Looking for Mr. Goodlink? Re-examining the “Standing” of Sahelanthropus

Andrew J Petto is Distinguished Lecturer Emeritus in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, where he taught anatomy and physiology, human gross anatomy, and kinesiology courses. He is a bioanthropologist with a concentration on primate functional morphology. His latest book, as a co-author with Alice Beck Kehoe, is Humans: An Introduction to Four-Field Anthropology, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. 2022 (Dec).

The story of Sahelanthropus tchadensis is the story of the emergence of the human evolutionary branch from the last common ancestor of the African ape clades (evolutionary branches): humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. It is a story of transitions. To understand the importance of Sahelanthropus in reconstructing human evolutionary history, we could paraphrase Dobzhansky’s famous quotation: “Nothing in Sahelanthropus biology makes sense except in the light of evolutionary transition” (Dobzhansky 1973).

Since its discovery in 2001, Sahelanthropus tchadensis has intrigued scientists (Brunet et al. 2002). Nicknamed “Toumai” which means “hope of life” in the local language, it is (so far) the oldest fossil on our human evolutionary branch, and it is very close to the time when this evolutionary branch separated from the last common ancestor with the other African great apes.

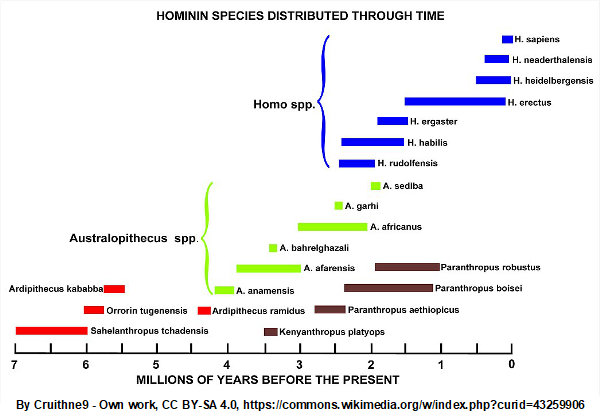

Sahelanthropus is located at the bottom left of the chart in Figure 1, living between 7 and 6 million years before present. (A quick overview of the major findings about this species is available here.)

A lot of the fossil remains reflect what we might expect for a human ancestor at this very early stage of human emergence: a mixture of features that are common to all the African apes, some that are modified from the ancestral form that appear differently from their appearances both in the human and great-ape branches, and several specific modifications of ancestral features that we have never found outside of the human branch.

But there is still very little fossil material from this species, and we have a lot of questions that we cannot answer based on the material we have. Answers to some of these questions—when they finally come—will tell us important things about how early humans made the transition to the peculiar ape descendant that we are today. Others will tell us more about evolution as a process.

That is why there is a lot of debate within the scientific community about this species. The scientific debate is not about whether Sahelanthropus is an early member of the human evolutionary branch, but about what these remains can tell us about the evolutionary journey from the last common ancestor between humans and our closest ape relatives to our own species.

One of the key questions for human paleontology is when our ancestors first became committed to walking upright on two legs. The most recent discussion of Sahelanthropus is about what the available fossil material can tell us about this important human adaptation (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology 2024).

Ongoing field work and excavation have added a few more remains to the original finds, but the entire collection attributable to Sahelanthropus remains quite limited. Some questions can be answered by continuing study of the available remains, but for others we can only find final answers if and when we discover more preserved material from more individuals (and maybe from more locations).

What is a human?

Part of what we need to know to answer our questions about Sahelanthropus is “What, exactly, is a human?” (for example, Smithsonian Institution 2024; LeMaître et al 2022). And another important question for understanding the early stage of the emergence of the human evolutionary branch is “How many of all the features that are unique to modern humans does an organism need to have in order to be considered human?”

For any hominin so soon after (or maybe still in the process of) branching off from the African great apes, we would look for a number of features that appear only in the human branch of the family modified in a way that is different from how it appears in the other branches. The organism doesn’t need to show everything that separates humans from other apes, only things that are undisputedly found only in humans and not in our closest ape relatives.

