Do liberals, like conservatives, reject scientific facts?

I hate to begin a paper with, “Everybody knows”; it sort of buries your lead. Nevertheless: “Everybody knows” that conservatives are generally biased against the theory of evolution and all that it entails, and, especially, the scientific fact of anthropogenic climate change. Anyone who refuses to believe in descent with modification, the vast age of the earth, and climate change is definitively wrong. Indeed, the right wing is so wrong on climate change that the American Conservative magazine ran an article decrying the facts that climate change is real and that the obvious solutions are contrary to the conservative agenda. Indeed, the Pew Research Center reports that only about one-quarter of Republicans accept the reality of climate change, irrespective of education. Democrats’ acceptance of climate change, by contrast, increases with education.

Studies by Peter Ditto and by Anthony Washburn and Linda Skitka suggest that liberals and conservatives are about equally unwilling to listen to evidence that contradicts their beliefs and engage equally in motivated reasoning.

Do liberals, then, have similar biases, where you might be tempted to say that they were flatly wrong? That is harder to say. The science journalist Chris Mooney says no. The 2015 Pew Report, Americans, Politics, and Science Issues, shows declining support for building nuclear power plants with increasing identification as a liberal – even though, according to the Times, here, nuclear power is the only currently available technology that can generate electricity continuously at a large enough scale to combat climate change. Indeed, again according to the Pew Report, Republicans are closer to the position of a survey of AAAS members, 65 % of whom favor building nuclear power plants. The same is true of fracking; the more liberal, the more likely to oppose fracking. On the other hand, the Pew Report finds no significant differences of opinion between liberals and conservatives, or Democrats and Republicans regarding the safety of genetically modified foods.

Nuclear power plants and fracking have their drawbacks, fracking probably more so when it is deployed near homes and schools. We cannot say that someone who opposes nuclear power plants is definitively wrong in the way that someone who denies anthropogenic global warming is definitively wrong. Another area, which I admit is somewhat fraught, is the question of whether intelligence is heritable (or, more precisely, whether differences of intelligence may be inherited).

In fact, differences of intelligence are at least partly heritable. Robert Plomin of King’s College London explains in Scientific American that genes are thought to account for about half the differences of intelligence among different people. In an earlier article, Professor Plomin averred that the relevant genes had not (yet) been discovered; he was quoted out of context in The Guardian in an effort to claim that, because we have not found the genes, they must not exist. That article was later refuted in a follow-up article that described precisely how we know that intelligence is partly inherited. More recently, Professor Plomin and Sophie von Stumm state in a review paper that researchers have since discovered inherited genome sequence differences that account for approximately one-fifth of the total heritability of intelligence. (This review paper also includes a nice discussion of what is meant by intelligence and how it is measured.) An editorial in Nature noted that the heritability of intelligence is completely uncontroversial among geneticists and stated three reasons why it is controversial among the public: fear of determinism, fear of eugenics, and fear of racism. Steven Pinker in The Blank Slate employs similar arguments.

While I was obsessing with these articles (and others; see Bibliography), I was fortunate to receive a preprint of a paper by Emily Willoughby and her colleagues. Ms. Willoughby is a co-author and main illustrator of the anti-creationism book God’s Word or Human Reason? and is now pursuing a Ph.D. in behavioral genetics at the University of Minnesota. She illustrated an article for Panda’s Thumb here.

Ms. Willoughby’s paper concerns, among other things, “lay beliefs” about heredity. The paper includes an analysis of a survey which asked participants’ estimates of the relative contributions of genes and environment to 21 different human traits. The results, which included a suite of information including sex, age, number of children, education level, and political orientation, go a long way toward answering the question whether liberals are inclined to disbelieve the scientific fact that intelligence is a partly heritable trait. The British Psychology Society discussed Ms. Willoughby’s paper here, incidentally, and seemed most impressed by the finding that women with children were more accurate in their estimates than everybody else.

