Understanding creationism, III:

An insider's guide by a former young-Earth creationist

By David MacMillan.

3. You don’t evolve, your species does.

Creationists often conceptualize evolution as something which is purely vertical: successive changes from parent to child to grandchild to great-grandchild accumulating over time. They can hardly be faulted for this misconception, because this view seems to be shared by the general public and even reinforced by the sometimes-imprecise explanations and depictions of evolution by museums and science educators.

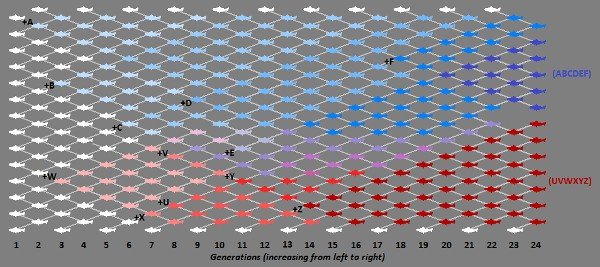

Evolutionary adaptation, however, does not happen in a straight line from parent to child. Rather, adaptation takes place throughout a population as different genetic sequences spread outward from parents to all their offspring and are recombined and reshuffled in many different individuals each successive generation. Evolution is wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff. It is the combination of changing genetic material across an entire population that makes major evolutionary adaptation possible; without this constant mixing and recombination from the entire population, evolution would grind almost to a halt. Evolution is a phenomenon that functions not at the level of the individual, nor at the level of individual lineages, but across the entire population within the species (Figure 1).

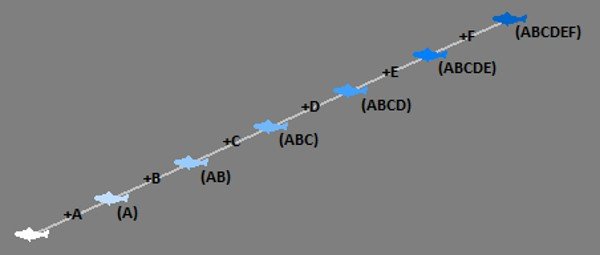

Unfortunately, depictions of evolution often show individual specimens arranged linearly in ascending order: apes to humans, theropods to birds, and the like (Figure 2). Such representations make it easy to miss the population aspect. Even an accurately depicted branching tree of evolution can still be misunderstood to represent individuals rather than whole populations.

Biologist PZ Myers explains it very well in a recent blog post:

Evolution isn't sequential. It's massively parallel. Massively. Humans have about 20,000 genes, and all of them are evolving at once, with trial runs in about 7 billion individuals. New variants are arising all the time, and then they're tested to destruction in multiple combinations over time. Scrap your weird idea that the pieces of a complex system must be developed one at a time – they can't, and all of them are being constantly tinkered with. It is the most badly designed scientific experiment or engineering program ever, with no controls and every variable getting randomly tweaked at random intervals. So don't be surprised that multiple elements are getting juggled.

Understanding and addressing the misconception (Figure 2) is vital because it determines how plausible common descent seems (as well as how plausible objections to evolution will seem). In a game of cards, it would be incredibly rare to draw four aces on the first try. But if you have hundreds of card players all trading cards back and forth between their hands, it’s virtually certain that someone in the group will end up with four aces almost right away.

Even when creationists with professional scientific training understand that evolution is supposed to happen at the population level, they will still (wittingly or unwittingly) reinforce this misconception because it fits better with their philosophical presuppositions. This approach is seen particularly in statistical or probabilistic arguments, especially among intelligent-design creationists. Demonstrating the difference between the misconception of “individual” evolution and the reality of “population” evolution quickly displays the fallacy in this sort of reasoning.

For example, a creationist may calculate that the probability of a fish arriving at a particular DNA sequence by chance mutation is some astronomical number like 1 in 10 30. This number, he believes, is far beyond the limits of what he thinks is reasonable. 1 Now, his estimate is probably suspect, but that’s beside the point, because evolution doesn’t happen in just one fish; it happens in a population of fish. A school of fish like sardines may contain 100 billion individuals, each with around 25 chromosome pairs. During meiosis, each maternal and each paternal chromosome can undergo a simple crossing-over recombination two or three or even more times. A single breeding pair of sardines can produce 20,000 eggs in one clutch. And this is just one school; there may be multiple schools of the same species.

If we suppose five separate schools, there is the potential for 1.4 million trillion trillion (2.1 x 10 30) newly recombined genotypes 2 for this species in a single breeding season. Now, this is just a very generalized example; using different numbers would of course generate different results, and a rigorous examination of this question would require analysis of mutation rates and much more. But my rough example illustrates how seemingly astronomical odds can turn out to be much less challenging once a shift is made from thinking in terms of individual evolution to thinking in terms of population evolution.

For individuals who are not interested in learning about the underlying microbiology, the card game example from earlier is probably sufficient: the chance of one lone individual drawing one exact hand off the top of the deck is very low; the chance of somebody getting the desired hand when there are hundreds (or thousands) of players all constantly exchanging cards is very high.

Easy-to-understand examples are vitally important. At heart, these sorts of probabilistic arguments usually advanced by intelligent-design creationists are nothing more than arguments from incredulity: “I can’t imagine how it’s possible, so it must not be.” Although this is an obvious logical fallacy, it doesn’t usually do any good to point it out – “just because you can’t imagine it doesn’t mean someone else can’t” – because creationists will merely assume such imaginings are only wishful thinking by atheist evolutionists determined to defend a theory that would otherwise fall apart. That’s why it’s vital to have straightforward examples to demonstrate the fallacies inherent in the creationist understandings.

Footnotes.

-

Some of the smallest protein-coding genes are around 22 codons in length, or 66 nucleotide base pairs; the chance of arriving at a specific 22-codon sequence by pure chance is roughly 1 in 10 30. Note, however, that the size of the genome plays a major role here. Even as few as 4-5 different species with genomes roughly the size of our own are likely to have matching sequences of this length in their junk DNA, simply by statistical accident. Also keep in mind that creationists often wrongly assume a gene must be complete and fully functional before natural selection can begin selecting for it and developing it further, but they are wrong. Selection doesn’t require the emergence of some new major advantage; selection requires only a functional difference. Even a change in a single codon can alter a protein enough to cause a division to form between the original genotype and the altered genotype. For example, a small mutation that alters the start of the breeding season by even a couple of days can cause a population to divide into two overlapping groups which will continue to evolve both separately and in concert.

-

In ordinary sexual reproduction, each parent contributes half its genetic material by selecting one chromosome from each of its chromosome pairs to donate. Each of the offspring’s chromosomes is thus an exact match to an individual chromosome in one of the parents. A crossing-over recombination takes place when pieces of both chromosomes in a given parental pair are spliced together to produce a new donated chromosome. Not only does crossing-over result in a newly arranged package of genes to be passed on to the next generation, but it also creates an entirely new genetic sequence at each splice point. This event is not technically a mutation in the same way as substitution, insertion, deletion, and transposition, but it still generates new genetic information. Fortunately, crossing-over recombinations rarely interfere with any existing functions, simply because it is very unlikely for any given splice point to intersect a functioning protein sequence. When a recombined chromosome is combined with the chromosome from the other parent, the result is a new, complete genotype which is both heritable and selectable.