Every Living Thing: book report

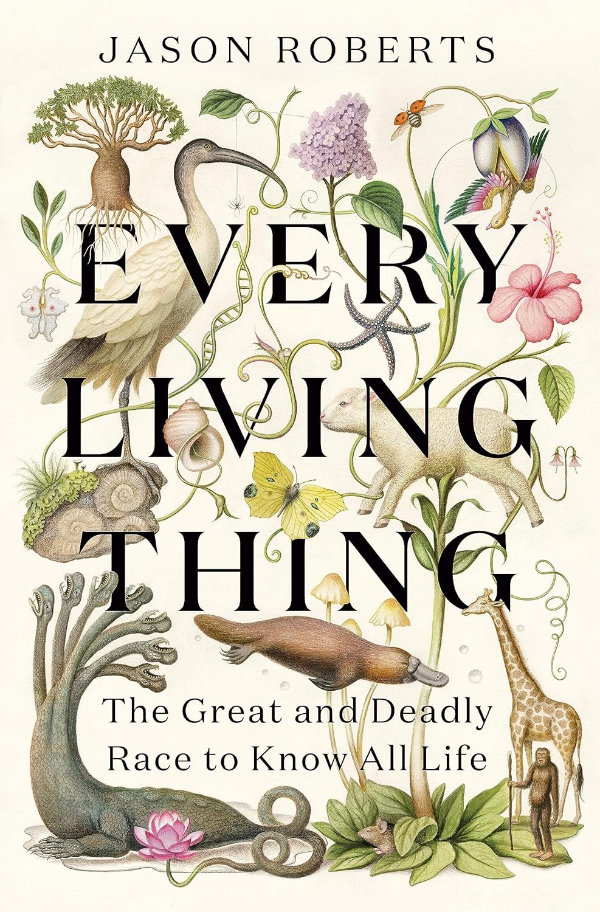

The book is Every Living Thing, The Great and Deadly Race to Know All Life, by Jason Roberts. It is sort of a double biography of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) and Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788), but it continues to follow their legacies well beyond their lifetimes to the present. I cannot recommend it more highly.

I do not know what impression Mr. Roberts intended, but if you thought Linnaeus was a young man on the make, something of a scoundrel who might say anything in the interests of self-promotion, you might not be too far from the truth. The hero of this book is not Linnaeus but rather his sometime rival, Buffon.

But let us deal with Linnaeus first. Linnaeus obtained a phony doctor’s degree from what we would now call a diploma mill. He anointed 14 (or 17 of what he called his “apostles” (!), sent them on long journeys from which many never returned, and completely abandoned one who returned with no specimens. He has been criticized for not allowing his daughters their educations, to a degree, says Roberts, that was extreme even for the time (but he supported his daughter Elisabeth in her interest in botany. She wrote a paper devoted to what is now known as the Elizabeth Linnaeus phenomenon). Linnaeus also believed in the fixity of species, not to mention some very bizarre creatures, but in that he was probably not alone.

Linnaeus developed a taxonomy that is largely in use today; that is a major accomplishment, to say the least. After defining and then apparently rejecting some ridiculous species within the genus Homo, he divided Homo sapiens into four subspecies: in essence, European, African, indigenous American, and Asian. Europeans, to Linnaeus, were governed by laws, whereas Africans were governed by whim, Americans by customs, and Asians by opinions. Roberts notes that “apologists have attempted to absolve Linnaeus of racism,” but he insists that claiming that Europeans alone were governed by laws is a clear statement of superiority. He cannot forgive Linnaeus, who stood by these characterizations for the rest of his life. I do not know whether Roberts is engaging in presentism, but I suspect not.

