Confidence in scientists rises

According to the Pew Research Center, confidence in scientists has ticked up slightly, though it remains lower than it was before the pandemic. That is one of the conclusions of a report, Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking, by Alec Tyson and Brian Kennedy. Pew surveyed nearly 10,000 US adults in October and discovered that Americans (mostly) perceive scientists as intelligent, honest, and focused on real-world problems. They see communication as a weak area and think that we are good at working in teams, though how they know about teamwork is a puzzle to me.

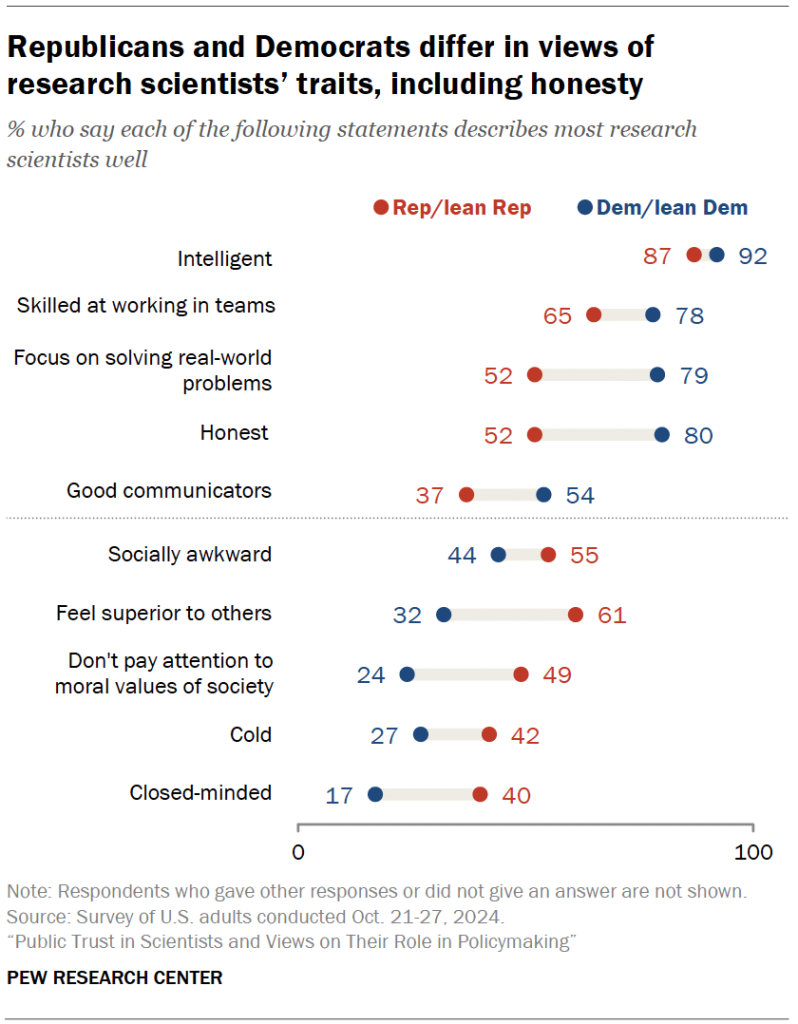

At least they think we are reasonably bright; they also find us socially awkward, cold, superior, and closed-minded. Figure 1 shows how these perceptions break down according to political party: Democrats and their fellow travelers (whom I shall call Democrats) have a considerably more favorable view of scientists than Republicans and their fellow travelers (whom I shall call Republicans). I was somewhat bemused by the claim of roughly half of Republicans that scientists "[d]on't pay attention to moral values of society," and wondered precisely what and whose moral values they have in mind.

Pew notes, somewhat to my surprise,

In an era of low public trust in institutions, scientists continue to be held in higher regard than several other prominent groups we’ve asked about, including journalists, elected officials, business leaders and religious leaders. Confidence ratings for scientists are even slightly higher than those for public school principals and police officers – two groups that receive positive overall ratings. [I did not follow the preceding link.]

