Dean Kenyon: a young-earth creation scientist who was later relabeled an intelligent design proponent

Over on the Thinking Christian blog I have been challenged on my assertion in several publications (e.g. in this PNAS article) that “intelligent design” leader Dean Kenyon – a coauthor of Of Pandas and People and a Discovery Institute fellow – is actually a young-earth creationist and “creation scientist.” Usually I get these things right, but I was recently wrong about Cornelius Hunter, and only some of the evidence is on the Dean Kenyon entry on Wikipedia, so it is worth it to review the evidence.

Over on the Thinking Christian blog I have been challenged on my assertion in several publications (e.g. in this PNAS article) that “intelligent design” leader Dean Kenyon – a coauthor of Of Pandas and People and a Discovery Institute fellow – is actually a young-earth creationist and “creation scientist.” Usually I get these things right, but I was recently wrong about Cornelius Hunter, and only some of the evidence is on the Dean Kenyon entry on Wikipedia, so it is worth it to review the evidence.

There are many lines of evidence for the proposition that Kenyon is/was a young-earther. It is true that he wasn’t always like this – in the late 1960s he was a young origin-of-life researcher, and he coauthored the book Biochemical Predestination which accepted the standard view on evolution and the age of the Earth. But in the late 1970s he changed his mind:

“Then in 1976, a student gave me a book by A.E. Wilder-Smith, The Creation of Life: A Cybernetic Approach to Evolution. Many pages of that book deal with arguments against Biochemical Predestination, and I found myself hard-pressed to come up with a counter-rebuttal. Eventually, several other books and articles by neo-creationists came to my attention. I read some of Henry Morris’ books, in particular, The Genesis Flood. I’m not a geologist, and I don’t agree with everything in that book, but what stood out was that here was a scientific statement giving a very different view of earth history. Though the book doesn’t deal with the subject of the origin of life per se, it had the effect of suggesting that it is possible to have a rational alternative explanation of the past.”

Kenyon, Dean, and Pearcey, Nancy (1989). “Up From Materialism: An Interview with Dean Kenyon.” Bible-Science Newsletter, 27(9), 6-9. September 1989.

(Note: both A.E. Wilder-Smith and Henry Morris are famous young-earther creation scientists. Nancy Pearcey is a young-earther too – she once wrote that humans were contemporaneous with dinosaurs. And the Bible-Science Newsletter was a famously rabid young-earth publication that sometimes even flirted with geocentrism.)

It’s not quite clear how this revolution happened – I suspect there was more to it than what happened in 1976. For example, in the early 1970s Kenyon published some weird stuff for an OOL researcher, for example several short review articles on acupuncture, on the idea that viruses may originate de novo when environmental pollution stresses the body (see also the 1972 newspaper article I found on the article by Adolphe Smith and Dean Kenyon, quoted below), and on the idea that new life was originating through self-organization in the present day. This stuff is not necessarily crazy (however, I have the articles, and they seem to be quite a ways from vaguely similar modern ideas – e.g. it looks like he is not talking about the idea that genome-encoded viruses could re-activate). However, it is a long ways from the technical chemistry and experimental work on which he did his Ph.D. in the 1960s, and which petered out in the 1970s.

In 1974 Kenyon spent his sabattical at Trinity College in Oxford on science/religion issues:

Then, during the 1970s, I began to rethink my Christian faith. I had been raised as a Christian, but I now began to take a fresh look at my beliefs and they began to have a greater personal significance. In 1974, I went to Oxford University as part of a sabbatical leave and spent the time reading and interviewing people on the relation between science and Christian faith. At that time, most of the people I talked to were theistic evolutionists. I went through a period for a couple of years of being quite intrigued with the works of Teilhard de Chardin. His writings were very popular in Oxford at the time.

Kenyon, Dean, and Pearcey, Nancy (1989). “Up From Materialism: An Interview with Dean Kenyon.” Bible-Science Newsletter, 27(9), 6-9. September 1989.

