Fisher, Fitness, and the Fundamentals of Population Genetics

Zachary Hancock is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan and specializes in evolutionary genetics.

Evolution by natural selection requires that there exists variation in fitness between individuals. This simple truism goes back to Darwin’s Origin of Species, but where Darwin relied on verbal arguments, the statistician and population geneticist R.A. Fisher sought to codify this basic fact mathematically.

In 1930, Fisher published The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, and within introduced the fundamental theorem of natural selection (FTNS). The FTNS is, in effect, a restatement of Darwin’s idea on the reliance of natural selection on variation. In words, the FTNS states that the rate of change in a population’s average fitness is equal to the additive genetic variance in fitness at that time. An implication of this is that when there’s a ton of variation in fitness, the population’s average fitness can increase rapidly by natural selection. But if there is very little differences in fitness among individuals, any subsequent fitness increase must be slow or absent entirely.

The basic idea behind the FTNS is quite simple, even if the derivation mathematically has caused many biologists to scratch their heads over the many decades since Fisher first introduced it. Some, like Warren Ewens (Ewens 1989), have argued that Fisher’s theorem is useless, while others, such as George Price (Price 1972), Alan Grafen (Grafen 2003), and Sean Rice (Rice 2004) have contended it is, indeed, a general theorem properly understood. Point here is that the FTNS has been a source of much debate for decades.

In 2018, two creationists wandered into this rather esoteric historic dispute. And as is characteristic of creationists, they did so without a clear appreciation of the field they were embarking to critique and with highly suspect motivations. Bill Basener—a mathematician and data scientist at the University of Virginia—and John Sanford—retired Cornell plant geneticist, inventor of the gene gun, and promoter of “genetic entropy”—together (and “BS” hereafter) published a paper in the Journal of Mathematical Biology titled “The fundamental theorem of natural selection with mutations.”

They had two goals. First, they wanted to hype the FTNS—they claim that it offered “mathematical proof of Darwinian evolution,” providing what they believed was the much sought after mechanism for perpetual fitness increase. Remember, to BS the definition of fitness is something like “net information” or “net functionality” (Basener et al. 2021). That is, a bacterium is simpler than a catfish, and thus has lower fitness. So, to them, the FTNS was an attempt to show how a bacteria-like organism can “progress” into something fancier and more complex (“from goo to the zoo to you,” as the saying goes).

Second, they wanted to show that actually the FTNS is incomplete because it doesn’t consider where new mutations come from, and what their effect on fitness might be. And now we’ve moved from the enigmatic FTNS to, for readers of Panda’s Thumb, the much more familiar territory of genetic entropy. That’s right: BS add their own distribution of fitness effects (DFE) to the FTNS—one highly skewed towards deleterious alleles with a fraction of beneficial mutations of only 0.001—and then, using numerical simulations, show that fitness is expected to decline.

The punchline of BS is that the FTNS, while touted as a mathematical proof of Darwinian evolution, was actually derived under questionable assumptions (e.g., no dominance or epistasis) and when “corrected,” actually predicts fitness should decrease. Creationist news agencies had a field day with headlines such as “A Mathematical Proof of Darwinian Evolution Is Falsified” and “Flipping Fisher’s Famous Theorem.” Rob Carter of CMI published a YouTube video titled “Fisher’s failure and the dramatic end of Neo-Darwinism.” Juicy stuff.

While many defenders of evolutionary biology have responded—including Joe Felsenstein and Mike Lynch—these responses were either in blogs or in video format and tended to focus on the “genetic entropy” part of BS and argue that the FTNS was not foundational in any sense, given that most of the mathematics of natural selection had been derived in the preceding decades. Ultimately, the status of the FTNS is immaterial to the “creation-evolution debate.” Fisher could’ve been dead wrong in his derivations and evolution—as understood by biologists—would still be true, and natural selection would still rely on variation in fitness to work. Overturning Fisher’s theorem does nothing to challenge Darwin’s original argument. Genetic entropy, on the other hand, is a critique with more substance.

But as both a population geneticist and a student of history, sympathetic to the view of Sean Rice and Alan Grafen of the generality of the FTNS, I couldn’t let BS slide. And BS (2018) is the closest Sanford has come to publishing his “genetic entropy” model in the peer-reviewed literature, so it seemed that we could kill two birds with one stone.

Dan Stern Cardinale of Rutgers and I decided to pen a response to BS, which has been published in JMB titled Back to the fundamentals: a reply to Basener and Sanford 2018 (the title serves as a play on Fisher’s fundamental theorem and the obvious fact that BS have severely misread The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, which many consider to be next in line in the great books on evolution to only Darwin’s own magnum opus.

