"The Monkey's Voyage" Will Take You on a Voyage Through a Biogeographic Revolution

Note: this is an off-the-cuff review that I wrote while experiencing jet-lag induced insomnia (I am in Canberra, Australia, to give a workshop on BioGeoBEARS at the 2014 meeting of the International Biogeography Society at Australia National University). I have a more formal review in preparation for the Reports of the National Center for Science Education.

Note: this is an off-the-cuff review that I wrote while experiencing jet-lag induced insomnia (I am in Canberra, Australia, to give a workshop on BioGeoBEARS at the 2014 meeting of the International Biogeography Society at Australia National University). I have a more formal review in preparation for the Reports of the National Center for Science Education.

Review of: de Queiroz, Alan (2014). The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped the History of Life. Basic Books: New York, pp. 1-348. http://themonkeysvoyage.com/ - Amazon Link

Today, a book is coming out that is destined to become a classic of science writing. Normally, popular science books popularize well-established science. The research being popularized may be decades or centuries old. Certainly popularization of such material is important, but I found that for me, the appeal of such works dropped off as I matured as a scientist. There are only so many times you can read about Darwin and the Beagle, or Laplace and the hypothesis he had no need of, or the sequence from Mendel to Watson and Crick, before you feel like you’ve heard it all before and it ceases to become interesting.

Alan de Queiroz is doing something different. He is popularizing an active scientific controversy in biogeography. Biogeography is the science of where species live and how they got there. The biogeographical controversy is termed “dispersal versus vicariance,” and it runs long and deep. Understanding what the controversy is about, and why anyone would care, takes a little bit of background.

Background: The History of Historical Biogeography

Basically, the issue is this: Darwin and Wallace’s discovery of evolution clarified a great many puzzles in biogeography. They pointed out that, if it is true that new species came about by descent with modification of older species, then we can understand many biogeographical phenomena that were quite puzzling under the paradigm that God specially created the species. For example, volcanic islands far from continents are (natively) devoid of amphibians, terrestrial mammals, earthworms, and many other organisms common on continents. If the deity were poofing species into existence in appropriate habitats, there seems to be no particular reason for Him to have excluded volcanic islands. However, on the theory of evolution, we have a ready explanation – anything that lives on remote volcanic islands had to get itself there by some physical means, some time after the volcano erupted out of the ocean. Organisms that can float in saltwater for long periods of time (tortoises, coconuts) are commonly found on such islands, as are birds and organisms that hitch rides on them. But organisms with poor abilities to disperse over salt water – such as as worms and amphibians – are not on those islands, because they could never get there.

Descent with modification also explains why species in the same genus tend to cluster on the globe, rather than being evenly distributed everywhere. Quite often, this geographical clustering occurs irrespective of quite different environments – many of the desert flowers in California look like modified versions of nearby flowers of grasslands and chaparral. Deserts on different continents tend to be populated by succulents related to other plants on the same continents – cacti are ubiquitous in the deserts of North and South America, but there are no native cactus in Africa or Asia (there is one peculiar bird-dispersed form in Madagascar).

This is all well and good, but in solving many puzzles, descent with modification created some new ones. In particular, there are organisms on the globe that are obviously related, and living on continents, but are on opposite sides of oceans. Some of the famous ones are the ratite birds of the Southern Hemisphere (ostriches, rheas, kiwis, the extinct moas of New Zealand and Elephant Birds of Madagascar, etc.), and the Southern Beeches of the genus Nothofagus, distributed in temperate forests in South America, New Zealand, Australia, New Caledonia, and New Guinea. The debate over the biogeography of these clades extends back to Darwin and his contemporaries. Darwin was an advocate of dispersalism, arguing that on rare occasions, oceans could be crossed by poor dispersers – perhaps, for example, if some dirt and seeds fell on a glacier, and the glacier calved off an iceberg, and the iceberg crossed the ocean and ended up melting on a foreign beach…can it be said that such a thing is impossible? Hooker, on the other hand, favored “land bridges” as an explanation for close cross-ocean similarities, especially when the similarities extended to whole floras. The idea here is that two regions with similar floras used to be contiguous, and then were broken up by environmental change forming a barrier – for example, the sinking of a land bridge. Contiguous ranges followed by breakup constitute a “vicariance” explanation.

