear DNA. Krings et al reconstructed a 379 base sequence from the Neandertal mtDNA, out of the full mtDNA length of more than 16,000 bases. Since then, many other researchers have also extracted mtDNA sequences from Neandertal bones (and one team has even recovered some nuclear DNA).

Now, for the first time, a complete mtDNA sequence has been recovered, from a 38,000 year old Neandertal fossil from the Vindija cave in Croatia. The results were published in August 2008 in the journal Cell: A Complete Neandertal Mitochondrial Genome Sequence Determined by High-Throughput Sequencing (Green et al. 2008).

Here is one of the most important conclusions from the paper’s summary:

Green et al. 2008 wrote:

Analysis of the assembled sequence unequivocally establishes that the Neandertal mtDNA falls outside the variation of extant human mtDNAs, and allows an estimate of the divergence date between the two mtDNA lineages of 660,000 ± 140,000 years.

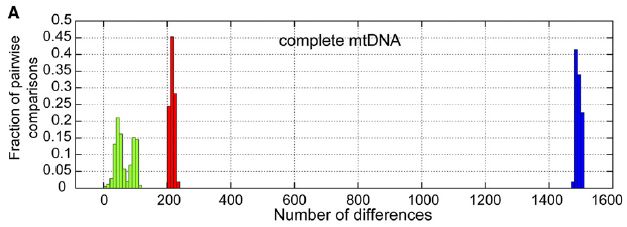

The Neandertal mtDNA sequence was compared with mtDNA from chimpanzees and 53 modern humans. The human mtDNA sequences had between 2 and 118 differences from each other. The number of differences between the human mtDNAs and the Neandertal mtDNA varied from 201 to 234. This graph shows the differences between the human, Neandertal and chimp groups, and the human group:

X axis, the number of sequence differences

Y axis, the fraction of pairwise comparisons. (Green et al. 2008)

This is not unexpected; it confirms the conclusion from the earlier Krings et al. 1997 paper (you can see the equivalent graph from that paper here). In that paper, the 994 human sequences had between 1 and 24 differences from each other (over a partial mtDNA sequence). The number of differences between the human sequences and the Neandertal sequence varied from 22 to 36. Because the minimum distance between any human and the Neandertal (22) was slightly less than the maximum distance between any two modern humans (24), some creationists (e.g. Lubenow 1998) misinterpreted these figures to claim that the 1997 Neandertal mtDNA was within the modern human range. (It was a misinterpretation because it was comparing apples (a minimum distance between N’tals and any human) with oranges (a maximum distance between any two humans)). As an alternative explanation of the data, Lubenow suggested that maybe early humans formed a large population which had far greater genetic variability, most of which had since been lost. This was, at the time, a conceivable conjecture, though not one I would have wanted to bet on. But further study has disproved it; all the subsequent Neandertal mtDNA sequences which have been recovered have been similar to each other, and dissimilar to modern humans.

Now that we have a complete Neandertal mtDNA genome, the distinction between the Neandertal and modern human mtDNA is even more striking. It strengthens the view that Neandertals should be designated a separate species Homo neanderthalensis, because even if they could interbreed with the ancestors of modern humans (and they probably could, and possibly did on occasion 3) there does not seem to have been a significant amount of genetic interflow happening between the two populations. We don’t find Neandertal mtDNA in modern humans, and vice versa. Humans and Neandertals seem to have split off around 600,000 years ago and developed separately thereafter.

For a more in-depth analysis of this paper, see John Hawks’ blog entry Complete Neandertal mitochondrial sequence, and selection on human (not Neandertal) mtDNA.

Footnotes

1. mtDNA also has the intruiging property that it is always (or almost always; there is some dispute over this) inherited only from the mother, and not the father. This means that it is useful for determining relationships through maternal lines.

2. The graph shows the Neandertal group between the human and chimp groups. This does not mean that Neandertals are intermediate between humans and chimps. In fact, both are about equally distant from chimps (which is what we would expect from evolutionary theory). The Neandertal group is in the middle because the graph compares each group with modern humans. If instead it had compared each group with the Neandertal mtDNA, then the human group would have been between the Neandertals and the chimps.

3. Just because two individuals can breed does not mean they belong to the same species. Although there are many competing concepts as to what constitutes a ‘species’, usually it is considered to be a population of individuals that successfully interbreed in the wild. Populations that could interbreed in theory but don’t in practice are therefore different species.

References

Krings M., Stone A., Schmitz R.W., Krainitzki H., Stoneking M., and Pääbo S. (1997): Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell, 90:19-30.

Green R., Malaspinas A-S, Krause J., Briggs A., et al. (2008) A Complete Neandertal Mitochondrial Genome Sequence Determined by High-Throughput Sequencing. Cell, 134:416-426.

Lubenow M. (1998), Recovery of Neandertal mtDNA: an evaluation. Technical Journal, 12(1):87-97