Flagellum research on the front burner again

We have not discussed the bacterial flagellum on PT in a good long time – one of the last instances was Nick Matzke’s 2007 article, The Edge of Creationism, a clever pun on Michael Behe’s book title, The Edge of Evolution. In that article, Dr. Matzke thoroughly debunks Dr. Behe’s contention that the flagellum could not have evolved, hence was designed.

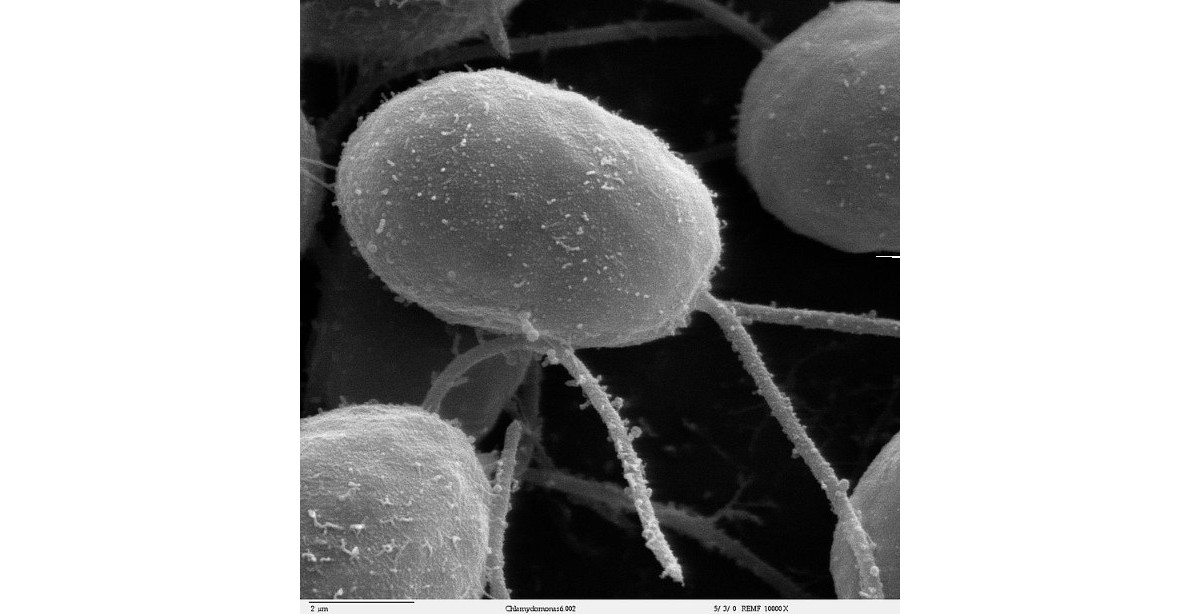

Dr. Matzke, I am pleased to note, is at it again. He is a part of an international team led by Matthew Baker to, in their words, discover “How life got moving: reconstructing and re-evolving the bacterial flagellar motor, piece-by-piece.” Their intention, according to a press release from the University of New South Wales, is “to estimate what an ancient flagellar motor – the tiny rotating wheel that powers the swimming movement of bacteria – might have looked like, and then re-engineer it for further experimentation and research.” So much for not evolving.

In what must be an improbable case of convergent evolution, a team headed by Morgan Beeby at Imperial College London has been awarded a grant for a project titled “Darwin rwinDa: rewinding and rerunning evolution to study innovation in action” (no, that is not a typo). According to a press release from Imperial College, their intention is to discover “How can gradual, Darwinian evolution build such a structure if not by inventing all necessary parts at once?”

In truth, the sudden appearance ex nihilo of these two projects is not entirely convergent evolution. Both teams applied for grants awarded “under the umbrella theme ‘Complex mechanisms of living organisms’” by the Human Frontier Science Program, and each received 1.4 M$ over a period of 3 a. The HFSP awarded 28 grants to begin in 2021.