Which is correct? Darwin thought land bridges were invoked in far too carefree a fashion, and the geological support for them was often dubious. Hooker and others thought similarly of near-miraculous dispersal mechanisms. The debate has continued since then. Until the 1950s, the dispersalist school was probably dominant, in part because most geologists believed in the fixity of continents, and the evidence for land bridges was usually weak. However, with the acceptance of continental drift, the tide turned. Biogeographers finally had their overland connections, albeit in a different form than originally conceived. The advance of plate tectonics happened to coincide with the advent of cladistic methods for inferring phylogenetic relationship, starting with the work of Hennig. Cladistic methods relied on atomizing organismal morphology and traits into discrete character states, and then searching for trees that minimized the number of character state changes in homologous characters (parsimony).

Vicariance Biogeography: Advance or “cul-de-sac”?

Similar methods were soon applied to historical biogeography. Geographic range was discretized into a series of presences and absences for each species. These could be used to attempt to reconstruct the geographic history of an individual clade, but the more interesting application was to use biogeographic distributions to reconstruct the history of connections between areas. Here, the geographical areas become the lineages, and the presence or absence of particular clades constitute the character states. This approach favors vicariance, as clades sitting still are the “homologies”, and dispersal events become homoplasies. The best tree of areas is the one that maximizes vicariance explanations, and minimizes dispersal; it was then assumes that this represents the history of breakup of areas.

This extension of cladistic methods and vicariance assumptions to biogeography – vicariance biogeography – was conceptually appealing: researchers could calculate support statistics like they did for cladograms; the general area cladograms that resulted told an interesting synthetic story, and, for once, it seemed like the biogeographers might be able to help the geologists reconstruct plate histories. However, there were always some major open questions. The first concerns homology. A parsimony analysis of organismal characters relies on the assumption that shared character states for a particular character are, on average, more likely to be shared because of common ancestry (shared history) than because of convergence (independent acquisition). This assumption does not have to be true for all characters analyzed, but it should hopefully be true for the majority of them, or, at the very least, the signal of shared history should be more common in the characters than any other directional signal. These assumptions are eminently reasonable for a diverse set of distinct organismal characters. However, in the biogeographical case, when all of the characters are clade presences in regions, these assumptions require that vicariance be a more probable explanation than independent dispersal. This could be true, but it is an assumption.

Another assumption that is made in this operation is that the age of clades doesn’t matter. The inputs to vicariance biogeography methods are simple cladograms, which do not come with time scales unless they are added. This was perhaps unavoidable in the 1970s and 1980s when cladograms were the typical result of phylogenetic analyses, but nowadays, time-scaling, ideally using the fossil record, is a standard procedure. Two clades might have the same geographic distribution, say, ABC (living in areas A, B, and C), but if one clade is 5 million years old, and the other is 100 million years old, it is hard to argue that they are evidence of a common geological history of those three regions.

Whatever the validity of the assumptions, for many years, vicariance biogeography methods were the only phylogenetically explicit methods available. This is still largely the impression you will get if you visit the biogeography shelf of a university library. And, for reasons that remain somewhat obscure to me, the above assumptions were applied not just to reconstructing the history of areas, but often, to reconstructing the history of single clades. I can see why the assumptions might be useful if the goal is reconstructing the history of geographical areas using cladistic methods, because some assumptions about “homology” and shared history need to be made to even get started; but when the same assumptions are applied to reconstructing the history of individual clades, what results is a method that assumes “maximum vicariance” – vicariance is employed as the preferred explanation of distributions wherever possible.

Some biogeographers never bought this assumption – especially biogeographers who worked on island taxa where dispersal seems overwhelmingly likely to be the major explanation of distributions. But, probably because of the power of the twin revolutions of plate tectonics and cladistics – and the fact that both revolutions, at least according to common legends, took over in the face of hardened opposition from hidebound proponents of orthodoxy in the academic establishment – there are still many biogeographers who repeat the line that dispersal is an unscientific explanation that can be used willy-nilly to explain any distributional data, and that historical biogeography should be focused on detecting the signal of vicariance.

