Protein chimeras are evidence against ID claims!

Where do novel functional proteins come from? It has become something of a staple of the ID-creationism movement that proteins with novel functions and structures are practically impossible to evolve.

Why? In part because functional protein sequences, that is, protein sequences with functions that are useful to living organisms (such as protecting DNA from damage or promoting essential chemical reactions), are supposedly hyper-astronomically rare among all possible protein sequences. So rare, ID-creationists argue, that even with unrealistically huge population sizes and rates of mutation, not a single functional protein sequence could be expected to evolve in the entire history of the universe.

The intended message is, of course, that since we know of millions of functional protein sequences within the diversity of life on Earth, and since supposedly none of them could have evolved, Intelligent Design becomes the only other plausible explanation for why they exist. And so, you know, evolution must be false and there must be an Intelligent Designer.

One of the main champions of this claim is ID-creationist and researcher Douglas Axe, who is one among few ID-creationists with actual qualifications in biochemistry. Back in 2004 he published a paper in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution detailing some experiments he did on a protein enzyme 150 amino acids in length. In this paper he concludes that functional protein enzyme sequences of a similar size (150 amino acids) are so rare among all possible proteins, that they are found at the astonishingly low frequency of approximately 1 in 1077. This number is frequently cited in the ID literature, ranging from Stephen Meyer’s book Darwin’s Doubt, through being bandied about on the Discovery Institute’s pro-ID blog Evolution News & Science Today, to the recent pro-ID paper published in the Journal of Theoretical Biology.

Now 1 in 1077 is certainly a very low frequency, and all the way back in January of 2007, Panda’s Thumb contributor Arthur Hunt wrote a post detailing good reasons why Axe’s work is incapable of supporting this 10-77 frequency. And while I will not reiterate those reasons here, in a future post I intend to revisit some of the conclusions ID-creationists draw from Axe’s work.

Rather, given that Axe’s work is once again being cited and is doing the rounds in ID-creationist circles, I thought this would be as good a time as any to visit some work in experimental molecular biology that massively contradicts Axe’s number. And to not beat around the bush too much, we’re talking a 72 order-of-magnitude discrepancy between Axe’s frequency of 1 in 1077 and what other experiments in probing protein sequence space reveal.

I will give an account of experiments done to probe a particular process of novel protein evolution, called gene fusion, which turned out to be able to find functional proteins at a rate of 1 in 3.3×105. To put the magnitude of the discrepancy into context, it’s 1 followed by 72 zeroes, which is a number that seems to fit in the arena concerning things like the number of atoms in the observable universe (estimated at ~1080). Quite a margin of error!

The question of how novel protein-coding genes have arisen by evolutionary processes throughout life’s history has many possible answers, ranging from processes such as mutational divergence of duplicate genes, through emergence by frameshift mutation, to proteins evolving de novo from non-coding DNA.

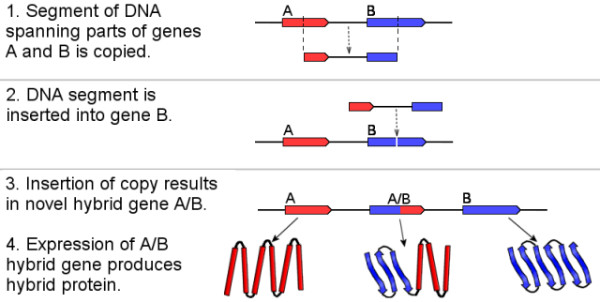

Another idea is that novel protein-coding genes can arise by recombination of smaller fragments of already existing genes, resulting in chimeric sequences with the potential for new functions. An example of how such a chimeric gene can arise is depicted in Figure 1.

Put very succinctly, take two (or more) pieces of already existing genes and combine them into a new gene which is a hybrid of the two. Since for the purposes of this post I am defining a gene as a piece of DNA that encodes a protein, the resulting hybrid protein consists of fragments of other existing proteins, and potentially has novel and useful biological functions, possibly facilitated by folding into a novel 3-dimensional structure.

I’ve come across an interesting PhD thesis, Exploring the protein universe: a study of subdomain driven evolution, by Gabriel Rawcliffe, detailing experiments to explore the evolution of novel functional proteins, by a version of this process of combining pieces of different genes, which the author calls “subdomain driven evolution.”

Rawcliffe sought to determine whether this process of generating hybrid genes by combining pieces of existing genes was capable of finding novel functional proteins. To do so, Rawcliffe performed his experiments using 107 different genetically engineered auxotrophic strains of E. coli bacteria. Each strain had only one of 107 different genes rendered nonfunctional.

To get some terminology down, an auxotrophic organism is a mutant variant of the same species that has lost the ability to biosynthesize a key organic compound that is essential for growth. Think of how we as humans have lost the ability to synthesize our own vitamin C, due to the pseudogenization (mutations have rendered a gene nonfunctional, turning into a so-called pseudogene) of a key gene in the vitamin C biosynthesis pathway. This means we need vitamin C in our diet to survive since we can’t make it within our own bodies. The particular gene that has mutated and become nonfunctional is found in humans and many of our close primate cousins and is known as GULOP (we inherited this nonfunctional gene from a distant primate common ancestor).

A similar principle goes for the E. coli bacteria used in Rawcliffe’s experiments. He used 107 different auxotrophic strains, that is, 107 variants of E. coli, each of which carried a single genetically engineered mutation that made that strain unable to biosynthesize one of 107 different organic compounds the bacteria need to grow and divide.

