Pandas, Kitzmiller, and the frozen frog fallacy

Paul Braterman is Professor Emeritus at the University of North Texas and Honorary Senior Research Fellow in Chemistry at the University of Glasgow

This Kitzmas was different. For the first time, the Discovery Institute allowed the anniversary of Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District to pass without complaining about the verdict. Perhaps they are hoping that we will forget about the incredible badness of the text that they were trying to foist on the District’s students. Of Pandas and People is carefully constructed to be as misleading as possible, and we shouldn’t let them forget this, as long as contributors and advisers responsible for it remain in position within the Discovery Institute1, while the Institute continues to promote works such as Denton’s Evolution – A Theory in Crisis, that perpetuate the same elementary errors of logic. But first, an apparent digression. When students first come across the use of molecular or DNA sequencing in constructing phylogenetic trees, they are sometimes puzzled. They have been told that mammals are descended from fish by way of amphibians. Therefore, as a matter of common sense, they might expect that frogs should be closer to fish in evolutionary terms than we are. This is another example of the Evolution as Progress error. While amniotes have progressed through synapsid to mammal to humans, the pinnacle of creation, the frog has remained a lowly frog and should, therefore, be closer to the common ancestor, as if the ineluctable processes of molecular mutation had somehow been suspended. We might call this the “frozen frog fallacy.”

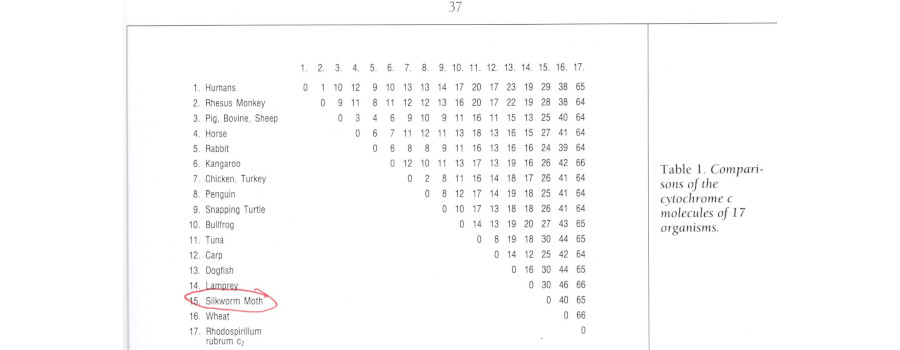

At this point, a Table like the one shown below might help:

All the multicellular organisms shown are, apart from small random fluctuations, at the same distance from the bacterium, as expected if they share a common ancestor distinct from bacteria, which have of course, independently, been accumulating their own set of changes.

All the animals shown are, apart from small random fluctuations, at the same distance from wheat, as expected if they share a common ancestor distinct from plants. And the relative number of mutations shows that the split between plants and animals is more recent than the split between multicellular organisms and bacteria. More recent yet is the split between fish and tetrapods, leaving all tetrapods (including you and me, and of course present-day frogs) at the same distance from the fish. And so on. Most tellingly, humans share a common ancestor with monkeys, more recent than their common ancestor with non-simian mammals. There is a lot more detail in the Table, for example about how to birds relate to reptiles, and how the different orders of mammal relate to each other. And of course the construction of a phylogenetic tree is based on the specific differences found, rather than the overall number.

There are now numerous published studies of the phylogenetic relationships revealed by Cytochrome C, to say nothing of the vast recent literature using numerous molecular and morphological traits to develop detailed high-resolution phylogenies, and to explore the limitations of the concept of a unique phylogeny. What is interesting about the particular Table I have quoted is its origin, and the uses that its authors make of it.