The last 15 years have seen the explosion of phylogenetic dating methods, as well as many new computational methods for analyzing biogeographical data on phylogenies. This has diluted the classic old dispersal-versus-vicariance debate somewhat, such that when the issue is raised, many will say something like: “Oh, that old chestnut. I’m tired of that debate, clearly the answer is that both happen and both are important. It’s a false dichotomy.” Actually, I am convinced this is a wrong and frankly somewhat lazy answer, for reasons I will explain at the end of this review.

At any rate, even if the dispersal versus vicariance debate seems old-fashioned, it is definitely not dead. One piece of evidence for this was the book Molecular Panbiogeography of the Tropics by Michael Heads (2012). This large tome, published by by the respected University of California Press, analyzes the biogeography of hundreds of clades from around the world, but does so with a rigid application of the assumptions of vicariance biogeography – Heads mostly ignores molecular dating results, even though many of the phylogenies he makes use of come from papers that apply dating methods, and furthermore, he states clearly that one of his starting assumptions is that long-distance dispersal (or “jump dispersal”) will not be used in his reconstructions of the history of clades.

de Queiroz Enters the Fray

The other piece of evidence is Alan de Queiroz’s new book, The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped the History of Life, published on January 7, 2014. de Queiroz takes aim at the vicariance school in biogeography and argues that its proponents “ended up arguing themselves into a strange intellectual corner where they envisioned an idealized history of life that never was.” He says that vicariance biogeography was “a turn down an intellectual cul-de-sac” for biogeography, and that this group’s systematic skepticism about phylogenetic dating indicates “an acute disconnection from reality related to this skepticism about the estimated ages of groups.”

de Queiroz begins his defense of these statements with a thorough introduction to phylogenetic dating methods – definitely the best introduction to the methods that I have seen written for the general public. By telling the story of his own work and many other modern researchers, he brings to life how the dusty old vicariance biogeography debate played out in the work of individual researchers trained in that tradition. In short, as DNA sequencing became ubiquitous, high-quality phylogenies could be constructed for any living group of interest. Dating methods, some relying on the molecular clock, but many others relying on less restrictive assumptions and fossil calibrations, kept giving results that indicated that many divergence events were just too young to be explained by classic vicariance hypotheses. Worse, the biogeographic congruence of different groups that researchers sometimes thought they saw through the blurry lens of Linnaean taxonomy or undated cladograms often fell apart once dates were available. Despite all of the caveats of dating methods – high uncertainties, difficulties in finding reliable calibrations, the fact that the oldest fossils in a clade are never the oldest true members of a clade that existed, etc. – caveats which de Queiroz reviews well – the overall picture seems robust. Relatively few clades and inferred biogeographic events inferred from the dated phylogenies of living taxa are old enough to be explained by continental breakup. Often, the only way to make an analysis say that clades are sufficiently old is to use the postulated continental breakup to set the date of divergence; but this rather puts the cart before the horse, and often indicates molecular rates far slower than those indicated by much other evidence, and puts the divergence times far, far below those indicated by the fossil record of the group in question.

The discussion of dating results is the intellectual core of the book, but de Queiroz successfully combines a scientific review with an engaging journalistic style, complete with humorous asides and witty quotes from the participants. Michael Donoghue’s ultra-laid-back, but devastating, assessments of the vicariance school, and his description of his own personal journey from interest in the methods to concern at their rigidity, is not to be missed.

de Queiroz supplements the scientific argument with a capable review of the history of historical biogeography, complete with quotes and stories from the main players, many of whom are still alive (and definitely kicking). The tale of how a subfield can manuever itself into what seems like, from the outside, a quite odd intellectual position, is interesting in and of itself, and serves as a caution to all of us in this age of scientific super-specialization.

de Queiroz also effectively analyzes just what it was about vicariance biogeography that made it so appealing to so many. The role of plate tectonics and cladistics was described above, but he covers the popular appeal as well. Probably every reader has been to a zoo or museum, seen one of those amazing animations of continental plates moving about the globe, and read some description of the biogeography of some clade (usually ratites or southern beeches) and how it is neatly explained by plate tectonics. The simplicity of the story is gripping – first a puzzle (cross-ocean distributions), followed by a resolution a fifth-grader could understand, namely, the (admittedly amazing) reconstruction of the history of plate movements. de Queiroz notes that even beyond this, there is probably more than a little regional pride behind the appeal of vicariance explanations. Standing in a primeval forest in New Zealand is all the more appealing if you think that you are basically standing in a forest that has existed in its present form since the Mesozoic.