Ms. Willoughby and her colleagues surveyed several hundred US residents at least 18 years old. They were recruited by using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk); social-science data obtained using MTurk have been shown to be as reliable as data obtained using what they call “traditional methods.” Participants answered various questions gleaned from what I take to be standard sources. I read primarily the introduction, the figures and tables, and the conclusion, and mostly skimmed the rest of the paper. The main results that interested me are summarized in 4 sets of bar graphs from the Supplementary Material, which Ms. Willoughby very kindly provided me. The researchers used a statistical technique called exploratory factor analysis to group the patterns of responses into 4 sets of traits, which they named Physical, Psychiatric, Lifestyle, and Psychological traits. Interestingly, they did not arbitrarily group the data into those four sets; rather the four sets fell out of the analysis and represent the clusters of traits on which participants are likely to respond similarly, regardless of their political leanings. For example, a participant who judges a low heritability for one trait in the Psychological group is likely to also judge low estimates for the other traits in this group (and vice versa).

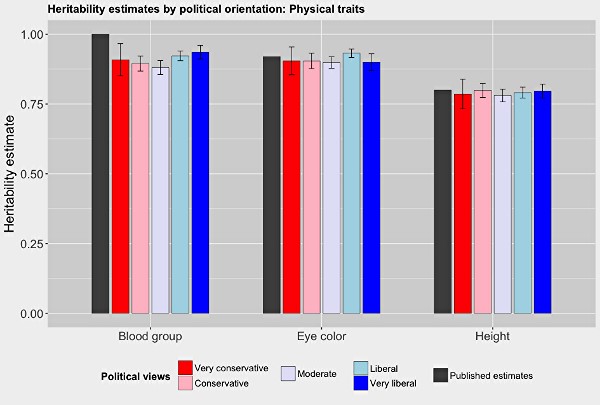

Figure 1 shows the accepted scientific values of the heritability of blood group, eye color, and height, and compares those values with estimates made by people with various political views. Liberals and conservatives on average provide approximately the same estimates, as we might expect for subjects that ought to be completely uncontroversial. These data thus act as a control for the rest of the measurement.

The error bars, which we will discuss below, represent the 95 % confidence interval </i>CI</i>, which corresponds approximately to ±2 standard deviations of the mean. (The confidence interval is an estimate of the precision; the true value of any measurement falls within the confidence interval with a probability of 95 %, provided that there are no sources of uncertainty besides random.) That the confidence intervals vary from group to group reflects variability within each group, as well as sample size, and does not necessarily imply significant difference among groups. For example, the very conservative group shows larger CI because the sample was smaller. Nevertheless, the fact that error bars in each cluster mostly overlap suggests that the measurement is very precise.

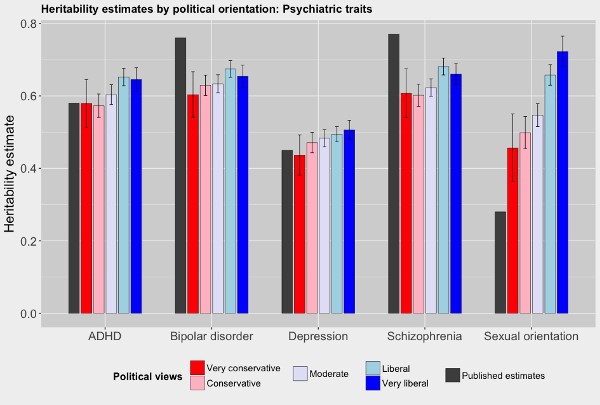

Figure 2 shows estimates of what the authors call psychiatric traits, again grouped according to political orientation. Interestingly, in all cases, liberals estimate the heritability of each psychiatric trait higher than conservatives, though not necessarily enough higher to be meaningful. While sexual orientation would not be normally grouped as a “psychiatric trait,” it is included in this category because the factor analysis indicated that participant responses clustered it along with the actual psychiatric traits surveyed. In other words, the variance in surveyed responses to the sexual orientation item was much more similar to the variance in ADHD, bipolar disorder, and so on than for any other trait or group of traits – regardless of political orientation. That said, liberals overestimate the heritability of sexual orientation substantially more than do conservatives. They are evidently more likely to assume that sexual orientation is innate, whereas published estimates suggest that less than one-third of its variance is actually heritable; even so, it still could be primarily biological.