(note: this paragraph comes just before the previous paragraph I quoted)

Before that, “Kenyon spent the 1969-1970 academic year on a fellowship at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, where he reviewed the contemporary literature on the relationship of science and religion. As an Episcopalian, he was not inclined to see any conflict between God and Darwinism. Yet this was for him a season of intellectual doubt. [goes on to discuss the Wilder-Smith book]” (Witham 2002, p. 163).

And finally, the early 1970s were not exactly a placid time in the U.S., especially on college campuses, and very especially at San Francisco State. There is no specific evidence for this having an effect on Dean Kenyon, but it wouldn’t be surprising if the general chaos of the times had an influence.

Anyway, to summarize some of the evidence for Dean Kenyon being a young-earther:

* Kenyon was scheduled to testify in defense of the “creation science” laws in the McLean and Edwards cases.

* In 1982, Kenyon wrote the forward to Henry Morris’s YEC book What is Creation Science?

* Through the 1980s, there was a variety of “creation science” literature which cited Kenyon as an example of an evolutionist who saw the light and adopted creation science.

* Of Pandas and People was derived from an explicitly “creation science” text, and even the published version explicitly depicted the young-earth view as reasonable, along with the old-earth view. (see also: Matzke 2009, “But Isn’t It Creationism?”, in But Is It Science?, edited by Pennock and Ruse)

* Kenyon is a speaker, writer, and board member for the Kolbe Center, a Catholic fringe group which, unlike most modern Catholics, lobbies for the young-earth view.

* In fairly recent history, Kenyon has attended/presented at some of the International Conferences on Creationism, a well-known YEC series of conferences.

* And apparently just last year, Kenyon endorsed this explicitly YEC book:

Kolbe Center for the Study of Creation 952 Kelly Rd., Mt. Jackson, VA 22842 Tel: 540-856-8453 E-Mail: howen@shentel.net

For me You have created the skies scattered with stars . . . and all the beautiful things on earth

(St. Maximilian Kolbe) http://www.kolbecenter.org

Dear Friends of the Kolbe Center,

Pax Christi!

As Christmas rapidly approaches, I am happy to announce a new breakthrough for our apostolate. Fr. Victor Warkulwiz, our chief theological advisor, has written a major work on the doctrines of Genesis 1-11, which has just been published with a foreword by Bishop Robert Vasa of the Baker Diocese in Oregon. Bishop Vasa has this to say about Fr. Victor’s work:

The Doctrines of Genesis 1-11: A Compendium and Defense of Traditional Catholic Theology on Origins, by Reverend Victor P. Warkulwiz, M.S.S., is a wonderfully researched and thoroughly stimulating work. Father Warkulwiz, drawing on his very substantial scientific background, walks us through the early chapters of Genesis showing and giving testimony to the essential compatibility between the literal account of Genesis, the understanding of the Fathers of the Church and the modern day observations of natural science.

He very cogently points out that many of the accepted scientific conclusions which contradict the days of creation and the great flood are based on a variety of unproven premises which are pillars set firmly on sand. Father very adeptly tackles the complex issues of cosmogony, astronomy, astrophysics, mathematics, nuclear science, evolutionary theory, geological uniformitarianism, radiocarbon dating, big bang theory, and others to show that the observed phenomena which they try to explain are just as readily, properly and easily explained by such Genesis factors as direct creation by God and the Genesis Flood. In doing so he opens a clear path for dedicated Christians to read the Book of Genesis with a renewed and, to a certain extent, unencumbered faith.

Dr. Dean Kenyon, Ph.D. Biophysics, and formerly one of the leading evolutionary biologists in the world, writes that Fr. Victor “brilliantly demonstrates that the relevant results of modern science, rightly interpreted, are much more consistent with the traditional Catholic view of origins than they are with macro-evolutionary theory.” And Fr. James Anderson, Ph.D., Philosophy, and former Academic Dean of Holy Apostles College and Seminary, writes that Fr. Victor’s “scholarship is first rate and his argument is incisive. This book is a must for scholars, students and laymen.”