This compound could be anything from a particular sugar or amino acid, to lipids used in the cell membrane, or other essential constituents of E. coli. Experiments of this nature are also known as “knock-out” experiments, denoting that the experiment is performed with an organism carrying a gene that has been “knocked out” of function.

Rawcliffe’s strategy was then to find out whether it was possible to find a novel hybrid gene that was capable of performing a function that compensated for any one of the 107 different knocked out genes.

He went on to screen a library of 1.65 million different hybrid genes created (using a molecular biology protocol called ITCHY) from what was essentially random fragments of existing genes, to see whether one of these millions of new hybrid genes could perform a function that could compensate for one of the 107 different dysfunctional mutant genes. It’s important to note here that the novel hybrid gene might not perform the same function as the gene that was knocked out, but it is still able to rescue the strain by performing some other compensating function.

The protocol he employed to detect whether such a function existed among his millions of random chimeric genes is depicted in this Figure 2.

To elaborate a bit, what Rawcliffe does is first and foremost to use some rather technical molecular biology methods (the ITCHY protocol) to generate a huge library of random gene hybrids. Due to various technical limitations, his hybrid genes are restricted to consist of only two fragments at most, each derived from a different gene (essentially similar to that A/B hybrid depicted in Figure 1).

Rawcliffe generated a library of ~1.65 million different such hybrid genes that met the specifications for his experimental protocol. Rawcliffe then went on to use this library of ~1.65 million hybrid genes in a process called bacterial transformation, which basically means he gets his 107 different auxotrophic strains of E. coli to transport the DNA encoding the novel hybrid genes inside themselves.

Once the DNA is inside the bacterial cells, these same bacteria can now “read and decode” the DNA and thereby produce the novel hybrid gene. And here comes the crucial part: if by chance this novel hybrid gene can perform a function that compensates for the “knocked out” gene, the bacteria will be able to grow in a Petri dish on agar that otherwise lacks the essential nutrient. If any of Rawcliffe’s auxotrophic strains can grow and form a colony on a Petri dish, it is known as a rescue clone (because the inserted DNA “rescued” its ability to grow despite having a gene knocked out).

Of course, having a negative control is important if we are to conclude that the bacteria grow because they received a novel hybrid gene (instead of gaining this ability through some other spontaneous mutation, or perhaps having his culture cross-contaminated with bacteria that do not carry “knock out” mutations), so, crucially, Rawcliffe also tested his auxotrophic bacteria without giving them any of the DNA containing novel hybrid genes.

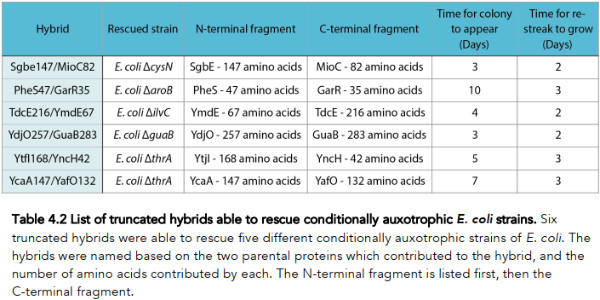

Okay, so what did Rawcliffe find? He has this table summarizing his findings.

Basically what Rawcliffe found was that among his ~1.65 million hybrids, there were six different genes capable of performing a function that rescued one of his 107 auxotrophic strains (listed under the Hybrid column). Reading the table we see, for example, the hybrid gene Sgbe147/MioC82, being derived from a fusion of fragments from the genes Sgbe147 and MioC82, rescued a strain of E. coli having the gene cysN knocked out.

Rawcliffe goes into more detail in his thesis, analyzing the particular strains that were rescued, what function was initially knocked out, and from which genes the fragments that constitute the rescuing hybrid gene was derived. One of his six rescue clones turned out to be a case of “self-rescue,” which means that a piece of the gene that was originally knocked out was also found as part of the hybrid gene that performed the rescue function.

Interestingly the self-rescue is not a fully intact version of the original knocked out gene, being partially constituted of a smaller fragment from it, but is nevertheless able to carry out its function, at least while fused to a fragment of another gene. Rawcliffe writes,

4.3.2.4 Rescue of E. coli ΔguaB The rescue of E. coli ΔguaB represents a partial self-rescue; it was rescued by the hybrid YdjO257/GuaB283, a combination of 257 amino acids of YdjO and 283 amino acids of GuaB. The full length GuaB is 488 amino acids, meaning that ~60% of GuaB, fused to an almost full length YdjO (267 amino acids), seemingly performed the function of GuaB.

For the purposes of this post we can discount a partial self-rescue. What we need to know here is only that among Rawcliffe’s original ~1.65 million hybrid genes, there were 5 novel ones capable of performing a function essential for life in a real living organism.

That means we now have a number to compare to the number that gets bandied about in the ID-creationist literature, that functional proteins are found at the hyper astronomically low frequency of about 1 in 1077. The number we have is ~1.65 million divided by 5 = ~330 000. So we have a frequency of functional proteins of 1 in 330 thousand.

Rawcliffe didn’t have to search through 1077 random combinations to find a new functional protein, and apparently truncated fragments of already existing protein sequences, when fused together, were capable of performing other functions. Thus, Axe’s estimate is in error, as noted above, by something on the order of 72 orders of magnitude.

References:

Axe DD. Estimating the prevalence of protein sequences adopting functional enzyme folds. J Mol Biol. 2004;341(5):1295-1315. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.058

Rawcliffe, G. (2019). Exploring the protein universe: a study of subdomain driven evolution (Thesis, Doctor of Philosophy). University of Otago. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10523/9772