Evolution's Witness: book review

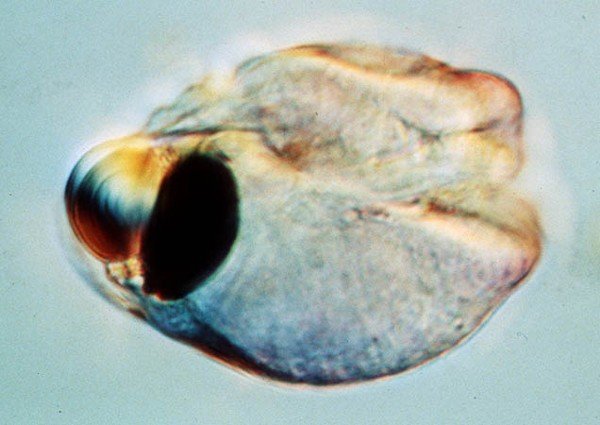

Who knew? A single-celled organism has a camera eye with a lens. A certain fish has two corneas and controls the intensity of light on its retina by injecting pigmented particles between them. Other animals can shield their rods (the receptors for low intensity) during the day. A conch can grow a wholly new eye. A flatfish has both eyes on the same side of its head, but starts life with bilateral symmetry. A sea snake has a light sensor in its tail to ensure that the tail is hidden under a rock. Some birds cram their corneas through their irises in order to focus on nearby objects under water. The woodcock can see behind its own head - in stereo. Some animals have two foveas in each eye, one for peripheral vision and one for binocular vision.

If you find any of those facts interesting, then you must read the new book, Evolution’s Witness: How Eyes Evolved, by Ivan Schwab, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of California at Irvine. It is a wonderful book, truly encyclopedic, and chock-full of high-quality color photographs and fascinating examples and explanations. Many of the photographs, I suspect, were taken by the author or other people in his own lab, but others were contributed by surprisingly many researchers worldwide. There is practically nowhere where I thought, “I could really use a figure here,” except occasionally when I would have welcomed a line drawing.

I knew about the flatfish before I read the book. I remember once mentioning to a friend of mine, as he was about to eat a dead flounder, that both eyes are found on the same side of the head, and the flounder lies on the bottom and swims with a vertical undulation. He did not believe me, but my wife convinced him that I was not joking (evidently, I have a bad reputation). She in turn did not believe me when I noted that the fry (baby fish) were born with bilateral symmetry and swam normally. Also true. But that is not all: In order to accommodate the metamorphosis to the adult stage, says Schwab, the pathways in the brain have to change, and “[i]t is almost as if the eyes retained their position and the body of the fish rotated beneath them,” so vision, not structure, is apparently paramount. Further, the fry are born with one kind of cone, but the adult flatfish develop rods and three different kinds of cone during their metamorphosis. Armed with color vision, the adults can now change their skin colors slightly to match the color of the background.

The book is organized by geological epoch and shows how eyes evolved from a simple, light-sensitive spot to a dazzling array of eyes based primarily on the compound (or fly’s-eye) lens or the camera eye. What was most interesting to me, though, was how every type of eye evolved to secure its owner’s niche in the environment and also how similar problems were solved over and over with different solutions. Our mammalian ancestors, for example, descended from animals that had four different kinds of cone: red, green, blue, and ultraviolet. Most mammals eventually lost two of the cones, leaving red and ultraviolet. Presumably when primates became diurnal, they developed three-color vision, probably by duplication of the gene for red, and the ultraviolet cones drifted toward blue. They thus solved the three-color problem by taking what was already there and modifying it substantially. Evolution uses what it has, not what it needs or what we might think it wants.

The book is generally clearly written and organized. Explanations are terse and to the point, and make good use of the figures. Many if not most descriptions are by example; the book is interspersed with short, italicized segments describing the optical systems of various organisms. Additionally, a relatively few explanations are set off in boxes. At first, I found this technique confusing, but I very shortly grew to appreciate it. I also enjoyed the occasional witty aside, as when the author describes the eye of a certain copepod, which is found only in the male and is apparently used to recognize the female: “So, although small, this copepod carnivore holds visual secrets with an eye for the ladies.”

I noticed a few minor errors or misstatements in some of those areas in which I actually know something. Diffraction does not occur only when the diameter of an aperture is comparable to the wavelength of light; in fact, all lenses with the same F-number have the same diffraction limit. The lens of the tuna does not exhibit spherical aberration because it is wide open, but because it is a large lens with a long focal length (spherical aberration scales with focal length, whereas the diffraction limit does not). Large eyes do not have greater light-gathering power (though they have greater magnification and therefore greater resolution); light-gathering power depends only on F-number. I would not call a stippled surface aspheric, and unless I misunderstood the context, the stipples must be one-quarter, not one-half, wavelength high. Brewster’s angle is not the critical angle. In one description, I thought scattering was confused with chromatic aberration. None of these quibbles detracts from the usefulness of the book.

I could have used more explanation in a very few places. Why do certain organisms have noncircular pupils? The one explanation of a pupil that closed down to a number of pinholes for depth perception was unclear, at best. How does a colorblind cuttlefish adjust its own color to match the background? Why does the size of the eye vary with speed? How does a fly’s-eye lens form an image?

The technical editor in me notes that the volume is generally well edited. But I did not like mixing full spellings and SI (International System of Units) symbols, as in “100 meters” and “10 cm”; “100 meters,” should have been “100 m.” Likewise, “10 km an hour” should have been “10 km/h,” and “8000/mm2” should have been “8000/mm2.” The SI symbol for the second is s, not sec: you can get no secs in SI. “Ago” is not an SI unit, and “m” stands for “milli-,” so I do not accept the common notation “mya” for “million years ago”; at the very least, the m (for mega-) should have been capitalized. And, finally, the unit of velocity is the knot, not the knot per hour.

The book is extremely well prepared and exceptionally well illustrated with countless photographs - at 22 by 28 cm, practically a coffee-table book. You could get by by reading only the figures and captions, but you would be missing a lot. Yet much of the book was too technical for me, a nonbiologist. In spite of the excellent glossary of terms, I remain baffled by a few of the explanations. For example, I had to resort to the Web to be certain how many axons emerge from a single ommatidium (the photosensitive element in a fly’s-eye lens).

In short, I felt at times like the seventeen-year-old boy who told Umberto Eco that “he understood nothing of the theological arguments, but they acted as extensions of the spatial labyrinth (as if they were the ‘suspense’ music in a Hitchcock film).” No matter; the boy enjoyed Eco’s novel, and I was fascinated by Schwab’s book.