Brunet and his team describe a list of these features in the skull, jaws, and teeth that they excavated (Brunet et al 2002). Guy et al (2005) provide data tables and graphics to show the mosaic of features that tend to be different between humans and African great ape species. It should not be surprising that Guy et al (2005) demonstrate that some of these features in Sahelanthropus are more similar to those of humans (living and fossil), some of them are more similar to African great apes, and the rest are somewhere in between.

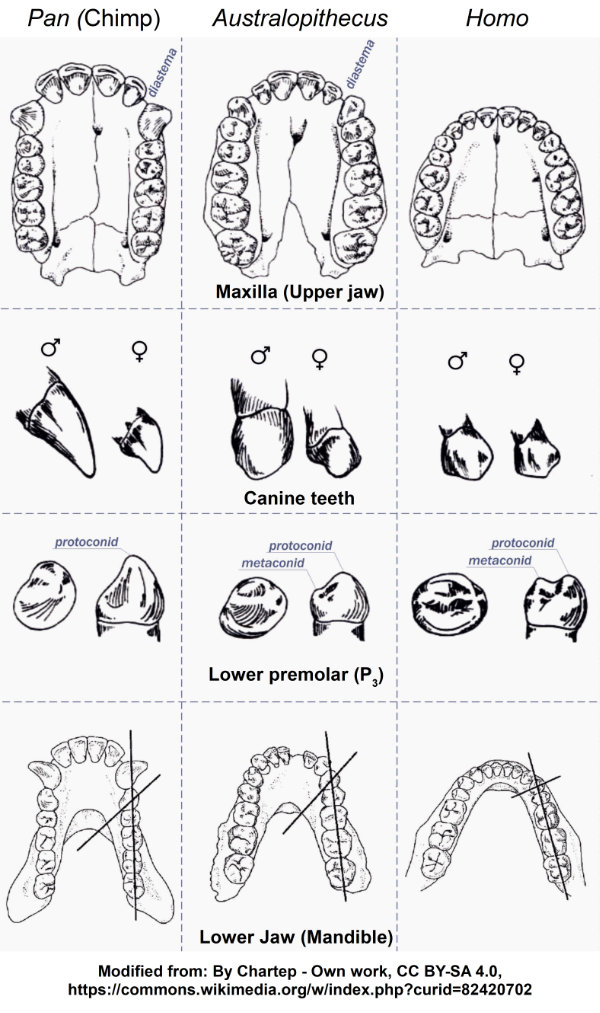

A few particulars stand out. One major change in almost all the members of the human branch is in the canine teeth in the upper jaw and how they work with the canine and first premolar in the lower jaw. In hominins, the crowns and roots of the upper canines are smaller than in African great apes, and the upper and lower teeth tend to meet their opposites crown-to-crown. The earlier members of the hominin branch will show the tendency for this change, but the process will not be complete for a few million years.

Additional materials from teeth and lower jaws (Brunet et al 2005) confirmed the analysis in the original reports (Brunet et al 2002) that the upper canine was reduced compared to African great apes (though still somewhat longer than the adjacent teeth), and the arrangements of teeth in the lower jaw were consistent with the pattern in later hominins, rather than in the great ape evolutionary branches most closely related to humans.

One of the most important dental changes was a reduction in the gap (diastema) in the upper jaw between the canine and the lateral incisor where the lower canine would fit when the jaw is closed. In the other primates, the upper canine then slides between the lower canine and first premolar and meets in an interlocking arrangement. This arrangement allows a shearing action when the jaw is closed. These species also show a “honing” surface when the upper canine slides past the lower first premolar to help maintain an edge on the canine.

The diastema in the upper jaw and the honing surfaces in the lower jaw are both reduced in all fossil hominins and absent in living hominins (Guy et al, 2005), as shown in Figure 2. In addition, Figure 2 shows the change in shape of the first lower premolar (labeled as P3). The surface where the upper teeth make contact with P3 changes from the part of the tooth oriented toward the front of the jaw to the crown facing the upper jaw. The overall shape of the crown in P3 in hominins resembles molars more than it does the canines and incisors that perform cutting, slicing, and piercing actions.

One of the key issues in recent exchanges on Toumai concerns changes in human anatomy and behavior related to the way that we walk: standing upright and striding on two legs—technically known as obligate bipedal orthogrady. This means that we walk on two feet and carry our spines perpendicular to the ground, and that no other way of walking is a practical option.