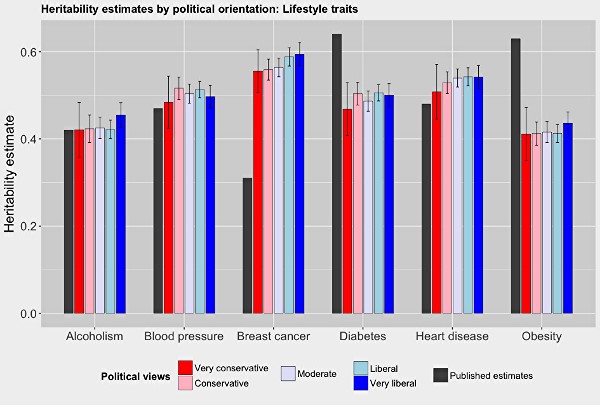

Figure 3 shows participants’ estimates of the heritability of what the researchers call “lifestyle traits.” Mostly, those are diseases, some of which may be associated with lifestyle choices. Nothing seems particularly noteworthy, except that liberals (and in particular “very-liberals”) mostly give higher estimates than everyone else. Overall, participants’ accuracy is not particularly good, with 2 serious underestimates and 1 serious overestimate. I will hazard the guess that people overestimate breast cancer because of the notoriety of the BRCA genes.

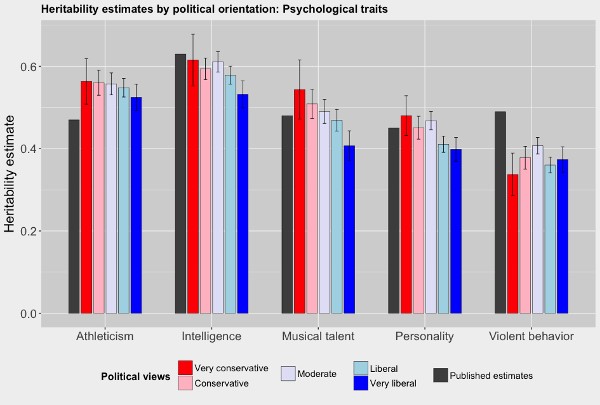

Figure 4 shows participants’ estimates of the heritability of what the authors call psychological traits. In particular, it appears that liberals, on average, underestimate the heritability of traits such as intelligence, musical talent, and personality. Very conservative participants estimate the heritability of intelligence measurably higher than do very liberal participants. Indeed, very conservative and moderate participants come particularly close to the published estimate. Even so, on average, liberals estimate that the heritability of intelligence is more than 50 %. Not all liberals deny that intelligence is heritable.

Interestingly, this result is not inconsistent with a survey of sociological theorists by Mark Horowitz and his colleagues. They found that approximately 80 % of those who responded to their survey found plausible the statement, “Although the environment affects the range of one’s intellectual development, some people are born genetically with more intellectual potential than others.” The remainder found it implausible or uncertain in roughly equal proportions.

Additionally, in Figures 2 and 3, the mean values generally increase from very liberal to very conservative. In Figure 4, they decrease from very liberal to very conservative. In some of the clusters, the increase or decrease is slight, and the error bars overlap. But the consistency from cluster to cluster suggests that the increase or decrease is real.

My main interest was whether liberals (wrongly) minimize the heritability of intelligence, so I looked closer at the intelligence cluster. Ms. Willoughby provided me with a spreadsheet that included the sample standard deviation SD of each political subgroup on each surveyed trait. The sample standard deviation is a measure of the spread of the data (not the uncertainty of the measurement). Using the data in the spreadsheet, I calculated the quantities M–2SD and M+2SD, where M is the mean value. These two numbers approximate the 95 % confidence interval of the sample. In principle, 95 % of the participants’ estimates of the heritability in each bar fall between these two limits; correspondingly, approximately 2.5 % of the estimates fall below the confidence interval and the same number above the confidence interval.

The confidence interval for very-conservatives ranges from 0.12 to 1.11, which we round down to 1, because that is the highest acceptable value. The confidence interval for very-liberals ranges from 0.09 to 0.97. Roughly speaking, only 2.5 % of very-liberals estimate heritability of intelligence to be less than 0.09 and 2.5 % of very-conservatives estimate it to be less than 0.12. The difference (0.09 and 0.12) is slight but could be significant near the tail of the distribution, so it is possible that more very-liberals estimate a very low value of heritability. A few percent of very-conservatives, on the other hand, must estimate the heritability as 1.

Conservatives, moderates, and liberals are not very different: 0.23 to 0.96, 0.20 to 1, 0.17 to 0.99, in that order, meaning that the lower bound of the confidence interval for those closer to the political center is higher than for those at either end. The upper bound of the confidence interval is about the same for all groups, meaning that approximately the same fraction of those groups estimated the heritability to be 1 or close to 1.