Pew also notes differences by race and ethnicity; you may find these by following the link in the first paragraph.

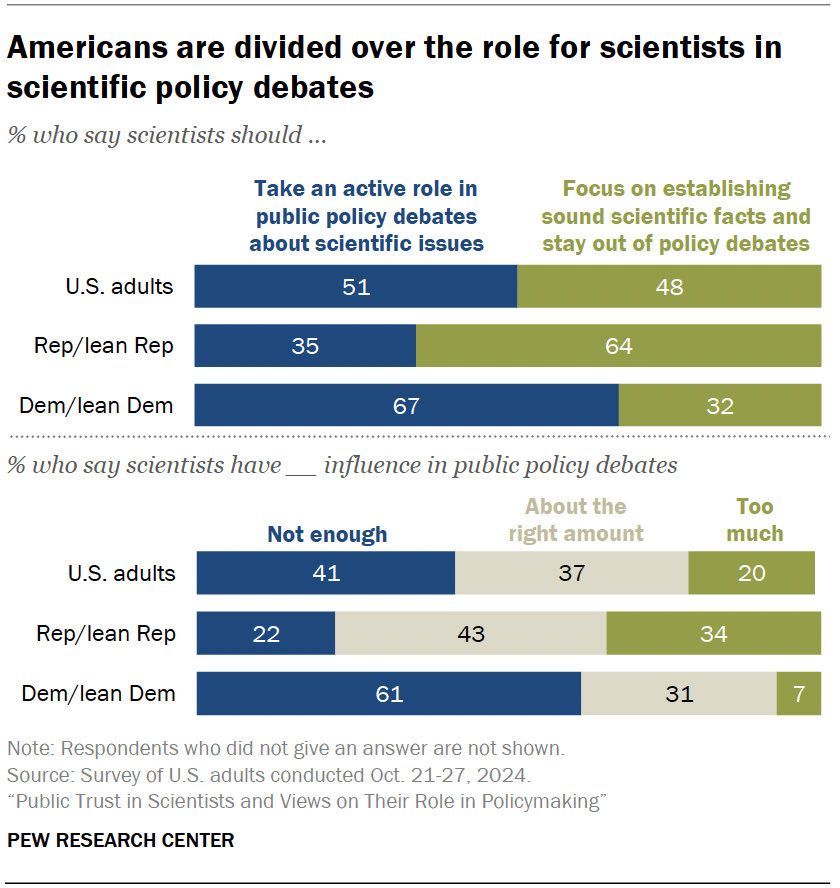

Regarding science policy, I would wager, assuming it is legal to do so, that a very significant fraction of those reading this article would privilege scientists over laypersons when it came to setting science policy. Figure 2 shows that almost exactly half of the respondents to the Pew survey disagree with that contention and think that scientists should stay out of policy. Only about one-third of Republicans think that scientists should "[t]ake an active role in public policy debates about scientific issues," as opposed to two-thirds of Democrats. Only 7 % of Democrats think that scientists have too much influence in public policy debates. One important question, of course, is whether laypersons who weigh in on scientific issues have informed opinions, and another is whether scientists who weigh in on issues outside their own fields have opinions that are more informed than anyone else's.

A science policy bulletin from the American Institute of Physics, Public Opinion Divided over Role of Scientists in Policymaking, by Lindsay McKenzie, synopsized the Pew article and stated,

Perceptions that scientists are poor communicators and feel superior to others “pain me to my core,” said Sudip Parikh, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, during [an] event discussing the survey results. “Humility is an absolute requirement for science communication,” said Parikh. “If you can’t be humbled about the fact that science is done by humans and we are all subject to all the fallibility and all the extraordinary talents that humans have, then you can’t relate.”

A Times article, Americans Have Regained Modest Trust in Scientists, Survey Finds, by Teddy Rosenbluth, incidentally, speculates,

Recent high-profile medical and scientific advancements — like the new gene therapy for sickle cell and ambitious space exploration missions — have done the most to rebuild confidence in scientific institutions, [Parikh] added.