This is a book that can change the way that Catholic bishops, pastors, and teachers think about origins. It is a book that can do more to restore the traditional Catholic understanding of origins and human history than perhaps any book written in the past 60 years. Although expensive (roughly 560 pages, $32.95 + shipping), it is a book that ought to become a standard reference for every Catholic home, seminary, college, and high school. Please help to promote this book in your parish and community. Please pray that through the prayers of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Maximilian Kolbe, Fr. Victor’s book will cause great numbers of bishops, priests and lay people to return to the traditional Catholic understanding of Genesis, the foundation of the Gospel.

May the Lord Jesus find a blessed home in your hearts this Christmas and always!

Yours in Christ,

Hugh Owen, Director Kolbe Center for the Study of Creation

Anyway, all of this stuff makes a darn good case. But it’s not alone. Back in 2006 I tracked down in the microfiche the original source of a series of short 1980 newspaper articles on a controversy at San Francisco State about Dean Kenyon teaching creationism in his evolution class. The first story (and the longest) appears to be a December 17, 1980 story in the San Francisco Examiner (now a free daily, but back then a standard newspaper).

And the article is – well, by itself it proves the case. Strangely, though, this history was never mentioned in any of the 1990s ID movement literature glorifying Kenyon as a scientists who saw the light and became an ID proponent, leaving out the 10+ years of his being a creation-science proponent before that. The only mention of this anywhere in ID-sympathetic literature is the following oblique mention by Larry Witham, a journalist who wrote a rosy and pretty naive history of ID in 2002 (which nevertheless dropped many interesting tidbits derived from interviews):

As Biochemical Predestination was published, Kenyon spent the 1969-1970 academic year on a fellowship at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, where he reviewed the contemporary literature on the relationship of science and religion. As an Episcopalian, he was not inclined to see any conflict between God and Darwinism. Yet this was for him a season of intellectual doubt. In the mid-1970s, a student gave him a book that challenged the idea of purely chemical origins of life: The Creation of Life: A Cybernetic Approach to Evolution, by European creationist A.E. Wilder-Smith. Kenyon made time during the summer for what he thought would be a handy refutation of the work. “I found out, in fact, I could not answer the arguments,” he says. Thus began a period of “serious personal rearrangement of thought and anguish of the soul” that took him up to the 1980 fall term. He was a tenured professor [he got tenure in 1970 – Witham 2002, p. 163], and he had to make a decision.

“Just go public with my doubts? Take my chances?” He asked himself that question, then proceeded to do just that, perhaps naive about the consequences that would follow when a few students complained about his comments in class. The story would make the San Francisco Examiner. “Well,” Kenyon says, “I had no idea of the fallout.” He was summoned to three faculty hearings to testify on what he taught in his courses. Department chairman William Wu responded by laying down the “5 percent doctrine”: no more than 5 percent of a course could include criticism of or doubts about Darwinian theory, and that was how Kenyon proceeded through the 1980s.

(Witham 2002, Where Darwin Meets the Bible, pp. 163-164).

Hmm, so the controversy in 1980 was about “criticism of or doubts about Darwinian theory”, and throughout this passage and the book, Witham takes pains to make it seem like ID is disconnected from creationism.

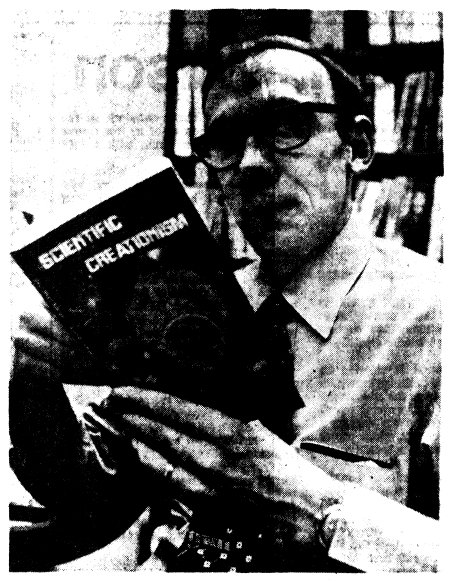

But check out the actual article in the SF Examiner. The photo is particularly good. PDF download. Text below for posterity. Posting this is fair-use under copyright law, as I recently learned at a talk on copyright that not only is this academic, nonprofit use, but posting a single article is reproducing only a portion of the work (the “work” in copyright law being e.g. an entire journal, volume, etc.)