For Toumai, the parts of the skeleton that give us direct evidence for this behavior are scant, but a recent analysis of thigh bones has been the focus of a mild dispute (see Daver et al 2020; Meyer et al 2023; Cazenave et al 2024). The dispute is over whether there is strong evidence of skeletal adaptations for bearing all the body’s weight only on the legs. Furthermore, a recent analysis of an ulna from the forearm suggests that Sahelanthropus was bearing weight on the arms at least a significant part of the time (Karoui Canedo et al 2023).

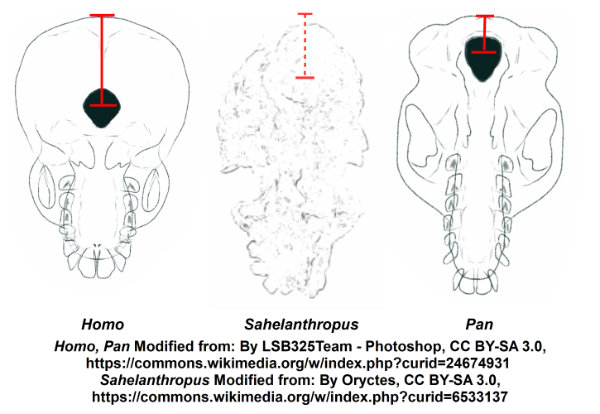

Though there are very few specimens involved, the evidence that these studies present is that Sahelanthropus had not transitioned to standing upright and striding on two legs. Nevertheless, the base of the skull shows an important change associated with an upright posture (Guy et al 2005). The opening in the skull to allow the spinal cord to enter the brain case—the foramen magnum—is shifted forward. In humans, we usually associate this change with upright walking (for example, Neaux et al 2017), because when the spinal column is held perpendicular to the ground, placing the joint between the base of the skull and topmost vertebra under the middle of the skull instead of toward the back allows us to balance our heads with our eyes forward when we stand upright.

There are several other changes in the base of the skull that go along with bipedalism (see for example, Kimbel and Rak 2010). These researchers report that even in Australopithecus afarensis at 3.7 million years ago—though the foramen magnum and the joint surfaces that allow the skull to work with the first of the vertebrae have moved forward into a position typical of fully bipedal modern humans—a number of other important changes in the base of the skull have not yet been made (and, of course, Sahelanthropus lacks these modern touches, as well).

The position of the foramen magnum in Sahelanthropus is moved forward compared to its location in the African great apes, but not as far forward as we see in later hominins (Guy et al 2005). Although it is common to say that the more forward position of the foramen magnum is indicative of upright walking (for example, Sahelanthropus SI 2024), the evidence from comparative anatomy of the primates indicates that it is rather more indicative of an upright posture, as we see in several prosimian primate species.

These primates do not “walk” upright—they may climb vertical trunks, leap vertically from one tree to another, or clamber holding onto branches above and below as they move— but their preferred posture is to hold the spinal column perpendicular to the ground, and the result is that the foramen magnum is shifted closer to the front of the skull (Russo and Kirk 2013).

What we can conclude from the relative position of the foramen magnum is that Sahelanthropus was accustomed to a more upright posture, even if further evidence from the limbs, wrists, hips, knees, ankles, and feet may someday tell us that bipedal striding was not the preferred way of getting around. Could they walk upright? Perhaps, but the available materials from the limbs suggest that they would probably find it difficult. Of course, that does not mean that they could not do it at all.

For modern humans, we know that walking on two legs is our most efficient way of moving. However, we can swim, brachiate like gibbons, climb trees like monkeys, hop like sifakas, leap like bush babies, and move in a lot of different ways on the ground, in the trees, and in the water. It is just that we aren’t particularly good at these ways of moving compared with other animals for whom any of these is their primary mode of locomotion.

So maybe what later hominins inherited from ancestors like Sahelanthropus—or more accurately from the populations of early hominins that were pioneering the anatomic changes that are underway in Sahelanthropus— was not a particular style of locomotion, but a preference for a particular posture, and that preference led to adjustments in ways of walking.