Finally, de Queiroz makes the positive case for dispersal, not just relying on dating results, but also reviewing many known cases of long-distance dispersal, some of them that would be quite stupendous and difficult to believe, had they not been directly observed by humans within the last century or two. He raises the question – how can long-distance dispersal be said to be an unscientific explanation, when it is something that has been directly observed on many occasions? This puts the shoe decidedly on the other foot.

In the concluding chapter, de Queiroz notes that much of the appeal of vicariance was due to the imaginative vision it presented – flora and fauna riding on the continents, with a history that could be unraveled using plate tectonic reconstructions. de Queiroz quite deliberately puts forward an alternative imaginative vision, namely, that of the long-distance voyage, and the invasion and radiation of the rare heroic species that manage to cross oceans. He argues, effectively I think, that this set of stories is at least as capturing as the vicariance narrative, and that under this vision, we can see many cases where these rare events have played probably crucial roles in evolutionary history. Had one primate lineage never crossed the ancient Tethys sea, for instance, perhaps there never would have been great apes or, eventually, humans. This is Gould’s thesis in Wonderful Life retold in biogeographic form, and frankly, the fact that the relevant biogeographic events are much more recent than those of the Cambrian probably means that de Queiroz’s case for the role of contingency is stronger that Gould’s was.

de Queiroz’s focus on narrative makes for gripping reading. Under his pen, a topic that seems at first rather dry and academic becomes one that underlies everything you see when you’re on a hike or at a zoo, and you can also feel why there seems to be a impressive bit of emotion and rhetoric amongst the scientists involved in the vicariance debate. However, the focus on storytelling and reasoning from anecdote, while a noble tradition going back to Darwin and before, is itself a bit old-fashioned in this day and age. In modern evolutionary biology, we prefer that our conclusions are the result of formal statistical inference, rather than simply a narrative that we construct by gestalt based on accumulated experience. The cladistic methods in vicariance biogeography were actually an early attempt at this, which was part of their appeal. However, these methods had little in the way of uncertainty assessment, and the assumptions were such that the method could basically only give one answer: vicariance.

Much of vicariance biogeography was based on essentially repurposing standard cladistic programs for biogeographical uses, but with the construction of biogeography-specific programs, the situation began to change. Programs like DIVA (Dispersal-Vicariance Analysis; Ronquist 1997) and LAGRANGE (Likelihood Analysis of Geographic Range Evolution; Ree and Smith 2008) enabled researchers to input the phylogeny of a group, geographic range data, and obtain an estimate of the group’s geographic history as the product of a series of dispersal and vicariance events. DIVA was a parsimony method, but LAGRANGE was a probablistic method that explicitly took time into account, and it allowed researchers to have different geographies at different periods of time.

A Grain of Salt

These methods have enjoyed wide success. However, when I studied these methods for my Ph.D., one crucial thing I discovered was that each of these programs implemented the assumptions of the programmers, and that in the case of biogeography, the assumptions really matter. The core assumption made by both programs was that ranges could expand and contract along the branches of a phylogeny, but at speciation events on a phylogeny, all that could happen to a widespread range is that it break up (or, in the case of LAGRANGE, an additional option was subset sympatry, where a new species starts inside the range of the ancestor). One key event that these methods leave out is the possibility that dispersal and speciation are simultaneous events, i.e., founder-event speciation or jump dispersal . In founder-event speciation, a small subpopulation crosses a large barrier and instantly becomes genetically isolated, becoming a new lineage. While every proponent of vicariance biogeography accepts “dispersal” in the form of range expansion must happen at some point (this is, of course, required, since a species must become widespread before it can break up), jump dispersal was much more controversial.

