How humans lost their tails

Joel Eissenberg is a professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. His research interests include transcriptional control of gene expression and vesicle trafficking. He has had a lifelong fascination with genomics and with developmental biology.

In a recent Nature paper, Xia et al. offer a mechanistic explanation for tail-loss evolution in humans and anthropomorphous apes. It turns out that loss of a tail is caused by loss of a gene function among the tailless primates. And as the paper shows, this evolutionary transition was mediated by transposable elements, that is, repeated parasitic DNA fragments that are found in all living things.

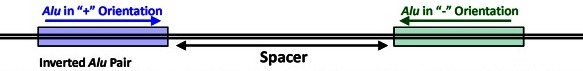

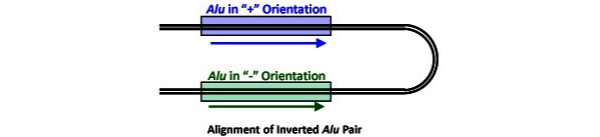

The starting point of the study was the comparative anatomy of a certain locus known as TBXT in tail-bearing simians and tailless apes. All simians display a copy of a short DNA sequence, called Alu, in the middle of the gene. Alu elements are the most abundant transposable elements (“jumping genes”) in the human genome; they first appeared about 65 million years ago and are widely dispersed throughout our genomes. Copies of Alu frequently interrupt genes with no apparent consequences. But in tailless apes, there’s an additional copy of Alu a little farther down and in the mirror image orientation from the copy common to all simians. The hypothesis driving this paper is that the Alu elements pair with one another, causing some of the information produced by the gene to be omitted by interfering with proper expression. Tailless primates express both this defective gene product and full-length TBXT gene products. The inference is that transposable-element–mediated defects in TBXT gene function underlies the evolutionary loss of external tails in hominoids.

Creationists should perhaps note that the authors set out to test their conjecture using genetically engineered mice. Simply deleting the region between the human transposable elements in the mouse version of TBXT results in mice with variable truncation of tail length. The next step was to test whether inserting the human transposable element sequences in the mouse at the corresponding sites of the mouse TBXT gene recapitulates human taillessness. To further test whether it was the Alu sequences per se that mattered, mice were engineered with repeated DNA sequences of the same length as Alu, but unrelated in sequence at the sites and orientations corresponding to the human transposable elements. The point was to test whether there’s something special about the Alu sequences or whether any DNA sequence of similar length and positioned at the same sites in mirror image symmetry will do.

When mice engineered such that their own TBXT gene was flanked by human Alu sequences in a fashion resembling the situation at the human TBXT locus, their descendants showed normal tails. Interestingly, descendants of mice engineered with the flanking repeat sequences unrelated to Alu had tails 10% shorter than wild-type mice. Detailed analysis of gene expression suggested that the ratio of normal to abnormal gene products was important to tail truncation. Further crosses generated mice with a combination of gene products that resulted in tailless mice. The upshot of all this is that (1) the chance insertion of a second Alu element in the common ancestor of tailed and tailless simians can explain the loss of external tails in the latter, and (2) the pairing of inverted copies of DNA sequence repeats accounts for the aberrant TBXT gene products – not some special property of Alu sequences.

The idea of transposable elements as sculptors of genomes is not a new one. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the ends of chromosomes are maintained by transposable elements. The Nobel laureate Walter Gilbert proposed that some genes evolved from pieces of transposable elements. In this study, we see yet more evidence that transposable elements can drive evolution.