Update on the Tree of Birds

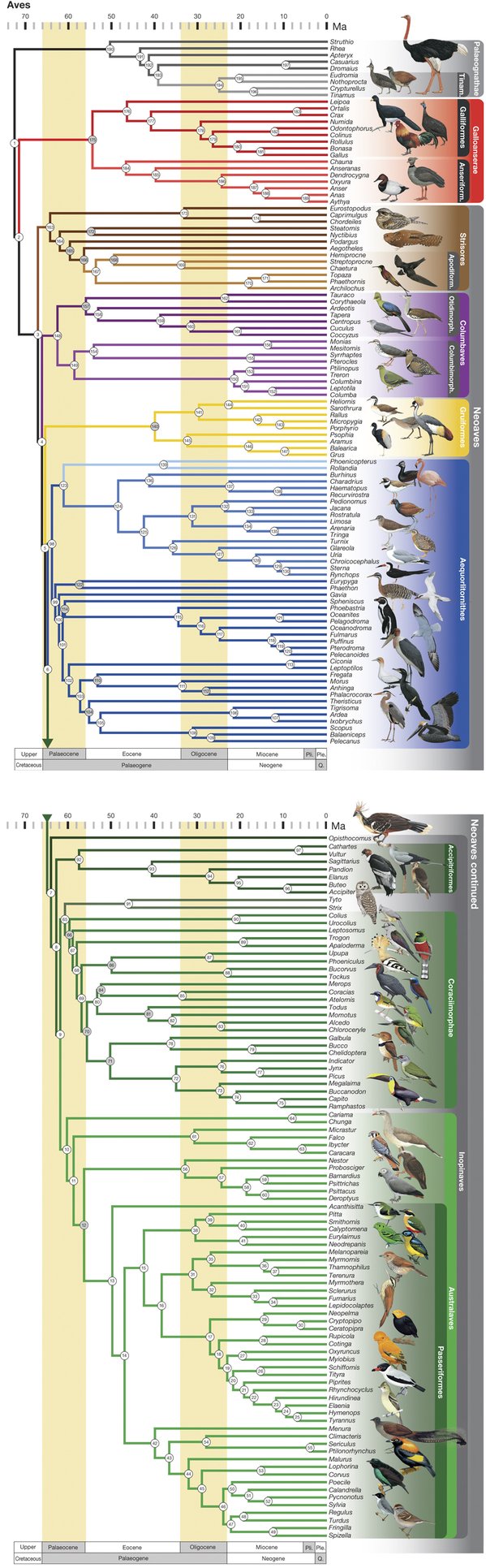

The tree of birds just got a bit more accurate with a study published last October. We first covered the ever-evolving tree in 2014, when we posted about a study in Science magazine that used phylogenomics and thousands of genes sequenced from 48 bird species to produce what was thought to be the most accurate phylogenetic tree of birds to date (Jarvis et. al., 2014; see their tree here). Since then, a different team of scientists published a new phylogeny of birds that it claims is the most comprehensive (Prum et. al., 2015; see their tree below). So what is the difference between these two trees and how they were constructed, and which is more accurate?

The biggest difference between the methods of the two studies is the amount of data used. In the Jarvis et. al. study, the authors sequenced the whole genomes of 48 bird species and aligned thousands of genes. But Prum et. al. criticize this methodology as too “sparse” of a sampling; instead, they used 198 bird species and two crocodile species. Because sequencing that many whole genomes would be costly and time-consuming, Prum et. al. developed genetic markers that targeted highly conserved “anchor” regions of vertebrate genomes – regions did not change much over many years. Using this technology, the new tree of birds could be developed with only about 400 genetic regions instead of the thousands of genes in the previous study.

If there is a tradeoff between analyzing more genes or more species, is it more accurate to compare fewer genes between more species, or more genes between fewer species? One is not inherently better than the other, but rather, the way in which each is used relative to common issues in constructing a phylogenetic tree determines accuracy of the tree.