Michael Heads, mentioned above, explicitly accepts range expansion but denies founder-event speciation through jump dispersal. Interestingly, Heads thinks that the DIVA and LAGRANGE programs are dispersalist programs that allow jump dispersal, but actually they do not. I believe he thinks this, because these programs are widely used by biogeographers who think of themselves as dispersalists or pluralists, but the actual assumptions about dispersal made by DIVA and LAGRANGE are actually quite similar to those made by Heads (Matzke 2013). In short, while many biogeographers would not trust Heads’s book any further than Alan de Queiroz could throw it, they are in effect adopting similar assumptions when they make use of programs that hard-code assumptions about biogeographical process that trace straight back to the vicariance biogeography school!

In an attempt to remedy this situation, I wrote my own program, the R package “BioGeoBEARS”, that allows users to turn on, or turn off, the different biogeographical processes, and see what the effect is on the statistical likelihood of the data. In cases where researchers don’t feel that they know ahead of time the relative probability of different processes, the weight of each process can be set as a free parameter. The program then varies the values of these parameters, and picks the set of parameter values that confers the maximum likelihood on the data. The likelihoods of the geographical data under different models can then be compared using standard methods in statistical model choice, such as the likelihood ratio test and Akaike Information Criterion.

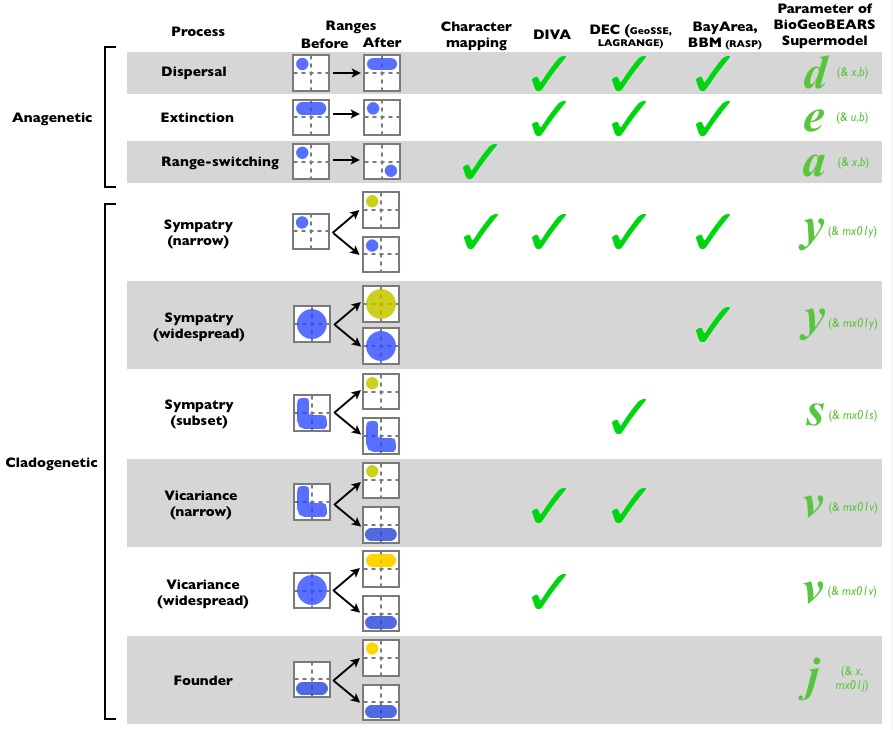

Caption for Figure 1, Matzke 2013, Frontiers of Biogeography: The processes assumed by different historical biogeography methods. Each of these processes is controlled by the specified parameter(s) in the BioGeoBEARS supermodel, allowing them to be turned on or off, or estimated from the data. Note that whether or not the data support a particular free parameter is an empirical question that should be tested with model choice procedures. Note also that this graphic deals only with the range-changing processes assumed by the different methods. BioGeoBEARS does not attempt to replicate e.g. the parsimony aspect of DIVA, just the processes allowed by DIVA (the BioGeoBEARS “DIVA” model can be called “DIVALIKE” to emphasize that it is a likelihood implementation of the processes assumed by DIVA). Similarly, BioGeoBEARS does not yet implement the “SSE” (state-based speciation and extinction rates) features of the GeoSSE model (Goldberg et al. 2011) of diversity. The ClaSSE model (Goldberg & Igić, 2012) can in theory use a parameter to represent the probability of each possible combination of ancestor range, left descendant range, and right descendant range. In that sense ClaSSE is the ultimate supermodel, although users would have to develop their own parameterizations to produce a reasonable biogeographic model, and the number of parameters inflates dramatically with number of areas – on defaults, 9 areas means 2^9-1=511 possible ranges, and this means 511x511x511 = 133,432,831 possible combinations of ancestor/left descendant/right descendant. The cladoRcpp R package, a dependency of BioGeoBEARS, is designed to efficiently calculate probabilities for these combinations, under the implemented biogeography models.