[Reference]

Salner, Rebecca (1980). “Professor teaches a supernatural creation of world.” San Francisco Examiner, p. zA-9. Wednesday, December 17, 1980.

[Article text]

[transcribed by Nick Matzke, 10/29/06]

‘The. better scientific model is the creationist one. Evolutionary view has too many inconsistencies’

Professor teaches a supernatural creation of world

By Rebecca Salner

Dean Kenyon is a soft-spoken, serious and sincere man who teaches evolution at San Francisco State University.

But he doesn’t believe in evolution. He believes in God and scientific creationism – an alternative theory which parallels the biblical story of creation.

Kenyon has taught the biology department’s only evolution class for 12 years. For eight of those 12, he was a believer in macro evolutionary theory as were the vast majority of his colleagues.

They haven’t changed. He has. Four years ago, after “technical evidence” convinced him that evolutionary theory was incorrect, he began including scientific creationism in his course and drawing criticism from those whose beliefs he once shared.

Kenyon defines the main tenet of scientific creationism this way:

“In the relatively recent past – 10,000 to 20,000 years ago – the entire cosmos was brought into existence out of nothing at all by supernatural creation.”

According to Kenyon, gaps in the fossil record and the lack of evidence documenting transmutation of species strongly support creationist views.

The fossil record is posing the greatest problem for today’s evolutionists, says Kenyon:

“Rather than exhibiting trends, the fossil record gives a picture of stasis and then gaps.” (Stasis is the existence of species over long periods of time without change.)

Creationists theorize that fossils and rock strata formed during a worldwide flood, not over billions of years as evolutionists believe.

“Holes are characteristic of evolutionary theory,” he says. “The better scientific model is the creationist one. Evolutionary view has too many inconsistencies.”

One of Kenyon’s most outspoken critics on campus is Professor Lawrence Swan, who calls creationism “embarrassing.”

“How can an institution of higher learning permit the teaching of an aberrant misinterpretation and what I would consider an intolerable representation of the truth?” asks Swan. “What we’re faced with is a very interesting intellectual morass. What do you do with a professor who has gone wrong?”

For Swan, academic freedom is no defense for teaching creationism.

“If this is academic freedom, almost any bucket will go in. I can talk absolute nonsense to my class.”

“Do geologists allow a flat-earth advocate to teach? Would astronomers like astrologists? But this (creationism) differs because the evidence for it is not scientific, it is religious. Does a professor have the right to teach anything he wants? Can society afford to deny science?”

Creationists’ attacks on the holes in evolutionary theory enrage Swan who claims they employ a “You don’t know, therefore God” argument.

Douglas Post, professor of ecological and systematic biology, agrees, saying, “I don’t think there is any positive evidence to prove creationism. They rely on negative evidence. Their main argument is that you can’t prove that Darwin is correct. But I don’t think that just because you can’t prove Darwin you can automatically conclude that creationism is correct.”

Kenyon denies the religious base of his group’s evidence and says creationism is not a “God of the gaps” theory.

[photo] [Photo of Dean Kenyon holding up the book Scientific Creationism by Henry Morris (looks like the General Edition).]

[/photo]

[caption] Biology professor Dean Kenyon’s controversial course seems to be well-supported among the students [/caption]

“Our evidence is of the same status as that used by evolutionists. We talk about fossils, rocks, animal species…”

“One of the creationist’s points is to say this is not religious,” says Swan. “That’s malarky. The major premise is the first chapter of Genesis. It’s an argument, an old argument, between trying to understand what’s natural versus the miraculous.”

None of the professors in the department have expressed much support for creationism, although a few have said the issue is “interesting.”

Department Chairman William Wu also believes the theory is religiously based.

“Having listened to Dr. Kenyon on one side of the coin and some of our evolutionists on the other, I have to tend to agree with it being biblical. It fits.

“Any person who has gone to Sunday school will immediately grasp the similarity. But in fairness to scientific creationism and to Dr. Kenyon, Dr. Kenyon believes that the Bible should not be brought into it.”