One such issue is distinguishing important genetic signals from noise. Genomic data contains a certain amount of “phylogenetic signal,” the informative genes that determine lineage. This signal must be differentiated from non-phylogenetic signal–genes that falsely suggest certain relationships. For example, non-phylogenetic signal can arise because species divergence events that happened close together in time are difficult to distinguish, or when species that diverged from a common ancestor a long time ago independently develop similar traits (called homoplasy). A 2011 article in PLOS Biology analyzed published phylogenetic trees and noted that merely adding more genes did not improve their accuracy because adding genes amplifies all signal (non-phylogenetic and phylogenetic alike).

Additionally, a phylogeny will only be accurate if the orthologous genes–those genes shared between species that were inherited from a common ancestor–are correctly identified. And that depends on the ability of software to distinguish orthologous genes from similar genetic sequences between species that code for genes that are not orthologous but rather are xenologous (transferred via horizontal gene transfer instead of inherited from the common ancestor) or paralogous (resulting from duplication of a gene). (Read more about orthologous, xenologous, and paralogous genes here.)

The model of evolution that researchers choose to use in their analysis can also greatly influence phylogeny accuracy. The PLOS article authors analyzed models and found some have difficulty detecting nucleotide substitutions, resulting in trees that are dominated by non-phylogenetic signal.

While analyzing a larger set of species won’t help when a model of evolution is inadequate or software has issues identifying orthologous genes, it can help with the issue of non-phylogenetic signal. Increasing the number of species in a study generally increases the phylogenetic signal-to-noise ratio, making it easier to detect substitutions that can lead to homoplasy, and also can improve accuracy by breaking up long branches. But the PLOS article states that it is not enough to just add more species; researchers should analyze more species that evolve slowly and comprise outgroups closely related to the group of interest.

Thus, including more species to construct a phylogenetic tree may be beneficial for tree accuracy, but only as long as methods for determining orthologous structures and modeling evolution are sufficient, and the chosen species are appropriate. Because Prum et. al. looked at more species while keeping these important factors in mind, and developed quality genetic markers that analyze enough genetic regions to determine phylogenetic relationships, they argue their tree is the most accurate yet. It is a convincing argument for the moment, but phylogenetic analysis can always be improved with better software and models, and the tree of birds (and the tree of life in general) will be constantly revised in the future as these methods improve.

The latest tree of birds presents a few differences from the Jarvis et. al. tree, some of which Prum et. al. suggest resulted from their larger sample size. One of the most striking differences is in the classification of the major bird groups. Jarvis et. al. propose that the initial divergence of a highly debated branch of birds, called Neoaves, resulted in two main groups: Columbea, containing birds like doves and flamingoes, and Passerea, containing a wide variety of species (parrots, falcons, penguins, and eagles, to name a few). But Prum et. al.’s tree instead splits Neoaves into five groups: Strisores (nightjars, hummingbirds, and frogmouths), Columbaves (cuckoos, pigeons, and sandgrouse), Gruiformes (cranes, coots, and rails), Aequorlitornithes (grebes, flamingoes, and shorebirds), and finally the very diverse Inopinaves (owls, vultures, and parrots). Also, Jarvis et. al. place pigeons, mesites, and sandgrouse in their own branch (Columbea) apart from the rest of Neoaves, while Prum et. al. rejected that for their five-group system. The Prum et. al. classification of Neoaves is likely the most accurate because they included more species that diverged close to speciation events (called nodes), which is especially important when the time between multiple nodes is short.

These findings bring up some new ideas about bird evolution and also support some old ones. For one, the new tree of birds developed by Prum et.al. supports a previous theory that swifts and hummingbirds, neither of which is nocturnal, evolved from a group of birds that had been nocturnal for 10 million years (Jarvis et. al. finds a similar relationship). Also, the new finding of the group consisting of waterbirds and shorebirds (Aequorlithornithes) suggests that the divergence of birds into different environments occurred with some level of restriction, known as evolutionary constraint. But as interesting and exciting as the new tree and its implications for bird evolution are, it is unlikely to be the final word on bird evolution. Other studies have also been published examining parts of the bird tree (like Rocha et. al. on the bird genus containing woodcreepers and Bell et. al. on an extinct group of Cretaceous birds). A new, more accurate complete tree of birds that supports or rejects these theories may be only another year away. Such is the nature of scientific research.

This series is supported by NSF Grant #DBI-1356548 to RA Cartwright.