It appears that liberals (possibly as opposed to liberal columnists) underestimate the heritability of intelligence only slightly more than everyone else. But, in personal communication with me, Ms. Willoughby cautions against being overly optimistic:

It’s true that people across the political spectrum were a lot more accurate in their judgments than we were expecting. But if you look at the means across political groups for the different trait groupings, there are some patterns that are hard to ignore. It seems that conservatives are a lot more likely to believe that traits associated with success and achievement, like intelligence and musical ability, have a greater genetic component. Liberals, on the other hand, are more likely to think the same for traits that have been historically stigmatized, like psychiatric disorders and sexual orientation – which is probably why sexual orientation grouped so surprisingly with things like bipolar disorder and depression. So, overall accuracy notwithstanding, it looks like both ends of the political spectrum are allowing their particular moral inclinations to bias their interpretation of empirical questions about genes and environment. These findings are in line with published research by J. Haidt, J. Graham, and B. A. Nosek, among others, which suggests that moral judgments are a hallmark of the political split in the United States. Liberals tend to endorse moral foundations built around care, compassion, and reciprocity, while conservatives are equally observant of issues related to loyalty, authority, sanctity, and orderliness.

I think our data do show that people on the left – especially the far left – are more likely to underestimate the heritability of intelligence and other psychological traits than conservatives are, even if very few of them are outright denying it. I think we should take two main things from these findings: First, as a motivation to examine our own motivations and biases when forming opinions about nature and nurture, and to think about where these biases come from. And second, as evidence that neither end of the political spectrum is free of fault or free of praise in the objectivity of their assumptions. The overall correlation between the published estimates and the mean estimates for all of the traits came out to 0.77, which is very high for this kind of research. Until we can all make progress in correcting our bias, we should acknowledge that sometimes a diversity of viewpoint really is a benefit to accurate understandings.

I made a sardonic comment earlier about liberal columnists, such as the author of this column, which I mentioned earlier. Importantly, the article was later refuted in the same newspaper. The evidence in Ms. Willoughby’s paper suggests that liberals are not as strongly opposed as the columnist. They are not monolithic in their opposition to modern science. Vaccination denial and fear of genetically modified foods cut across the liberal-conservative spectrum. Nuclear power (which, incidentally, I support) is not cut and dried; opposition to nuclear power, while shrill, is not wholly irrational. Neither is opposition to fracking. The evidence from Ms. Willoughby’s paper suggests that a small percentage of liberals may flatly deny the heritability of intelligence and others underestimate it. It is important that we refute such denials. But, except perhaps for the far left, liberals’ responses are not so greatly different from everyone else’s.

To answer the question posed in the title, yes, liberals reject scientific facts. But when they do so, as with fracking, vaccination, and GMO’s, their opinions are not so greatly different from those of the general public. Liberals on the whole do not have vast lacunae, similar to conservatives’ rejection of evolution, the antiquity of the earth, and climate change, where they – almost exclusively – reject some scientific fact. Do liberals, like conservatives, reject scientific facts? Yes, but they do not as a group single out whole areas of scientific knowledge and reject them. So no, liberals do not reject scientific facts in the way that conservatives do.

Acknowledgements.

Profuse thanks to Emily Willoughby for supplying the draft of her paper, for iterating with me once or twice regarding the figures, and for reading what sometimes seemed to be countless revisions.

Bibliography.

Addison del Maestro, “Too good a problem: Liberal politics foster climate skepticism,” The American Conservative, 30 January 2017; http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/too-good-a-problem/

Dana Nuccitelli, “Pew survey: Republicans are rejecting reality on climate change,” The Guardian, 6 October 2016; https://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2016/oct/06/pew-survey-republicans-are-rejecting-reality-on-climate-change.

Peter H. Ditto, et al., “At least bias is bipartisan: A meta-analytic comparison of partisan bias in liberals and conservatives,” SSRN (2017); http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2952510.

Anthony N. Washburn and Linda J. Skitka, “Science denial across the political divide: Liberals and conservatives are similarly motivated to deny attitude inconsistent science,” Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14 September 2017; DOI: 10.1177/1948550617731500.