Kenyon admits a connection between religion and creationism but holds fast to the belief that religion does not enter the classroom.

“If you’re not familiar with the technical literature you may think that Genesis is being taught. It is quite a radical departure from what most of our faculty learned in graduate school. It takes a lot of effort to change that. Any line of thought which tries to figure out ultimate origins will come into areas of religious thought,” says Kenyon.

Although he may not bring religion into the classroom, Kenyon personally is religious and believes there are “no errors in the Bible.”

In 1969, he took a leave of absence from the university to attend the University of California at Berkeley’s graduate theological union. Five years later he attended Trinity College at Oxford to work on a project titled “The Reception of Darwinism by the Church of England.” On his desk is a plaque proclaiming, “In Christ are hid all the treasures and knowledge.”

Kenyon, 40, is a quiet, scholarly man customarily clad in a professorial tweed blazer and conservative gray slacks. His students like him and even circulated a petition supporting his inclusion of creationism in the course.

He seems genuinely surprised at the violent reaction of some faculty and one or two students. And though he appears to be the only creationist under fire, he claims there are others on campus – three at least, but he won’t say who.

Even Swan, his critic, says Kenyon is “a very sweet, gentle, quiet, somewhat convincing man.”

Only two professors contacted were remotely supportive of Kenyon’s theory.

Sarane Bowen, a specialist in cell and molecular biology, said the issue makes the department’s course offerings more interesting.

Charles Hagar, physics and astronomy, said, “I think it’s very nice to shake up the basket and see what goes on. I’m always in favor of controversy. I think that’s how science progresses. All too often, evolution has been presented as fact and it’s kind of interesting to see that challenged by alternative theories. If they’re wrong, let the scientists knock them down.”

Kenyon has been asked to hold discussions of creationism to 5 percent of class time – a guideline developed by Chairman Wu, who said Kenyon is not policed, although a faculty member is auditing the class.

Wu believes the issue of Kenyon teaching creationism is resolved.

Swan and Kenyon want further discussion of the matter, and believe it is unresolved.

Swan would prefer that Kenyon not teach creationism, or, if he must, at another university.

Kenyon wants more time given to creationism.

“If I were to dream about it, I would say a 50-50 split” between evolution and creationism, says Kenyon.

PS: Here is the 1972 article I found (also back in 2006 I think) on Smith & Kenyon’s idea about de novo origin of viruses:

Winnipeg Free Press, Wednesday, March 22, 1972. p. 43

Prof Flips Theory Coin About Virus Production

MONTREAL (CP) - Man may be a walking virus-maker, says Adolphe Smith, a 43-year-old biophysicist and professor at Montreal’s Sir George Williams University.

In an article to be published in an international journal of microbiology, he and Dean Kenyon of San Francisco State University flip the coin of the current theory that viral infections are caused solely by germs invading the body when resistance is low.

At least some of these infections are caused by viruses produced within, the body after it has undergone damage or stress from the environment, they contend.

Viruses are infectious agents that reproduce in living cells.

“Since Pasteur, man has gone overboard in thinking germs come from outside,” said Dr. Smith in a recent interview.

However, he and his colleague do not discount external factors in the cause of viral infections such as influenza and apply their theory only to “latent” or non-contagious viruses.

He used the example of a cold sore.

“You have a recurrent infection at the same place but in between occurrences it is impossible to detect the presence of a virus – so the virus must come from within.”

According to Dr. Smith’s theory, environmental stress causes some cells to change into viruses and under certain conditions these viruses appear.

“This stress could come from poor living conditions or polluted air which damage the lungs,” he said.

That points to a need for a cleaner world.

“If stress from the environment does produce viruses in the body, then we must reduce this stress by cleaning up the environment,” said Dr. Smith.

“What I am saying, in effect, is that the environment is not just a factor, but the factor.”

Anti-pollution groups are making a great stride in preventive medicine because they are trying to improve the environment which plays such a great role in determining man’s health, he said.

Note: I had to hand-transcribe these articles to text; I caught a few mistakes today, but some typos may remain.