de Queiroz would be pleased to know that, in 25 example clades that I selected to test the different models, models that included founder-event speciation as a process outperformed the traditional models in almost every case. The results were often dramatic: in many cases, models including founder-event speciation had model weights hundreds of thousands or millions of times higher than the traditional models. Furthermore, simulations show that accuracy and precision of estimated ancestral ranges increases dramatically when better-performing models are used. I have a found a few cases where the traditional models “won” – Taygetis clade butterflies in South America are one, probably because they are a continental clade where many species have widespread, overlapping ranges. But the overall picture is clear: founder-event speciation is a crucial process in many clades, and we ignore it at our peril.

This is why I said above that the dispersal-versus-vicariance debate should not be shrugged off with answers like “the right answer is both.” First, there are different sorts of dispersal, and accounting for one does not mean that you have accounted for all of them. Second, what we really want is not just a list of valid and invalid processes. What we really want to do in science is to measure the relative importance of each process. BioGeoBEARS is the first attempt to do this, although of course it is quite likely that even more sophisticated improved models will be invented in the future.

I am, of course, tooting my own horn here, but who can blame me? A popular book on my favorite topic, historical biogeography, confirms the statistical conclusions I reached in my Ph.D. research, although on totally separate grounds. I suspect this is rare amongst Ph.D. theses. So, take my assessment of The Monkey’s Voyage with that grain of salt. However, I believe that my conclusions about de Queiroz’s readability, grasp of the history and personalities involved, and his expertise on the relevant science are accurate, whatever the detailed fate of my own research. Certainly, reading de Queiroz’s book is a far more enjoyable way to find out what is going on in historical biogeography than reading a recent Ph.D. on statistical model choice!

References

de Queiroz, Alan (2014). The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped the History of Life. Basic Books: New York, pp. 1-348. http://themonkeysvoyage.com/ – Amazon Link

Heads, Michael J. (2012) Molecular Panbiogeography of the Tropics. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Matzke, Nicholas J. (2013). BioGeoBEARS: BioGeography with Bayesian (and Likelihood) Evolutionary Analysis in R Scripts. R package, version 0.2.1, published July 27, 2013 at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=BioGeoBEARS. PhyloWiki page: http://phylo.wikidot.com/biogeobears

Matzke, Nicholas J. (2013). Thesis abstract: Probabilistic historical biogeography: new models for founder-event speciation, imperfect detection, and fossils allow improved accuracy and model-testing. Frontiers of Biogeography, 5(4), 242-248. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/44j7n141

Matzke, Nicholas J. (2013). “Formal Model Testing of the Dispersal-Extinction-Cladogenesis (DEC) Model Reveals that Founder-event Speciation is a Dominant Process Structuring the Biogeography of Island Clades.” Systematic Biology, in review.

Matzke, Nicholas Joseph (2013). Probabilistic Historical Biogeography: New Models for Founder-Event Speciation, Imperfect Detection, and Fossils Allow Improved Accuracy and Model-Testing. Ph.D. thesis, Department Integrative Biology and Designated Emphasis in Computational and Genomic Biology, University of California, Berkeley. Pages 1-240. August 2013. Available at: http://phylo.wikidot.com/local–files/biogeobears/Matzke_PhD_FINAL_v5_w_refs.pdf

Ree, R.H. & Smith, S.A. (2008) Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Systematic Biology, 57, 4-14.

Ronquist, F. (1997) Dispersal‐Vicariance Analysis: A new approach to the quantification of historical biogeography. Systematic Biology, 46, 195-203.