A superb new fossil from Dmanisi, Georgia

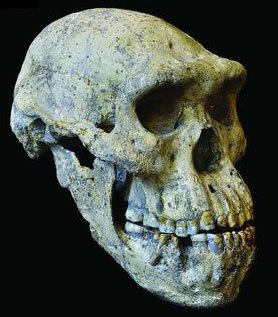

A new paper was recently published, and widely reported in the media, about a hominid skull discovered at the Dmanisi site in Georgia in 2005 (Lordkipanidze et al, 2013, Gibbons 2013). The fossil, D4500, is believed to belong to the same individual as a lower jaw fossil, D2600, previously found at the site. The combined skull, designated by the authors as “Skull 5” (the 5th skull from Dmanisi) is almost completely and perfectly preserved, making it one of the most spectacular finds in the entire hominid fossil record. And Dmanisi is rapidly becoming one of the most important sites ever found in the study of human evolution.

Skull 5’s brain volume of 546 cm3 is very small. The other Dmanisi skulls are between 600 cm3 and 730 cm3. (Earlier papers gave the size of the largest one as 780 cm3, but that estimate appears to have been reduced. By comparison, the average modern human brain size is 1350 cm3.) However the fossil also has a large and robust jaw bone, and a large and projecting face. This combination of a very small brain and a large face differs from all other known Homo fossils. The fossil is of a mature adult, and because of the robustness of the skull it is thought to belong to a male.

Scientists are naturally delighted at the discovery of such a superb fossil, but the real impact of Skull 5 comes from the conclusions that the authors have drawn from it.

The Dmanisi fossils are different enough from each other that had they been found at different locations, they might have been classified into different species. Similar differences have been used to create species such as Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis in the past. The authors believe that the Dmanisi fossils all belong to one species, both because they all come from the same time and place, and because the pattern and amount of variability found between the skulls is similar to that found in populations of modern humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos.

Following that line of reasoning, they conclude that since a similar pattern of variation exists for all early Homo fossils in Africa, and in the absence of any evidence that the supposed different species of Homo were adapted to different ecological niches, the default and most parsimonious assumption should be that all of these fossils belong to a single highly variable lineage (though they recognize that this claim remains to be tested, and alternative scenarios exist). This would mean that Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo ergaster and some other more obscure names did not really exist as separate species. The name of that single species would, for reasons of priority, be Homo erectus. Specimens allocated to H. ergaster would then be called Homo erectus ergaster, as a time-limited subspecies. The Dmanisi scientists had previously named a new species, Homo georgicus, for the Dmanisi fossils, but now retract that name and suggest that because the Dmanisi fossils arose from an ergaster population, they should be called Homo erectus ergaster georgicus.

Most scientists appear to accept the claim that all the Dmanisi skulls all belong to the same species, but even that is not a given - Ian Tattersall of the American Museum of Natural History, for example, believes that Dmanisi could include more than one species, and that Skull 5 could be a new species (Gibbons 2013). And Donald Johanson, the discoverer of Lucy, disagrees with the Dmanisi scientists on one of their points, and argues that

the entire collection of specimens of early Homo species from East Africa shows “considerably more variation than you see in this sample [from Dmanisi], which is not surprising, because you’re looking at fossils from very different regions.”

He, and a number of other scientists quoted in various online articles, either disagree with or are still withholding judgement on whether all early Homo fossils should be merged into Homo erectus. For example Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London believes the Dmanisi scientists may well be proven right that some early Homo fossils could join a variable Homo erectus, but doubts that all of them will, given the vastness of Africa, the depth of its fossil record, and evidence of species-level diversity prior to two million years ago.

If the Dmanisi scientists win the day on this argument, it really will be a significant change in the way that scientists view the details of the history of human evolution. If nothing else, it will certainly be a shot in the arm to the multiregional model of human evolution, which in recent years has fallen out of favor compared to the competing Out-of-Africa model.

What have creationists had to say about this skull?

Not much. The young-earth creationist organizations Answers in Genesis and the Institute for Creation Research seem to have ignored it, but a couple of Intelligent Design sites have addressed it.

This is the reasoning in an extraordinarily clueless article from Uncommon Descent:

News wrote:

Here’s the kicker: The level of variation between the skull remains at Dmanisi could well be matched among modern humans waiting for the bus in a multicultural city.

What makes the find controversial is that much ideology around human evolution depends on a variety of not-quite-human species that once walked the Earth (but one rose above its fellows or prevailed over them). If there is no real evidence for more than one human species, ever, well, the unity of the human race is more consistent with traditional non-materialist assumptions than modern materialist ones.

