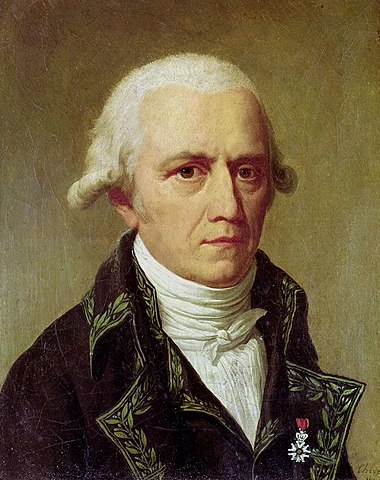

A belated happy birthday to Lamarck

Since 2009 I have posted every year a happy birthday greeting to the first evolutionary biologist, the Chevalier de Lamarck. Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck, was born on 1 August 1744, so now more than 276 years ago. In my opinion he was the first true evolutionary biologist – he argued for common ancestry of animals, and he actually had a proposed mechanism that biased change in the direction of adaptation of a species to its environment. He was wrong about the mechanism, but right about the need for one. He was also a great figure in invertebrate systematics, in which he made great strides.

Well, I’ve said all that before, and in addition this year the birthday notice is late. No apologies for that, the Pandas Thumb Crew spent his birthday desperately struggling to bring PT back up after a hardware failure of its server. We’ve talked about many aspects of his life, good and bad. Is there anything important spo far left unsaid?

Actually yes. That he invoked an inherent complexifying force, and that it was quietly abandoned by Lamarckians in subsequent decades. An interesting story.

People today think of Lamarck as a crackpot, which he was not. They think of him as the great inventor and advocate of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Whenever someone suggest that a phenotypic modification of a species could be inherited, everyone succumbs to the temptation of calling it “Lamarckian”. Actually they’re wrong on both scores. Lamarck was by no means the first to suggest that acquired characteristics are inherited – it’s an idea that goes back at least to the ancient Greeks, and most likely far beyond them. No one in Lamarck’s time would be surprised by Lamarck’s use of the phenomenon – they all always knew it was true. So they would not think of him as having done anything of interest by using it.

Actually, the modifications Lamarck was talking about were not the direct effects of environment, but effects of use and disuse. When we use our muscles they tend to get bigger. To Lamarck, it was that use that had the effect in modifying the legacy passed on the next generation. A bird tried to fly faster, so its offspring’s wings were bigger.

But there’s another phenomenon in Lamarck’s theory, one that most people don’t know of. This is that in addition to the effects of use and disuse, there a whole other force at work in Lamarck’s theory. And that is the inherent complexifying force.

Here, for example, is a summary by Lamarck contrasting the existing theory with his own:

Conclusion adopted hitherto: Nature (or her Author) in creating animals, foresaw all the possible kinds of environment in which they would have to live, and endowed each species with a fixed organisation and with a definite and invariable shape, which compel each species to live in the places and climates where we actually find them, and there to maintain the habits which we know in them.

My individual conclusion: Nature has produced all the species of animals in succession, beginning with the most imperfect or simplest, and ending her work with the most perfect, so as to create a gradually increasing complexity in their organisation; these animals have spread at large throughout all the habitable regions of the globe, and every species has derived from its environment the habits that we find in it and the structural modifications which observation shows us.

Note the production of animals “in succession” from simplest to most perfect in a scale of “gradually increasing complexity”. Although Lamarck drew one of the very first phylogenies, his thought was also dominated by a Great Chain of Being from simplest to most complex. In fact, he believed that animal species climbed this scale continually, and if one became extinct, this was temporary, because it would arise again from animals further down on the scale of perfection.

Why do we not hear of this? I think that it is simply that, as the 19th century wore on, with dramatic developments in physics and chemistry, an inherent complexifying force seemed more and more unlikely, In the aftermath of Darwin’s work, Lamarckian views were still around and advocated by his intellectual descendants. But the more mystical aspects of the theory were quietly dropped. Scientists no longer wanted to consider an inherent complexifying force, or even effects of use and disuse. The former was dropped, the latter became the direct effects of the environment on the organism.

Today any effect of environment on the organism, such as epigenetic modifications, is called “Lamarckian”, usually quite inaccurately. There is not going to be a true revival of Lamarckian views, as they would involve mystical trends towards complexity, and effects of will power on inheritance. Neither has much appeal on light of modern physics. Nevertheless, Happy Birthday to Jean-Baptiste, the first true evolutionary biologist.