An intriguing possibility for this preferred posture is a behavioral pattern called “extended limb clambering” in Miocene apes—walking on top of a limb while holding onto the limb or branch above oneself (Zhang et al 2024; Böhme et al 2019). Like the illustration at the beginning of this article, Böhme et al (2019) inferred from skeletal anatomy that the Miocene ape species Danuvius guggenmosi moved through the trees supporting the upper body using its arms to grasp limbs and branches overhead and supporting its lower body using its legs on branches below. This type of locomotion would preserve the preference for an upright posture, but not require the skeletal specializations necessary to stride along the ground on two legs. Those could come later if moving on the ground became an integral part of life in the descendants of at least some Miocene apes.

Recent work on the balance organs of the inner ear gives us another way to assess the transition to bipedalism. Studying the anatomy of the inner ears of fossil and extant primates suggests that the semicircular canals of the inner ear show changes associated with “agility” in movement—that is, carrying out complex movements in multiple dimensions as one might have to do moving among tree trunks, limbs, and branches that do not form a continuous flat surface (Zhang et al 2024; Silcox et al 2009; Spoor et al 2007).

The three semicircular canals detect changes in speed and direction of movement relative to the three dimensions of space. Movements through complex environments like trees require changing the relative positions, speeds, and directions of arms, legs, trunks, heads, and necks during locomotion and produce a lot of changes that the inner ear monitors.

The information from detecting the movement of fluids in these canals is transmitted to various reflexes and to integrating centers in the brain. The brain then coordinates senses and movements so that the individual can continue to focus on the intended direction of movement and on specific features for navigating through the environment, even as the body changes its orientation and direction frequently. To succeed in their environments, arboreal primates have longer and wider canals than terrestrial ones (relative to body size). Smaller semicircular canals indicate more commitment to simpler locomotor behaviors, for example, walking in a single direction in a plane.

As we might expect, modern humans tend to have smaller and thinner canals than other primates, when adjusted for body size, suggesting less adaptive pressure for “agility” from complex environments. In the modeling reported by Zhang et al (2024) the rate of change in the size and shape of the semicircular canals increased significantly in hominins about 3.6 million years ago—at about the time when we have undisputed evidence—both anatomic and from footprints—that Australopiths were fully bipedal and at the foundation of a series of anatomic specializations that would make this way of walking more efficient over the next few million years.

The form of the semicircular canals in Sahelanthropus is not yet known. The imaging of this structure is complex, and when skulls are distorted by post-burial pressure it is even more difficult to assess their size, shape, and proportions. However, since skulls are common in the fossil record, the ability to detail the anatomy of the semicircular canals would be useful in determining whether Sahelanthropus engaged in the more complex array of behaviors seen in arboreal apes or in the more limited set that are typical of bipedal hominins.

Is Toumai a “missing link”?

One of the most persistent misconceptions about evolutionary change is the concept of “missing links”—organisms that appear as some sort of half-finished transition between ancestors and descendants. The inference is that there should be an uninterrupted series of transitional organisms from one species to another. The more serious error is the failure to see species bearing a mix of transitional features as unique living organisms in their own right, with a suite of biologic and behavioral features that embody an environmental role in relationship to other contemporary species, rather than just as stepping stones on the way to some projected end point: in this case, modern humans.

This misconception is based on two fundamental misunderstandings of modern evolutionary biology. The first misconception is that evolution is a process in which individuals in one species “turn into” another species, and therefore we ought to see an infinite array of “links” illustrating each of the steps in that process. This leads to the expectation of a “smooth” series of stepwise changes. Any apparent gaps in the expected steps are conceived of as “missing” links in the process.

The second misconception is a typologic view of species in which all members of a species are defined by the characteristics of the type specimen—an idealized concept of the defining features of the species. This leads to the unrealistic expectation that that there will be clear boundaries distinguishing one species from another in an evolutionary series. In this case, the “gaps” among species appear when examining the “types” but may be quite a bit less impressive when we consider all the variation among the known members of a species—especially those that deviate the most from the type specimen.

Biologic variation among individuals in populations (and in species) is one of the most fundamental properties of all life on Earth. How much anatomic variation can we accept within a single species? How different from each other must two specimens be before we can agree that they are different species? We know from DNA analysis that modern Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans mated with each other when the populations encountered each other. Apparently these people did not see themselves as separate species even though some in the scientific community may disagree!