Chris Mooney, “Stop pretending that liberals are just as antiscience as conservatives,” Mother Jones, 11 September 2014; https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2014/09/left-science-gmo-vaccines/.

Pew Research Center, Americans, Politics and Science Issues, 1 July 2015; http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2015/07/2015-07-01_science-and-politics_FINAL-1.pdf.

Eduardo Porter, “Are liberals impairing our ability to combat climate change?” The New York Times, 19 April 2016; https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/20/business/economy/liberal-biases-too-may-block-progress-on-climate-change.html.

Robert Plomin, “Is intelligence hereditary?” Scientific American, n.d.; https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/is-intelligence-hereditary/.

Oliver James, “How to raise a brilliant child without screwing them up,” The Guardian, 27 February 2016; https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/feb/27/how-to-raise-a-brilliant-child-without-screwing-them-up.

Marcus Munafo, “Genetic denialism is unhelpful - genes play a role in who we are,” The Guardian, 4 March 2016; https://www.theguardian.com/science/sifting-the-evidence/2016/mar/04/genetic-denialism-is-unhelpful-genes-play-a-role-in-who-we-are.

Robert Plomin and Sophie von Stumm, “The new genetics of intelligence,” Nature Reviews Genetics 19, 148–159 (2018); https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg.2017.104.

Anonymous, “Intelligence research should not be held back by its past,” Nature, 545, 385–386 (25 May 2017); https://www.nature.com/news/intelligence-research-should-not-be-held-back-by-its-past-1.22021.

Steven Pinker, “The fear of inequality,” Chapter 8 of The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, Penguin, 2016; https://www.amazon.com/dp/B000QCTNIM.

E. A. Willoughby, A. C. Love, M. McGue, J. Quigley, and J. J. Lee, “Free will, determinism, and intuitive judgments about the heritability of behavior,” OSF preprint (2018); https://osf.io/ezg2j/. Supplementary material here: https://osf.io/8fyau/.

Christian Jarrett, “Nature vs nurture: Mothers with multiple children have an intuitive grasp of behavioural genetics,” British Psychological Society Research Digest, 19 February 2018; https://digest.bps.org.uk/2018/02/19/nature-vs-nurture-mothers-with-multiple-children-have-an-intuitive-grasp-of-behavioural-genetics/.

M. Buhrmester, T. Kwang, and S. D. Gosling, “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data?” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6(1), 3–5 (2011); http://datacolada.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Burhmester-Kwang-Gosling-2011.pdf.

Mark Horowitz, William Yaworski, and Kenneth Kickham, “Whither the blank slate? A report on the reception of evolutionary biological ideas among sociological theorists,” Sociological Spectrum, 34, 489-509 (2014); https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02732173.2014.947451. Full disclosure: I read primarily (but not exclusively) the Introduction and Discussion sections of this paper, and some of the Tables.

J. Graham, J. Haidt, and B. A. Nosek, “Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96(5), 1029–1046 (2009); http://www-bcf.usc.edu/~jessegra/papers/GrahamHaidtNosek.2009.Moral%20foundations%20of%20liberals%20and%20conservatives.JPSP.pdf.

Additional bibliography.

J. Frimer, L. J. Skitka, and M. Motyl, “Liberals and conservatives are similarly motivated to avoid exposure to one another’s opinions,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 1-12 (2017); http://motyl.people.uic.edu/FSM2017.pdf.

Geoffrey D. Munro and Peter H. Ditto, “Biased assimilation, attitude polarization, and affect in reactions to stereotype-relevant scientific information,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 636-652 (1997); http://psp.sagepub.com/content/23/6/636.

Maria Konnikova, “I don’t want to be right,” The New Yorker, 16 May, 2014; http://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/i-dont-want-to-be-right.

Chris Mooney, “The science of why we don’t believe science,” Mother Jones, March, 2011; http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2011/03/denial-science-chris-mooney.

Joe Keohane, “How facts backfire: Researchers discover a surprising threat to democracy: our brains,” Boston Globe, 11 July 2010; http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2010/07/11/how_facts_backfire/.

Steven Pinker, “Groups and genes,” The New Republic, 25 June 2006; https://newrepublic.com/article/77727/groups-and-genes.

Michael Shermer, “Science denial versus science pleasure,” Scientific American, November, 2017; https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/science-denial-versus-science-pleasure/.