First, we had to clarify the assumptions of the FTNS. While BS contend it’s severely limited in its generality and assumes no dominance, epistasis, environmental effects, etc., we show that none of these are prerequisites for deriving the FTNS. To demonstrate this, we start from the famous Price Equation, which some have called the fundamental theorem of evolution (Queller 2017). We start here because the Price Equation is derived with no simplifying assumptions—it is a true general theorem. In words, it is:

[rate of change of the average of some trait] = [covariance between that trait and fitness] + [difference between parent-offspring trait average]

First, while fitness can be defined in many ways, in Price’s equation it is simply the number of offspring a parent leaves. Second, a covariance can be thought of as the shared change between two variables; for example, if longer fur is beneficial in a cold environment, then there will be a positive covariance between fur length (the trait) and how many offspring you leave (fitness). In this way, the Price Equation captures natural selection in the covariance term.

The FTNS is easily derived from this equation by simply letting “trait” be “fitness,” since parental fitness is expected to covary with offspring fitness—that is, fitness is heritable. Rewriting:

[rate of change of average population fitness] = [covariance between parent and offspring fitness] + [difference between parent-offspring trait average]

Notice how this looks much like the definition of the FTNS stated earlier. The “covariance” term can be clarified if we remember a simple mathematical identity. Some might be familiar with the concept of linear regression; this is when you fit a straight line through a plot of points such that the line minimizes the distance between all the points. It turns out, the covariance between two terms (like parent and offspring fitness) is equal to the slope of that line multiplied by the variance in parent fitness. Again, variance here is simply the mean of the squares of the spread of values around the average—high variance means there is high variation around the average value.

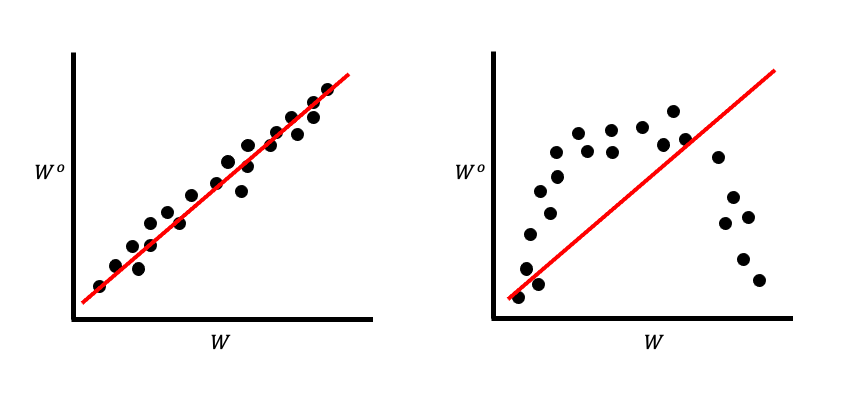

Since linear regression is a straight line, we call the variance that they capture the additive genetic variance. This means that irrespective of the genetic architecture of a trait, selection acts to shift the mean of that trait as if it were simply additive. Consider the simple plot in Figure 2.

Notice the slope of these is exactly the same, despite the trait clearly not being an additive trait in the second plot. Here, an “additive trait” means one in which every genetic locus contributing to the trait value does so as a simple sum.

It’s important to remember that we are not performing a linear regression in the statistical sense of fitting a line to some data. Instead, we are relying entirely on mathematical identities: the definition of a covariance is [slope of a straight line as determined by least squares] × [variance of the independent variable].

By replacing the covariance term with this “additive genetic variance” term, we arrive at the classic way of viewing the FTNS: the rate of change in mean population fitness is equal to the additive genetic variance in fitness at that time. No simplifying assumptions were introduced. Fisher’s theorem is, it turns out, a general theorem, contrary to BS. Further, we see that the FTNS does not rely on there being no dominance or epistasis–it’s simply that natural selection acts on the additive variance irrespective of these. As James Crow once remarked, “Nature discovered least squares long before Gauss” (Crow 2008).

Next, we deal with BS’s claim that Fisher thought fitness would perpetually increase and that he viewed the distribution of mutational effects as symmetrical, equal parts beneficial and equal parts deleterious. It’s easy to debunk these ideas with Fisher’s own words. In The Genetical Theory, Fisher writes: “Against the rate of progress in fitness must be set off, if the organism is, properly speaking, highly adapted to its place in nature, deterioration due to undirected changes either in the organism, or in its environment. The former, typified by the pathological mutations observed by geneticists… The latter, due to… changes in the organic environment, including improvement of enemies and competitors… may be in effect either greater or less than the improvement due to Natural Selection” (Fisher 1930). So clearly, Fisher thought that there were other forces in nature that could counterbalance natural selection, and hence the FTNS couldn’t be a “mathematical proof” of perpetual fitness increase. It only serves to illustrate that natural selection, as a single component, acts to increase fitness.

We then introduce Fisher’s geometric model of adaptation to counter BS’s claim that Fisher thought the effects of mutations were symmetrical. To understand Fisher’s model, imagine a landscape of phenotypes that have valleys of low and peaks of high fitness. Moving across this phenotypic landscape is akin to changing the mean phenotype of the population. If you are far from a fitness peak, then taking a big step through the landscape (that is, a mutation of large effect on the phenotype occurs) is equally likely to move you in the right direction as in the wrong. But if you’re on a peak, large effect mutations almost always take you off the peak. Hence, the effects of mutations are context dependent, and the context is how well adapted the population already is to the environment they’re in.