Even if there is no evidence for more than one Homo species at any given time, that doesn’t mean that that species has stayed static though time. And if there was only ever one Homo species, it clearly has changed through time, rather dramatically. Even though the Dmanisi fossils show quite a bit of variability, none of them comes close to being looking like a modern human skull, and no modern humans look like, or are found at the time of, the Dmanisi fossils.

The claim that human evolution “depends” on having multiple species is also nonsense - it doesn’t require multiple species for evolution to happen. As the Dmanisi authors explictly pointed out:

Lordkipanidze et al. 2013 wrote:

The hypothesis of phyletic evolution within a single but polymorphic lineage raises a classificatory but not evolutionary dilemma … (my emphasis)

And quite why anyone would think that the similar level of variation of the Dmanisi fossils and modern humans is a “kicker” is a puzzle. One might find a similar level of variations in populations of mice and capybaras too, but I don’t think creationists would argue for “the unity of the rodent race” as a consequence.

The News writer appears, in arguing for “the unity of the human race”, to be suggesting that the Dmanisi fossils are actually human. If so, he/she should perhaps ponder why it is that the Dmanisi fossils look so much more similar to australopithecine fossils than they do to modern humans.

Casey Luskin’s article at Evolution News and Views is hardly any better. There is little explanation of the significance of the Dmanisi fossils, and what there is mostly comes from the lengthy quotes he included. He misrepresents Donald Johanson by claiming that that he “disagree(s) that these [Dmanisi] skulls all represent one species”, when what Johanson actually did was to express doubt that all early Homo fossils should be merged into Homo erectus. Luskin has adopted a “small target” (indeed, “microscopic target”) strategy. Although he makes plenty of criticisms, and drops in words like “spotty”, “sketchy”, and “gap(s)” as frequently as possible, he avoids saying anything about how the Dmanisi fossils should be classified. He says that the qualified statements of scientists “hardly inspire confidence”, though if they had made confident assertions I’m sure that he would have complained about that too. Luskin may like to talk about “gaps”, but look at Figure 4 from the Dmanisi paper:

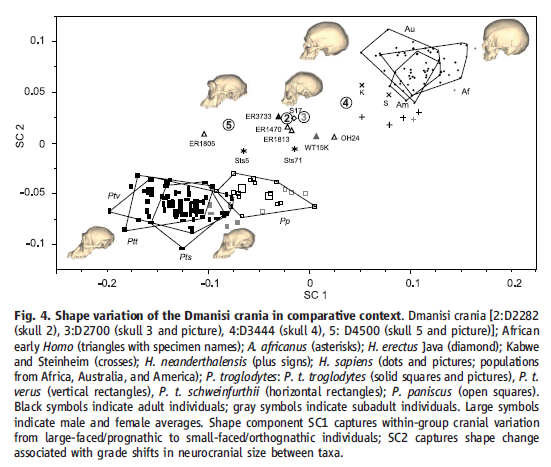

The horizontal axis of the chart goes from projecting (prognathic) faces on the left to vertical (orthognathic) faces on the right, and from small brains on the bottom to large brains on the top. Modern humans are in the polygons on the top right; chimps and bonobos are in the polygons on the bottom left. There certainly is a sizable gap between modern apes and humans. The trouble, for Luskin, is that it is filled with specimens from the hominid fossil record. In particular, the Dmanisi skulls (the circles containing the numbers 2, 3, 4, and 5) are scattered fairly widely throughout that gap. Luskin has, in the past, argued that the Dmanisi hominids are apelike, but he was only able to make that claim by dint of serious cherry-picking and misrepresentation of the evidence.

So my question for Casey Luskin is: you claim there is a gap between humans and apes. If so, this should be a really easy question to answer: on what side of that gap do you classify the Dmanisi fossils?

The Dmanisi fossils, and other similar fossils from Africa are very powerful evidence of creatures that are transitional between earlier apelike creatures and modern humans. This remains the case regardless of how many species all these specimens are classified into.

Further reading

Paleoanthropologist John Hawks has a long and thoughtful post: The new skull from Dmanisi.

Science writer Carl Zimmer: Christening the Earliest Members of Our Genus has an interesting discussion of population structure in widespread species/groups of species, and points out that resolving such questions can be difficult even for modern groups for which we have vastly more data than we will ever have for fossil humans.

References

Gibbons, A. (2013): Stunning skull gives a fresh portrait of early humans. Science, 342:297.

Lordkipanidze D, Ponce de Leon M. S., Margvelashvili A., Rak Y., Rightmire G.P., Vekua A., Zollikofer C. P. E. (2013): A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo. Science, 342:326.

Previous Panda’s Thumb posts about the Dmanisi fossils:

Dmanisi skulls and creationism (2005)

Dmanisi fossils - more transitional than ever (2008)

Dmanisi and Answers in Genesis (2008)

Dmanisi in the news (2009)