Despite the differences in these misconceptions, when a specimen shows affinities for more than one branch in the tree of life, the reaction is to demand that we come up with the specific features that tell us on which one of the branches (and where on that branch) such specimens lie. People want to know the ancestry that links a particular species to its relatives in the past and the future (and this means identifying the intermediates). As in the case of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, answering this question is especially a problem when there is only a very small sample of skeletal remains and when the closest relative in the family tree—in this case, Orrorin tugensis — is located close to 1 million years and 2700 km away.

We have only a very limited sample of all the ways that important features can vary among members of this species. The analysis of Macchiarelli et al (2020) shows us how putting this specimen in the context of the range of variability in hominin species allows us to be confident that Sahelanthropus is an early hominin whether or not it was fully committed to upright walking.

As a very early member of the hominin clade, this species—as one should expect—shows overall anatomic features that strongly resemble those of the African great ape species in this geologic epoch (the Miocene, Polly et al 1994). Sahelanthropus clearly shows that some anatomic changes that separate humans from the other African great apes have begun to appear in these late Miocene populations.

By the time that Orrorin tugensis appears, anatomic changes in the neck and the shaft of the femur show that this bone is responding to the stresses of habitual upright walking (Pickford et al 2002; Richmond and Jungers 2008). This means of locomotion has become common enough in at least one evolutionary branch of humans to show that the bone is responding to the mechanical stresses from bearing the whole weight of the body only on the two legs. These bones were reinforced and thickened in a characteristic pattern shared by bipedal animals, even though many aspects of the bones themselves show a mixture of physical features that resemble those of both Miocene apes who lived earlier and Australopiths who came later (Almécija et al 2013).

Walking Points?

The takeaways from the arguments on bipedalism in Sahelanthropus are these.

In the end, whether Sahelanthropus walked bipedally or not is an interesting question that needs more indisputable evidence. For now, there are strong hints of habitual upright posture in this species. Even so—however far along the trajectory of bipedalism Sahelanthropus has progressed—we should expect the anatomic features to be mixed at this early stage of the transition.

What is important is that Sahelanthropus is a species showing some features unique to hominins or intermediate between humans and African great apes mixed with features that are common in all the African great-ape branches. In other words, it is a species in transition. Toumai shows us that this transition was underway at least a million years before we have the first direct anatomic evidence of adaptations to upright walking—so far. What Sahelanthropus does is to give us a glimpse into some of the anatomic and behavioral changes that shaped the emergence of the human evolutionary branch.

As with any evolutionary branch in transition, membership in the human branch of the evolutionary family does not depend on possessing any one anatomic feature or complex—even one as distinctive as bipedalism. Even if Sahelanthropus did not walk fully upright, it is still a valuable example of biologic variation and evolutionary change near the time of emergence of early humans from their last common ancestor with the African great apes!

Acknowledgment. Thanks to Prof Benjamin Campbell in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee for comments, questions, and suggestions.

References.

Almécija S, Tallman M, Alba DM, Pina M, Moyà-Solà S, Jungers WL. The femur of Orrorin tugenensis exhibits morphometric affinities with both Miocene apes and later hominins. Nature Communications. 2013:4(1):2888. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3888

Böhme M, Spassov N, Fuss J, Tröscher A, Deane AS, Prieto J, Kirscher U, Lechner T, Begun DR. A new Miocene ape and locomotion in the ancestor of great apes and humans. Nature (London). 2019;575(7783):489–493. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1731-0

Brunet M, Guy F, Pilbeam D, et al. A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature (London). 2002; 418(6894):145–151. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00879

Brunet M, Guy F, Pilbeam D, Lieberman DE, Likius A, Mackaye HT, Ponce de León MS, Zollikofer CPE, Vignaud P. New material of the earliest hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad. Nature. 2005; 434(7034):752–755. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03392

Cazenave M, Pina M, Hammond AS, Böhme M, Begun DR, Spassov N, Gazabón AV, Zanolli C, Bergeret-Medina A, Marchi D, Macchiarelli R, Wood B. Postcranial evidence does not support habitual bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis: A reply to Daver et al. (2020). [Commentary]. Journal of Human Evolution. 2024 (in press); 103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103557.