This is quite a different picture than how BS present Fisher’s views, and indeed how creationists often view the distribution of fitness effects (DFE). While they tend to present it as some fixed distribution, evolutionary biologists have never seen it that way; the effect of any mutation is dependent on the context in which it arose, both with respect to the environment but also with respect to the optimality of the trait in question.

So, BS fumble Fisher’s views on mutations and fitness increase, and make false claims as to the assumptions necessary to derive the FTNS. The last thing we deal with is their claim that the FTNS, when it incorporates real mutational distributions, predicts fitness decline, not increase.

Those familiar with Sanford’s “genetic entropy” model will already know where this is going. BS rely on a DFE from Kimura (1979) which was used to model effective neutrality and has no beneficial mutations; they add a tiny fraction—0.001—to that distribution and call it “real.” And, as stated above, they find fitness declines.

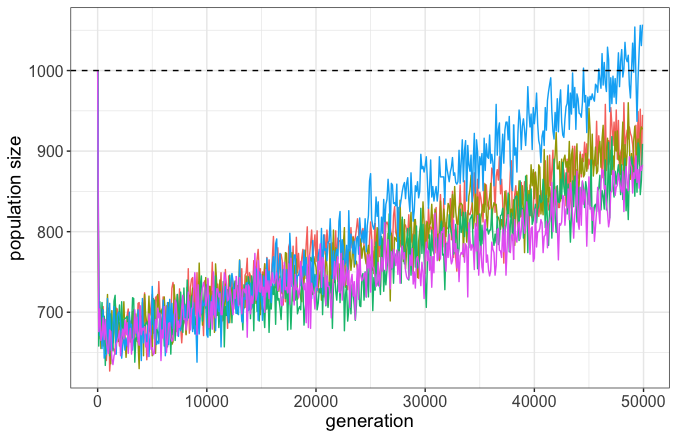

Since BS (2018) has been touted as a peer-reviewed paper supporting genetic entropy, we decided to perform our own simulations as a direct response with the (naïve) hope that it puts genetic entropy out to pasture once and for all. We pull distributions from several empirical studies, modelling the deleterious fraction as gamma-distributed and the beneficial as exponential, with 99% of all mutations strictly deleterious. Of the beneficial fraction, the mean effect is only 0.001, and so most merely act to compensate for the loss of fitness from the deleterious. Fitness is absolute in our simulations, so as the population accumulates deleterious mutations, it can slowly go extinct. We run our simulations for 50,000 generations.

In opposition to BS, not only did our populations not go extinct, but actually grew in size (Figure 3). While the vast majority of mutations were deleterious (and many fixed!), the overwhelming preponderance of mutations that fixed were beneficial due to positive selection. This is because the probability of fixation of beneficial mutations always exceeds that of deleterious, even if they are approximately equal as |s| = 1/(2N), where s is the selection coefficient and N is the population size.

Creationists often tout studies showing that the vast majority of mutations are deleterious as evidence of genetic entropy. But as many have argued in the past and as our simulations show, this is neither an impediment to evolution nor a hinderance on adaptation. Fitness can still increase despite deleterious mutation pressure because of natural selection. Indeed, this brings us back to the FTNS: since there are differences in the fitness of individuals, and those differences are heritable, natural selection can act to increase the population’s mean fitness.

In the end, BS misrepresent Fisher’s theorem by claiming it needs to be expanded to include mutations to introduce genetic entropy into a peer-reviewed journal. We argue in the last section of the paper that the “real target” of their assault on the FTNS was actually universal common descent. We expose this by simply letting their other publications speak for themselves, citing numerous examples in which they misrepresent both “fitness” and “Darwinian evolution.”

We hope that this reply to BS serves to undermine the credibility of the original paper. And, in the end, clarify an important and often debated concept in evolutionary biology—the fundamental theorem of natural selection.

References

Basener, W. F., & Sanford, J. C. (2018). The fundamental theorem of natural selection with mutations. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 76(7), 1589-1622.

Hancock, Z. B., & Cardinale, D. S. (2024). Back to the fundamentals: a reply to Basener and Sanford 2018. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 88(5), 1-20.

Queller, D. C. (2017). Fundamental theorems of evolution. The American Naturalist, 189(4), 345-353.

Basener, W., Cordova, S., Hössjer, O., & Sanford, J. (2021). Dynamical systems and fitness maximization in evolutionary biology. In Handbook of the Mathematics of the Arts and Sciences (pp. 2097-2169). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Fisher, R. A. (1930) The genetical theory of natural selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Ewens, W. J. (1989). An interpretation and proof of the fundamental theorem of natural selection. Theoretical population biology, 36(2), 167-180.

Grafen, A. (2003). Fisher the evolutionary biologist. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series D: The Statistician, 52(3), 319-329.

Rice, S. (2004). Evolutionary theory: mathematical and conceptual foundations. Sinauer Associates, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Crow, J. F. (2008). Commentary: Haldane and beanbag genetics. International journal of epidemiology, 37(3), 442-445.