The mystery of phosphine gas on Venus

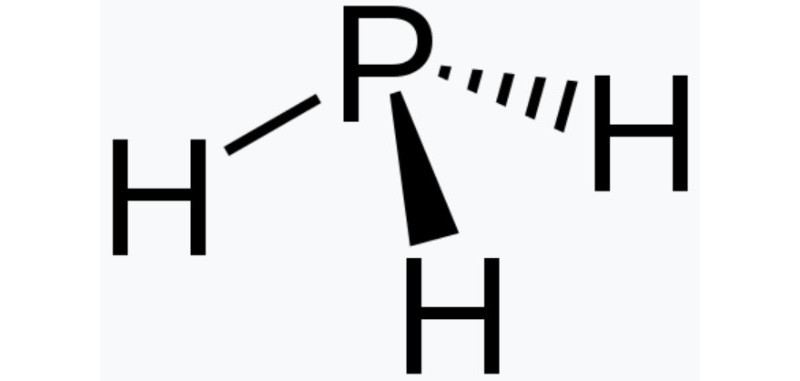

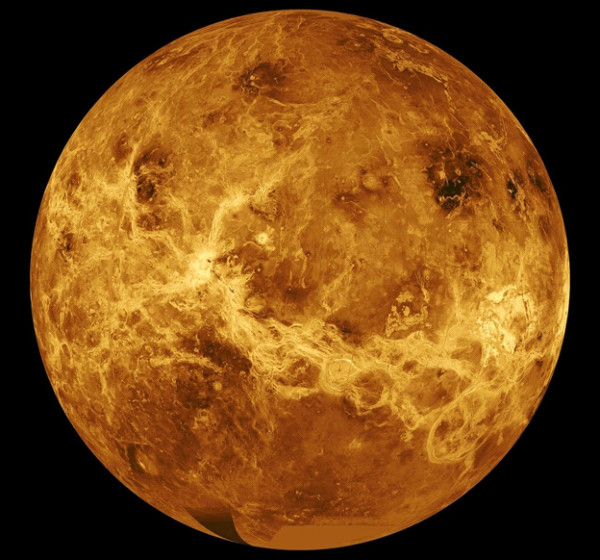

Is there life on Venus? Yesterday, September 14, 2020, an article in Nature Astronomy reported careful measurements consistent with trace amounts of phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus. There is no known geochemical process that can produce phosphine. This phosphine might have come from life. Life on Venus, if this is what we found, might be microbes floating in the clouds.

Time will tell, but this may become a landmark publication.

The clouds of Venus are temperate, but full of sulfuric acid. Scientists wondered for decades whether or not the clouds could sustain life. We find microbes on Earth in extremely hostile environments. While no human could live unprotected on Venus, maybe a microbe could. Now, with this new finding, we are all wondering if maybe, in fact, there is life on Venus.

There has been an explosion of media coverage in just the last day. Today’s XKCD gives us a great filter by which to judge coverage:

Not Cautious Enough: They found life on Venus!

Appropriately Cautious: These molecules might be produced by life, or by weird high-heat chemistry.

Too Cautious: There is growing evidence that the atmosphere of Venus contains molecules.

One of the study’s authors, Paul B. Rimmer, answered some questions for us at Peaceful Science, and I look forward to seeing that conversation unfold more. Asked what this means for the origins conversation:

Not at all, at present. There’s too much we just don’t know. The first step is to make sure the molecule we see is phosphine and not some unknown molecule that is producing the feature, how much there really is, how it’s distributed through the clouds, and what implications that has for where to look for its source.

We then need to find out if there’s actually life in the clouds of Venus.

Even when that’s done, there’s still a real possibility that life from Earth hitched a ride to Venus early on, so this may not imply more than one origin.

If on Venus, Enceladus, Mars, Europa, any life is found that has a separate origin from life on Earth, that has enormous implications for origins of life and the prevalence of life in the universe. It suggests it’s not all that hard to make life from non-life after all. This is why exoplanets are so compelling. Unless you appeal to panspermia, finding life in another stellar system, close enough for us to see evidence of it, strongly implies that origin of life is relatively easy.

Asked, what media coverage is most likely to neglect, he responded,

Two things come to mind:

(1) The uncertainty inherent in science. So far, no known explanation except for life can account for the detection, but we don’t know a lot. A lot more investigation needs to be done, especially involving abiotic phosphorus chemistry in sulfuric acid droplets. There’s also huge problems (that you will know more about) with life thriving in 90% sulfuric acid.

(2) That lots of people since Carl Sagan have thought about life in the clouds of Venus and have worked on this question way before our group started looking into this detection and its possible implications. I’d especially highlight David Grinspoon’s research into possible life on Venus.

What was most exciting about this paper?

The detection of phosphine itself. Whatever its cause, by all rights it just shouldn’t be there, and the mystery is compelling.

This is a grand mystery, and that is exciting. The fact that we don’t know what gave rise to this phosphine what makes this finding so compelling.

Was the phosphine, in the end, produced by something other than life? Is there any combination of geological and chemical processes, perhaps with input from meteorites, that could produce phosphine on an ongoing basis?

Or is this really life? Did that life first arise when Venus had oceans, and then move to the skies? Was life seeded in Venus by probes in the 1970s and 80s sent from Earth? How much like or unlike life on earth will these microbes be?

Or was it the most mundane of all options? Could there be an error in the detection? Is there another chemical that absorbs light at the same wavelength? Was there some other technical loophole that misleads us here?

Questions like these are surely going to shape research going forward. Perhaps we have put too much focus on Mars, to the exclusion of exploring other worlds. What will a mission to Venus tell us about these questions? Would it be possible to return samples of those sulfuric clouds to Earth?

This is the great mystery that this paper offers. That is what makes it compelling. It is the questions of phosphine gas on Venus that draw us in.

Joshua Swamidass, a new member of the PT Crew, is Associate Professor, Laboratory and Genomic Medicine, Washington University in St Louis. He is the author of The Genealogical Adam and Eve and the founding scientist of the blog Peaceful Science.