Linnaeus occasionally defined species on the basis of scant evidence and sometimes published reviews of his own work using a pseudonym. Roberts accuses him of drawing “unmoored conclusions” in “an act of ignorance masquerading as savantry.” Buffon was the real thing; he would have been called a scientist, but the first known use of the word was in 1834. Where Linnaeus required scant evidence, Buffon studied his “private menagerie” for years and concluded, in Roberts’s words, “The essence of species lay in reproduction, the ability of one generation to propagate another.” On the basis of what is essentially this definition, Buffon further concluded that there was only one human species, which “underwent diverse changes from the influence of the climate, food, mode of living, epidemical distempers, and the intermixture of individuals[.]” Charles Darwin, a century or so later, thought that Buffon’s theories were “laughably like mine.” Like Darwin, Buffon opposed slavery, and he did not care for the slave-owner Jefferson. Roberts does not discuss Linnaeus’s views on slavery.

Buffon ultimately published 35 volumes of his encyclopedia, Histoire naturelle. According to the author, he outsold Rousseau, Voltaire, and Montesquieu, and his work continued in print for over 150 years. Roberts says it is the longest nonfiction work written by a single author and rivals encyclopedias written by many authors.

Besides evolution, Buffon developed what Roberts calls “the first rough sketch of a working theory of reproduction,” which included an “internal matrix” that sort of resembles DNA. Where Linnaeus insisted on the fixity of species, Buffon studied fossil remains and concluded that some species had gone extinct and others had been born. Species, he thought, changed by adaptation to the environment, and later species were demarcated from their ancestors when they could no longer interbreed (cf. the modern biological species concept). He thought that related families may have a common ancestor and indeed that all life could be further traced to a yet earlier common ancestor. Buffon realized that these were dangerous thoughts in the mid-1700’s; he wrote to a friend, “One can slip ideas into a quarto volume which would cause a public outcry if they appeared in a pamphlet.” In consequence, he was very careful and penned a disclaimer any time he drew a conclusion that might offend the religious hierarchy.

Buffon also suggested that single-celled organisms may not all be animals or plants but rather “indeterminate species and in-between objects which we do not know where to place…” and suggested that living organisms might consist of building blocks now known as cells. On a less biological note, he opened an ironworks, which Roberts calls “a template for factories to come.” A gazebo that he had cast was the “first all-iron structure in Paris.” Its roof is a lattice shaped as a one-sheeted hyperboloid (a hyperboloid of revolution), which did not appear in architecture until the 20th century. According to Wikipedia, Buffon’s needle was the first solved problem in geometric probability.

Buffon deduced that the earth was much older than a few thousand years and divided its history into seven “epochs.” Apart from not knowing the duration of any epoch, he got their chronology about right. (In fact, he used cannonballs to estimate the rate of cooling of the earth and concluded that its age was around 75,000 years.) Roberts calls his work a deliberate provocation and an attack on the fixity of species. For his pains he was denounced by the Sorbonne and required to sign a retraction, which he promptly ignored.

Buffon speculated – very carefully – as to whether nonhuman animals had souls, for which transgression apparently Madame Pompadour smacked him in the face with a fan. He recognized, nearly 300 years ago, that humans could “despoil and impoverish” the earth by out-producing its capacity.

History was kinder to Linnaeus than to Buffon. Buffon’s star began to fade during the French Revolution, when the Société de Linné took advantage of the turmoil to promote Linnaeus and minimize Buffon. By the 1860’s in England, Buffon’s Natural History was sold in badly abridged, perhaps caricatured form alongside Aesop’s Fables. Shaw remembers as a child hearing Buffon called “Buffoon” and says that within 10 years he was forgotten. Perhaps this book will succeed in reviving enhancing his legacy.

Finally, I liked the writing very well and noticed only four editorial mistakes: seraphim for seraph, Camillia sinsesis for Camellia sinensis, counsel for consul, and Ernest Haeckel for Ernst Haeckel. Well, maybe one more: Rosalind Franklin arguably did not win a Nobel Prize because she had died before the prize was awarded.

Acknowledgment. Thanks to Ron Wittmann for discussing taxonomy and other topics with me. Deanna Young read a draft and offered several useful comments.