This brings us back to our original theme. The Table actually comes from Of Pandas and People, 2nd edition, 1993, which by the time of the trial had gone through five printings. The book does not give a reference to the source of the data, but much (not all) of the information can be found in a classic 1967 paper [2], which also explains the reasoning behind the method, and critically examines the assumptions made. So there is no excuse for what the book does next, which is to repeatedly assert that the data refute claims of common ancestry:

one might expect analysis to reveal that the cytochromes in fish are most similar to the cytochromes in amphibians. But this is not the case.

And again:

To use the classic Darwinian scenario, amphibians are intermediate between fish and the other band-dwelling invertebrates. Analysis of their amino acids should place amphibians in an approximately intermediate position, but it does not.

(Note the use of Darwin’s name to denote the whole of evolution. In fact, the book is obsessed with Darwin, mentioning him on almost every page, and on some pages up to 10 times. In fact, by my count, and I may have missed a few, Darwin’s name or some variant of it occurs 262 times within the 144 pages of text. This emphasis on Darwin is of course found throughout the whole of the creationist literature, although by now evolutionary theory is almost as different from what Darwin proposed as atomic theory is from that proposed by Democritus.)

These are just two of five separate reiterations of the fallacy, leading up to the extraordinary statement that

Based upon the evolutionary series, we should expect some amphibians to be closer to fish (“primitive” species) and others to be closer to reptiles (“advanced” species).

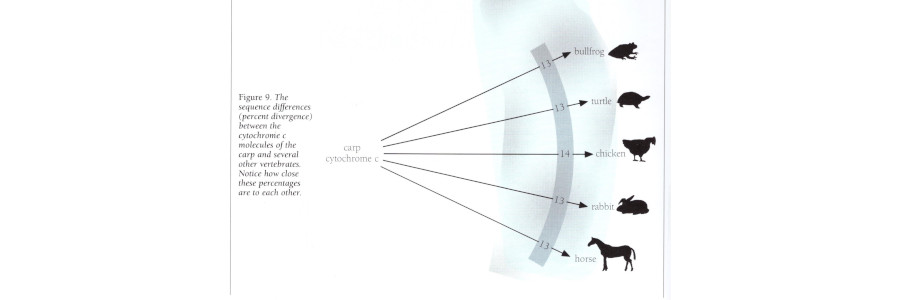

And to make sure that the message sticks, we have this Figure, with the plain implication that the data point, not to evolution, but to separate creation:

The fallacy is not merely being stated; it is being repeated, rationalised, and reinforced. The kindest explanation is that the authors simply do not understand the science that they are presenting, seeing a hierarchical structure where none exists, and imposing on their biology a perspective in terms of “higher” and “lower” which do not belong in modern science, but have been carried over, such as the power of human vanity, from a worldview more akin to Aristotle and the mediaeval Great Chain of Being. The same fallacy also occurs in Michael Denton’s 1985 Evolution - A Theory in Crisis, and while he had by 1998 [3] quietly walked away from this, his 2016 sequel, Evolution – Still a Theory in Crisis, retains his preference for Aristotelian over phylogenetic classification.

And why should this matter? Because it reminds us, and we should not forget, that the Discovery Institute does not only deal in dis-information, but in dis-education.

I thank Maarten Boudry, Glenn Branch, Joe Felsenstein, John Harshman, Kim Johnson, Larry Moran, and Massimo Pigliucci for helpful comments and links to the literature.

Footnotes and citations:

(1) Dean Kenyon (co-author), Charles Thaxton (Academic Editor), and Stephen Meyer, Michael Behe, and Nancy Pearcey (contributors) all hold positions at the Discovery Institute, as do Raymond Bohlin, Walter Bradley, Robert Kaita, J.P. Moreland, and Paul Nelson, who are on the list of those thanked for being “critical reviewers”, as, also, are Meyer and Behe.

(2) Walter M Fitch and Emanuel Margoliash, Science 155(3760), 279, 1967; DOI: 10.1126/science.155.3760.279

(3) For a discussion of Denton’s revised position, see this 2006 post at Larry Moran’s Sandwalk blog