Daver G, Guy F, Mackaye HT, Likius A, Boisserie J-R, Moussa A, Pallas L, Vignaud P, Clarisse ND. Postcranial evidence of late Miocene hominin bipedalism in Chad. Nature (London). 2022; 609(7925):94–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04901-z

Dobzhansky T. Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. American Biology Teacher. 1973;35(3):125–129. doi:10.2307/4444260.

Guy F, Lieberman DE, Pilbeam D, de León MP, Likius A, Mackaye HT, Vignaud P, Zollikofer C, Brunet M. Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS. 2005;102(52):18836–18841. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0509564102

Karoui Canedo J, Daver G, Blasi-Toccacceli A, Clarisse ND, Likius A, Mackaye HT, Moussa A, Mahamat A, Pallas L, Surault J, Guy F. Ulnar morphology in Sahelanthropus tchadensis, what it tells us on the locomotor repertoire of the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees (LCA). Bulletins et Mémoires de La Société d’Anthropologie de Paris. 2024;36(suppl). https://doi.org/10.4000/bmsap.12956

Kimbel WH, Rak Y. The cranial base of Australopithecus afarensis: New insights from the female skull. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:3365–3376. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0070.

Le Maître A, Daver G, Mounier A, Prat S, Villotte S, Noûs C. Peut-on définir l’humanité? Une perspective théorique et empirique. Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris. 2022; 34(2). https://doi.org/10.4000/bmsap.10434

Macchiarelli R, Bergeret-Medina A, Marchi D, Wood B. Nature and relationships of Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Journal of Human Evolution. 2020;149:102898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102898

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. What about bipedalism in Sahelanthropus? Accessed 5 July 2024. https://www.mpg.de/22183908/what-about-bipedalism-in-Sahelanthropus

Meyer MR, Jung JP, Spear JK, Araiza IF, Galway-Witham J, Williams SA. Knuckle-walking in Sahelanthropus? Locomotor inferences from the ulnae of fossil hominins and other hominoids. Journal of Human Evolution. 2023;179:103355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103355.

Neaux D, Bienvenu T, Guy F, Daver G, Sansalone G, Ledogar JA, Rae TC, Wroe S, Brunet M. Relationship between foramen magnum position and locomotion in extant and extinct hominoids. Journal of Human Evolution. 2017;113:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.07.009

Pickford M, Senut B, Gommery D, Treil J. Bipedalism in Orrorin tugenensi revealed by its femora. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2002;1(4):191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1631-0683(02)00028-3

Polly D, Speer B, Smith D, et al. The Miocene Epoch. Understanding Evolution. Berkeley: University of California Museum of Paleontology. April 1994. Updated June 2011. Accessed 9 July 2024. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/tertiary/miocene.php.

Richmond BG, Jungers WL. Orrorin tugenensis Femoral morphology and the evolution of hominin bipedalism. Science. 2008;319:1662-1665(2008). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1154197

Russo GA, Kirk EC. Foramen magnum position in bipedal mammals. Journal of Human Evolution. 2013;65(5):656–670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.07.007

Silcox MT, Bloch JI, Boyer DM, Godinot M, Ryan TM, Spoor F, Walker A. Semicircular canal system in early primates. Journal of Human Evolution. 2009;56(3):315–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.007

Spoor F, Garland Jr T, Krovitz G, Ryan TM, Silcox MT, Walker A. The primate semicircular canal system and locomotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS. 2007;104(26):10808–10812. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0704250104

Smithsonian Institution (SI). What does it mean to be human? Human Characteristics. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution. Updated 3 Jan 2024. Accessed 15 July 2024. https://humanorigins.si.edu/human-characteristics

Smithsonian Institution (SI). What does it mean to be human? Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution. Updated 3 Jan 2024. Accessed 9 July 2024. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/Sahelanthropus-tchadensis

Smithsonian Institution (SI). What does it mean to be human? Orrorin tugensis. Washington (DC): Smithsonian Institution. Updated 3 Jan 2024. Accessed 9 July 2024. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/orrorin-tugenensis

Zhang Y, Ni X, Li Q, Stidham T, Lu D, Gao F, Zhang C, Harrison T. (2024). Lufengpithecus inner ear provides evidence of a common locomotor repertoire ancestral to human bipedalism. Innovation (New York). 2024;5(2):100580–100580. H 8